Features

Aria of Sorrow: The Symphony of the Night Sequel Castlevania Needed

Aria Of Sorrow Retrospective

Castlevania’s run from 1986 to 1997 is downright legendary. While there are a few duds sprinkled throughout the series’ first decade (Simon’s Quest, The Adventure, Dracula X), this is the same franchise that produced Super Castlevania IV, Rondo of Blood, and Bloodlines over the course of three years– three of the greatest action platformers of all time. 1997 saw Castlevania reach what was arguably its highest point when, unprompted and with no real need to do so, Symphony of the Night pulled off such an expert reinvention that it ended up creating a new genre altogether. With 11 years of goodwill to bank on, Castlevania’s future would never look as bright again– and unfortunately for good reason.

Following the revolutionary success of Symphony of the Night, Castlevania almost immediately fumbled as a franchise. 1997 closed out not with Symphony of the Night, but the ferociously underwhelming Legends, a Game Boy title that took a cleaver to the franchise’s lore and massacred it. The Nintendo 64 would see the release of Castlevania in 1999, arguably the worst transition from 2D to 3D on the N64, followed by a moderately improved but still mediocre re-release that same year, Legacy of Darkness. By 2000, Castlevania had entered the 21st Century at its lowest point, with Symphony of the Night silently in the background, untouched.

As if to signal a return to form, however, 2001 saw Konami release two fairly noteworthy titles: Circle of the Moon for the Game Boy Advance and Castlevania Chronicles for the PlayStation. Where the latter was a remake of the first game, Circle of the Moon marked the series’ first attempt at producing a mechanical sequel to Symphony of the Night. Utilizing the Metroidvania format SotN popularised, Circle of the Moon was met with near-universal acclaim at release due to its difficulty curve, tight platforming, and a gameplay loop catered towards old school fans.

Which alone is enough to make Circle of the Moon less a Symphony sequel, and more a Castlevania stuck between the Classicvania and Metroidvania model. It’s a good title for what it is, but Circle of the Moon is so fundamentally different from Symphony of the Night that series producer Koji Igarashi overcorrected when re-taking the reins for 2002’s Harmony of Dissonance, a game that– while good– shamelessly apes everything it can from SotN in an attempt to win over audiences. Juste Belmont looks like Alucard, there’s a variation of the Inverted Castle twist, and the game was designed with the explicit purpose of capitalizing on Symphony of the Night.

To Konami’s credit, the series had regained its legitimacy between both Circle of the Moon and Harmony of Dissonance, but neither game captured Symphony’s inventiveness. CotM deserves some slack for generally doing its own thing and remaining the most unique Metroidvania in the series to date, but Harmony of Dissonance plays itself too safe, ultimately just winding up a worse version of Symphony of the Night. Not just that, there was the matter of the series’ story. 19 games in and past the turn of the century, the story couldn’t stay in the background anymore. Legends, Legacy of Darkness, Circle of the Moon, and Harmony of Dissonance all tried to tell a compelling story and they all faltered along the way.

Castlevania wasn’t in need of reinvention in 2003, but refinement. The series was good, not great, and every new release was only shining a spotlight on how good Symphony of the Night was, not on how its successors were following it up. It only makes sense, though. How is a franchise meant to follow-up a game like Symphony of the Night? How can Castlevania even be discussed anymore without mention of what is unquestionably one of the greatest video games of all time? It seemed as though the franchise was suffering for no reason at all, but there’s actually a fairly simple answer as to why the series struggled between 1997 and 2003: the lack of the dream team.

Castlevania often shuffled around its development teams, but Symphony of the Night managed to land a team that in retrospect is on par with the likes of Chrono Trigger’s legendary development team. Alongside Koji Igarashi– who at the time was assistant director, a programmer, and the scenario writer– Michiru Yamane composed her second soundtrack for the series following Bloodlines, and Ayami Kojima made her debut as a character designer, solidifying the franchise’s gothic aesthetic for good. Unfortunately, the three wouldn’t all intersect again for some time, leaving the Castlevania games to come without the essential players who made Symphony of the Night what it was.

Igarashi and Kojima would work together again on both Chronicles & Harmony of Dissonance, but Yamane’s other work kept her from Castlevania between 1997 & 2003, and none of them would work on Legends, Legacy of Darkness, or Circle of the Moon. The nature of the industry meant there was no guarantee the three would work on the same project again, but now Castlevania’s lead producer, Koji Igarashi had pull to hire Yamane as the lead composer of his next Castlevania game. Ready to address Harmony of Dissonance’s criticisms, Koji Igarashi set the stage for the game that would breathe new life into Castlevania– Aria of Sorrow.

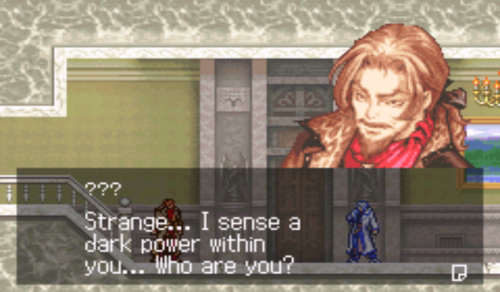

Instead of calling attention to itself as a successor to Symphony of the Night– something the game admittedly could’ve gotten away with given its production team– Aria of Sorrow does everything it can to assert its individuality asap. Soma Cruz has seemingly no connection to the Belmonts or Dracula, Dracula’s Castle is now inside of an eclipse, and the timeline is no longer rooted in history with the story set in 2035. This is all information conveyed in the opening title crawl, but less than a full minute into gameplay and audiences are already introduced to the Soul mechanic, a system that allows Soma to absorb enemy Souls in order to use their techniques. From there, it’s on the onus of the player to explore.

For such an all-encompassing opening, Aria actually kicks off with little fanfare. Symphony of the Night, Circle of the Moon, and Harmony of Dissonance all open with spectacle, but Aria of Sorrow keeps itself subdued, understanding that while Symphony’s spectacle was indeed an important part of its identity, it’s the gameplay that ultimately won audiences over. Aria of Sorrow wastes no time in presenting its defining Soul mechanic, making it the very first concept players will fully understand: kill enemies to get Souls, use Souls to kill enemies. It’s a simple gameplay loop, but it keeps Aria of Sorrow’s blood pumping long after the credits roll.

With Soul drops determined by RNG, no two playthroughs will be the same. Such an approach might bother those looking to 100% the game, but it’s exactly this reason why Aria of Sorrow remains so enjoyable to replay. With over 100 Souls available for use, Soma can accomplish far more than any other Castlevania protagonist. Soma can equip three Souls in total at any given moment: one Bullet Soul, Aria’s sub-weapons; one Guardian Soul, skills that can be triggered with R; and one Enchanted Soul, passive abilities that don’t need to be activated. Soma also has access to Ability Souls, inherent techniques that he can activate & deactivate ala Alucard’s skills from Symphony.

While the Soul system is more than enough to freshen up the series’ core combat, Aria of Sorrow ditches whips and goes back to the Alucard method of collecting multiple different weapons. Between Souls and Soma’s generous arsenal of weaponry, all play styles are accommodated. Normal Mode is also more forgiving than usual, with Hard Mode better designed for series veterans. This isn’t ideal since most will play Normal and miss out on Hard Mode altogether, but it’s an approach that– in theory– does accommodate fans old and new alike. Aria of Sorrow has an almost overwhelming amount of content, but that’s exactly why it’s so accessible. There’s a weapon, Soul, or difficulty for everyone.

Engaging combat mechanics means very little without the proper level design, however. Where Harmony of Dissonance comfortably followed a “bigger is better” mentality to its castle’s design, Aria of Sorrow shows a considerable amount of restraint. There is no second castle to unlock– what you see is what you get. Areas are more interconnected than usual, ensuring that fewer areas end up in dead ends, and the castle’s settings are visually grounded for the most part. Aria indulges in chaotic visuals and level design for the final area, but the castle leading up to the finale is unusually comprehensible. As far as navigation goes, this is the best castle in the series.

Of course, the high-quality castle only makes sense when one remembers that it’s Ayami Kojima’s art style that serves as Aria of Sorrow’s base. Moody and gothic, Kojima’s self-taught style has an earthy quality that easily tips into the fantastical, an aesthetic that fits Castlevania perfectly. Michiru Yamane’s score seemingly builds off of Kojima’s art, following the lead with less catchy and more atmospheric tracks on a whole. This doesn’t mean Aria of Sorrow isn’t bursting with amazing songs– one only needs to listen to Heart of Fire to understand that– rather, it’s Aria’s way of keeping a mature, sorrowful tone throughout.

And Aria of Sorrow is indeed more mature than previous Castlevania titles when it comes to story. Where both Circle of the Moon and Harmony of Dissonance played their stories straight, Aria of Sorrow features a decent amount of subtext to bolster its already incredibly intriguing plot. Aria doesn’t just take place in the future, it takes place in a future where Dracula has been killed for good. No Dracula means that a new villain can rise up in the form of Graham Jones, and while he’s not that compelling, he ends up representing everything Dracula claims to despise in humanity. Graham is a hateful coward who thinks too highly of himself, and too little of others. A miserable little pile of secrets.

That said, while it’s always beneficial to keep characters who fill similar roles antithetical to one another, Graham’s personality is more layered than that. He may be the main antagonist, but he’s no Dracula. Literally. The main plot of Aria of Sorrow concerns itself with who Dracula has reincarnated into. It’s obviously Soma, a fact the series no longer tries to hide, but Aria of Sorrow very cleverly gets around this by doubling down on Graham’s evilness. He’s blatantly evil from his first interaction with Soma, but that’s exactly what keeps players from guessing the Dracula twist their first playthrough.

Soma being Dracula is the cherry on top of Aria of Sorrow, that last little detail that makes everything just right– not just in the game, but in the context of the series. Fast-forwarding far into the future, Aria of Sorrow establishes Dracula’s demise, a grand battle that took place in 1999, and the last Belmont– Julius– the man who killed Dracula for good, but lost his memory in the process. Aria doesn’t hold any punches when it comes to Soma either, making him succumb before the end of the game and even featuring an alternate ending where he embraces his demonic powers, leaving Julius to kill Dracula yet again.

Aria of Sorrow goes beyond wanting to replicate the greats and instead chooses to be great in its own right.

Although Soma has a clear love interest in Mina Hakuba, it’s the relationship between Soma and Julius that ties the story together. Aria is just as much a character study of Dracula through Soma as it is a celebration of the ultimate struggle between the Belmont clan and the Count. The roles have been flipped this time around, with Julius serving as the penultimate battle in one of the best (& hardest) boss fights in the franchise. As he’s not the main character, Julius is also allowed greater depth than the average Belmont. When he appears, it’s because the story calls for it and his scenes are never wasted.

They’re always used as a means to either flesh out the game’s backstory, or build-up to the confrontation between Soma and Julius. The two build a slight bond over the course of the game, one that turns into genuine respect by the time the two men are fighting to the death. It’s easy to overlook the substance in Julius’ interactions since he’s only in six scenes (including the bad ending), but they all slowly chip away at the man underneath– his history, his connection to Dracula, and what it means to be a Belmont. Which in itself is important, as it gives audiences an opportunity to see a Belmont in his element from not only an outsider’s perspective, but Dracula’s.

Soma’s relationship with Julius may be what best contextualizes Aria of Sorrow’s role in the franchise, but this isn’t to say that the supporting players don’t contribute. Hammer and Yoko Belnades are both on the flat side, but Mina and Genya Arikado do some heavy narrative lifting. Mina evokes images of Dracula’s wife, Lisa, who was first introduced in Symphony of the Night. Their dialogue shows how deeply they care for one another, and Soma’s Dracula-related insecurities end up tainting their dynamic at the end of the game, cutting Soma off from his only source of genuine affection and love. Not just that, Mina proves that Dracula could have adjusted to a normal life had mankind not killed Lisa.

Then there’s Genya Arikado, a man so blatantly Alucard that the word “Alucard” doesn’t need to appear in the script a single time for fans to make the connection– which it doesn’t. Aria of Sorrow features the main character from Symphony of the Night in an incredibly important and relevant capacity, and he neither looks like he did in Symphony of the Night or directly acknowledges his identity. Frankly, it’s the only tasteful way to use Alucard in a post-Symphony of the Night context. His character has evolved with time, and seeing him in a supportive capacity only makes sense given the events of his own game. His presence helps draw in a sense of finality alongside Mina and Julius.

These three characters thematically represent the main fixtures of Dracula’s life: Mina, the love that ties Dracula to humanity; Genya, the son who in spite of his father’s evil, loves him enough to ensure he can truly rest; and Julius, the final descendant of the Belmont clan and perhaps the strongest man alive. At the center of it all is Soma Cruz, the reincarnation of Dracula. Aria of Sorrow feels like the end of everything Castlevania represents. More games would follow, and Aria would even see a direct sequel in Dawn, but what makes Aria such a worthy successor to Symphony of the Night is that it wasn’t afraid to do something new and bold with Castlevania. Most of this boldness stems from the gameplay, but the story presents itself as a thematic end for Castlevania if nothing else. Dracula and the Belmonts may finally put their feud to rest.

Aria of Sorrow might not have had the same cultural impact of Symphony of the Night, but it’s exemplary of Castlevania at its best.

Or not. As previously mentioned, Aria of Sorrow features an ending where Soma goes full-Dracula. It’s morbid and cuts off right before Julius begins his fight with the dark lord, but it only makes sense. Aria doesn’t shy away from Dracula’s nastier aspects, and that means allowing Soma to be corrupted. Castlevania was always about the eternal struggle between Dracula and the Belmonts, so it’s only fair an ending offers a scenario where the cycle simply repeats. Regardless of which ending players find most appropriate, Michiru Yamane’s use of Bloody Tears in the track Epilogue makes one thing clear: Aria marks a new chapter for Castlevania.

When all is said and done, Aria of Sorrow doesn’t even feel like a sequel to Symphony of the Night. Aria goes beyond wanting to replicate the greats and instead chooses to be great in its own right. The end product is the end result of the series living in Symphony’s shadow for years. Koji Igarashi went beyond parroting himself, and instead entered production prepared to take Castlevania to the next level with a tried and true team. But even in sharing the same core members as Symphony, Aria never feels like anything but its own distinct game– a mature goodbye to Count Dracula, the Belmont legacy, and everything that happened in between. Aria of Sorrow might not have had the same cultural impact of Symphony of the Night, but it’s exemplary of Castlevania at its best.

-

Features4 weeks ago

Features4 weeks agoGet Ready: A Top Isekai Anime from the 2020s Is Headed to Hulu!

-

Features4 weeks ago

Features4 weeks agoSocial Gaming Venues and the Gamification of Leisure – A New Era of Play

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks agoSolo Leveling Snubbed?! You Won’t Believe Who Won First at the 2025 Crunchyroll Anime Awards!

-

Culture3 weeks ago

Culture3 weeks agoThe Global Language of Football: Building Community Beyond Borders

-

Technology4 weeks ago

Technology4 weeks agoIs Google Binning Its Google Play Games App?

-

Technology4 weeks ago

Technology4 weeks agoHow to Download Documents from Scribd

-

Guides4 weeks ago

Guides4 weeks agoBoosting and WoW Gold: Why Prestige and Efficiency Drive the Modern MMO Player

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks agoGamification and Productivity: What Games Can Teach SaaS Tools

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks agoFarewell to a Beloved 13-Year-Old Isekai Anime That Brought Us Endless Laughter

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoThis Upcoming Romance Anime Might Just Break the Internet; Trailer Just Dropped!

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks agoWait, What?! Tom & Jerry Just Turned Into an Anime and It’s Glorious!

-

Culture2 weeks ago

Culture2 weeks agoIs the Gaming Industry Killing Gaming Parties?

Mika

May 2, 2020 at 2:45 am

Simon’s quest was great. Aria of sorrow must have been drowned out because harmony was the last that carried a voice. And now Bloodstained clearly carries the torch.