Features

Harmony of Dissonance: A Castlevania Contradiction in Terms

Following the release of Castlevania: Circle of the Moon, series producer Koji Igarashi began development on Harmony of Dissonance intending to replicate his success with Symphony of the Night. While Circle of the Moon received high praise critically, Igarashi was less kind to the game in interviews leading up to Harmony’s release and specifically wanted to remedy CotM’s flaws in HoD. Igarashi’s criticisms of Circle touched on protagonist Nathan Graves’ sluggish controls, the dark color palette that could be barely seen on launch GBAs, and tonal inconsistencies with the rest of the franchise. Circle of the Moon was produced without Koji Igarashi’s involvement, which likely gave his comments at the time even more weight. This was an industry veteran criticizing an entry in his franchise while hyping up the second coming of one of the greatest games ever made.

The fact of the matter is that Harmony of Dissonance doesn’t warrant such hype nor is it a better Castlevania than Circle of the Moon: just different. Where Circle of the Moon embraced classic franchise conventions too closely, Harmony of Dissonance nests itself in Symphony of the Night’s shadow without shame. The end result is very reminiscent of SotN, but hardly comparable in quality. What’s especially a pity is that Igarashi did succeed in overcoming CotM’s flaws through HoD, only for Symphony to distort Harmony’s identity. What’s otherwise one of the most stylish and mechanically polished games in the series can’t help but be derivative. While that doesn’t make for a bad experience overall, it does undermine Harmony of Dissonance’s greater qualities.

One of the biggest issues with Circle of the Moon was its art direction. While CotM emulates and looks perfectly fine on modern hardware, the original Game Boy Advance’s screen struggled to clearly display darker visuals. Circle’s aesthetic coupled with the GBA’s hardware limitations led to a game that could only be played with the correct lighting. Harmony’s castle is noticeably much brighter, using a wider range of colors than usual for Castlevania. The color palette can almost be garish at times, but there’s a vibrancy evocative of the NES trilogy’s eclectic coloration. Harmony of Dissonance also features a bright blue border around Juste Belmont’s sprite, which (while jarring at first) helps him stand out against the busy art direction.

Beyond just being easier to see on an original GBA, Harmony of Dissonance’s graphics are quite ambitious for a handheld game. It’s easy to take for granted just how much is happening on-screen at any given time, from background details to enemy & player animations. Thunder flashes through the windows; clouds move across the sky; fog sets in over the castle’s seedier sections, and an abundance of tilesets helps to give even the smallest areas personality. Since sprites are larger than they were in Circle of the Moon, they’re afforded greater detail that lends the game a high level of visual polish where models can discernibly have multiple joints or even rotate in a way that wasn’t possible in CotM.

It’s worth keeping in mind that these graphical flourishes do come up at the price of sound quality. According to Koji Igarashi, Harmony of Dissonance had to “sacrifice the music” in benefit of the graphics. As a result, Harmony’s score is reflective of an 8-bit title and considerably more chiptune than its GBA brethren. The soundtrack is an acquired taste that can sound like whiplash coming off of Circle of the Moon, which featured several strong remixes of classic Castlevania tunes. None of this is to say that HoD’s soundtrack is actually bad, however. Limitations often bolster art and Harmony of Dissonance embraces a unique musical identity to get around the GBA’s technical faults.

A lack of Castlevania staples and the sound quality means Harmony of Dissonance’s soundtrack won’t appeal to everyone, but the actual compositions are superb. “Offense and Defense” is an almost ethereal track that clashes powerful melodies against each other into one of HoD’s most dynamic songs. “To the Heart of the Devil’s Castle” is the most action-packed piece of music in the game, using chiptune as a strength. “Prologue” is a haunting aggressive song that’s as jarring as it is unnerving. “Old Enemy” is one of the most chaotic and unique Dracula themes in the franchise, creating auditory mania out of technical limitations. Juste’s main theme, “Successor of Fate,” has the musical stylings of an NES track, but carries itself with an elegance that slowly builds into a sophisticated song christening players’ journey.

Juste himself is an interesting main character, both in terms of characterization and control. Design-wise, Juste lifts heavily from both Richter Belmont and Alucard’s redesigns, arguably Castlevania’s most popular main characters. Juste’s overall outfit comes off like a recolor of Richter’s with only minimal changes made to the coat, and his pale white hair screams “Son of Dracula” more than it does “Son of Belmont.” As far as personality goes, Juste feels like the love child of both protagonists as well, sharing Richter’s warmth for others and Alucard’s ironclad sense of justice. Juste isn’t without his own eccentricities, however, making him more than just an amalgamation of his predecessors.

Juste happens to be the first Belmont to be an interior decorator. Players can find an unfurnished room inside of Dracula’s Castle which Juste vows to spruce up. There are several pieces of furniture scattered around the castle, all of which come together to turn a tasteless room into a museum of your trophies. Collecting every piece of furniture even changes the ending so that Juste’s love interest, Lydie, is snuggling up close to him before the credits roll. It’s a minor detail in the grand scheme of things, but one that helps give both Juste and Harmony of Dissonance personality.

Control-wise, Juste is far more fluid than Nathan Graves – and every other Belmont, for that matter. Juste lacks the classic Belmont strut and runs like his ancestors never could. Not only does Juste inherit Alucard’s backdash from Symphony of the Night, he has a front dash that allows dodging to play a more reflexive gameplay role. Dashing quickly becomes second nature, especially since Juste can dodge right out of a whip strike (no longer forcing players to commit to their attacks). The Vampire Killer is Juste’s only weapon, but it can be augmented with elemental attributes and upgrades that reference the previous games.

Not just that, Juste can actually use magic on account of his Belnades bloodline (a fact every Belmont shares, but one only Juste can seemingly take advantage of). Different Spell Books can be paired with different Sub-Weapons to completely change their effect – in a way mirroring Circle of the Moon’s Dual Set-Up System (DSS). Axe/Fire summons dual pillars of flame that encircle Juste’s body. Fist/Ice allows players to do a dash jump in mid-air, letting you nab some useful items early. Cross/Bolt acts like a rotating Grand Cross (one of Richter’s Item Crashes). Bible/Wind spawns a rotating shield that repeatedly deals damage to any nearby enemies and fades on a timer, not contact. And the Summon Tome spawns different familiars depending on your equipped Sub-Weapon.

Juste’s controls avoid all of the stiffness present in Circle of the Moon, but at the expense of making combat far too easy. Juste is so agile that he can comfortably dodge most enemy attacks right before they land. This is in stark contrast to how Castlevania handles positioning. Being able to break a whip attack also goes a long way in softening the curve, removing an important layer of challenge (and complexity) to combat. It certainly doesn’t help that magic is ferociously overpowered. Spell Fusion drains MP, not Hearts, which already recharges automatically. Since bosses are almost always in close vicinity to save points, players are all but guaranteed to start all major fights with near-max MP. Savvy players can abuse magic to circumvent HoD’s hardest challenges altogether.

Running out of MP isn’t even damning since Sub-Weapons consume Hearts with no Spell Books equipped. If you run out of magic, just remove the Book and start throwing out Sub-Weapons. Harmony of Dissonance might very well have the easiest bosses in the series for this exact reason. Bosses aren’t inherently easy by design, but HoD stacks so much in Juste’s favor that you’ll only ever die if you’re careless. Similarly, players can hold onto 99 of each item instead of just 9, making it far too easy to horde healing items. The shop returns from SotN, allowing players to buy Potions for cheap, and in-game drops are much more generous than they were in Circle of the Moon, along with equipment once again being strewn about the castle to find.

Overall, Harmony of Dissonance is pitifully easy. The core combat is engaging but never challenging. Even at its hardest, HoD doesn’t push players to learn enemy patterns or master the controls. That said, Harmony does not hold back when it comes to level design, offering one of the most obtuse castles in the series to navigate. While there are more shortcuts than in Circle of the Moon, Harmony’s castle routinely bottlenecks players through the same few areas just to make a sliver of progress. The level design doesn’t direct Juste naturally, requiring thorough investigation or refined observational skills. You’re expected to remember stage details for hours at a time. The game’s pacing also means you’ll often fully explore rooms that you can’t do anything in yet, meaning you can’t rely on unfilled spaces on the map to guide you come the late game.

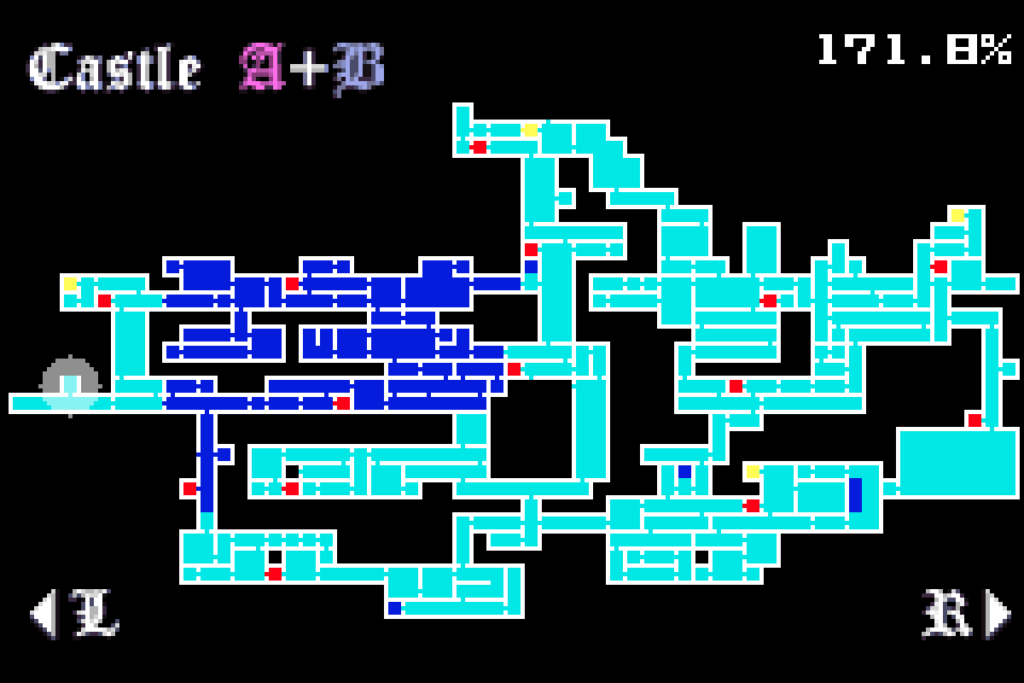

Forgetting where you’ve been or not knowing where to go next can feel like a punishment in and of itself. Navigation is made all the more confusing by Harmony of Dissonance’s perplexing dual castles. Rather than ripping off Symphony of the Night’s plot twist wholesale, Harmony inverts it. Instead of running into an Inverted Castle around the halfway point, Death explains to Juste that he’s been hopping between two separate castles roughly two-thirds of the way in. HoD features two parallel castles identical in structure, but not in item or enemy layout. All major areas repeat twice and the overall map is designed around the relationship between these two castles.

Players will actively explore both castles from the moment they find their first warp point. Navigation is slow-paced, and you’ll be methodically chipping away at both maps. It takes a while for HoD’s castle to open up and start embracing its shortcuts. More often than not, an early gate check will just lead to another gate right away. Even knowing exactly where to go doesn’t mitigate backtracking since so much of each castle is just fragmented. The early warp points bring players to sections of the castles that are more or less landlocked, with the larger teleporters rotating between each other (and allowing you to change castles on the spot). Regardless, exploration remains consistently limited up until you unlock every major ability. Only then does Harmony’s castle feel truly fulfilling to explore. Or at least it would without so much backtracking.

The problem with the dual castles system isn’t the fact each area is reused twice, but the sheer magnitude of backtracking that overshadows this distinction. You end up running through each area so many times that it becomes sincerely difficult to appreciate the discrepancies between both castles. The very concept of exploring two near-identical castles is less meaningful when backtracking is already forcing you to revisit key locations on the regular. If Harmony’s castle featured a more cohesive level design that made better use of branching paths or shortcuts, the novelty of exploring parallel castles over the course of one adventure wouldn’t feel so diluted by the mid-game. As is, Castles A + B comes off like a neutered and poorly paced variation of Symphony’s Inverted Castle.

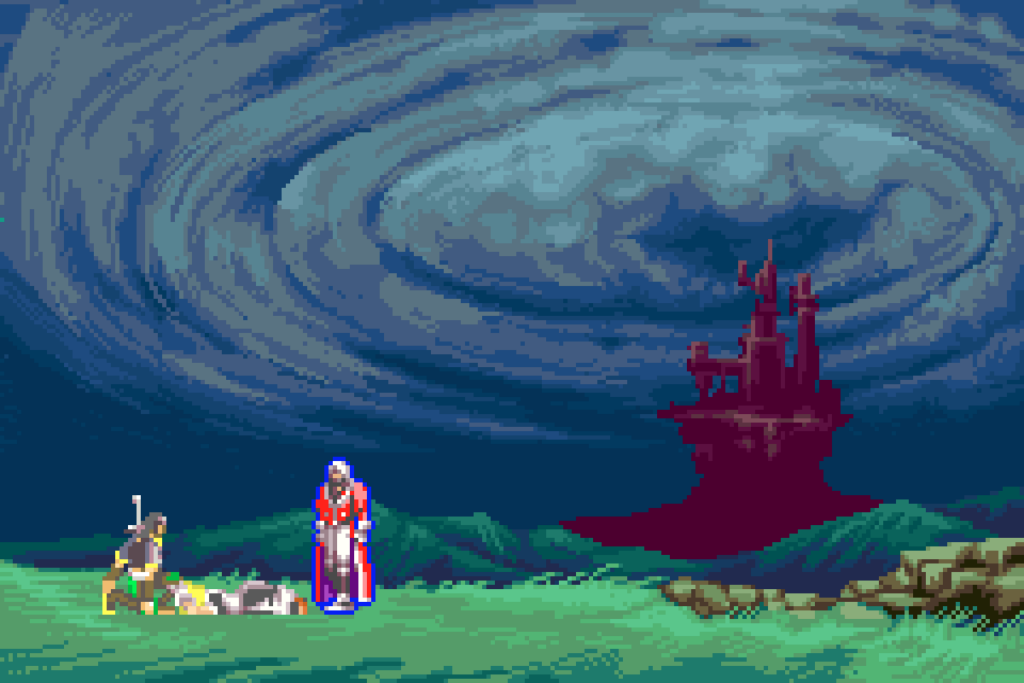

For what it’s worth, both castles nail their individual atmospheres. Castle A relies primarily on grounded architecture (albeit with plenty of abstracts) with an aesthetic that matches early to mid-game Castlevania stages. The color palette is obviously quite bright, but the general level layout and background details play up a sense of reality – which is important since Castle B is actually an apparition that exists on an astral plane. Aesthetically, Castle B strives for the visual chaos typically reserved only for the endgame. Save rooms are lifeless respites devoid of color, the sky outside runs blood red, and the architecture is in awful condition compared to Castle A. Torn curtains and decayed backgrounds help build Castle B as a harsh labyrinth lost to time & reality.

Exploration’s slow pace on account of jugging castles can make progress feel minuscule, but there’s almost always something to find if you backtrack to the wrong area early. HoD is loaded with secrets – not as robust as SotN, but admirable. Stat Potions are scattered between the two castles, there are a few optional bosses to fight, and it’s even possible to find some of Dracula’s lost body parts before the prompt to track them down. Harmony of Dissonance is actually fun to explore once everything pieces together and shortcuts stop being a luxury. The best part of the game is finally having free reign of Castle A + B as you comb through every nook and cranny to unlock the final boss.

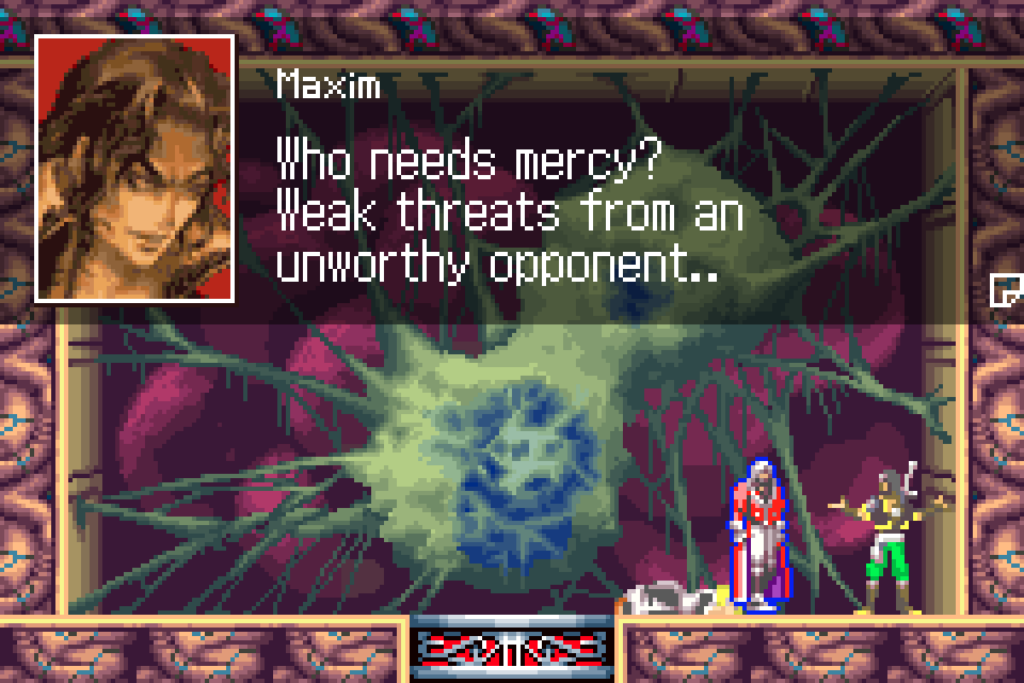

Backtracking is still a presence due to a few chokepoints, but it’s not as problematic as in the early game. The hunt for all six Dracula Parts adds focus to a directionless endgame and they’re genuinely well hidden, requiring better observational skills than the average Castlevania. The narrative allusion to Castlevania II: Simon’s Quest also helps add a greater sense of scope to the finale, Juste’s adventure mirroring his grandfather 50 years prior. Like Symphony of the Night and Circle of the Moon, Harmony opts for an intimate supporting cast around Juste. Maxim is the rival character ala Richter or Hugh, Lydie looks like Maria but is functionally Morris Baldwin, and Dracula takes a backseat until the final boss fight so a crony can serve as the main antagonist (in this case Death).

The story itself settles on being derivative for the sake of fan service, for the most part, resulting in a dry plot that’s carried by references to past games. Maxim is possessed by Dracula in the same way Richter was possessed by Shaft, also mirroring Hugh’s hostility towards Nathan in CotM through his warped relationship with Juste. Lydie’s arc mirrors Annette’s from Rondo of Blood to a T – both are damsels in distress who spend all game waiting for their respective Belmont to save them and can actually be neglected entirely. Harmony of Dissonance’s climax even apes Circle of the Moon: both games involve the main character interrupting an important ceremony tied to restoring Dracula’s full powers, ultimately fighting a warped version of the Dark Lord as the final boss. What differences there are in context mainly stem from Simon’s Quest and Symphony of the Night references.

Arguably worse than anything is how aimless the story feels. Castlevania games are ultimately about the gameplay, but Rondo of Blood, Symphony of the Night, and Circle of the Moon all put a fair bit of effort into their small bits of plot. Circle isn’t particularly compelling, but Rondo’s script is incredibly charming, and Symphony has all the qualities of a proper epic. Harmony of Dissonance is stitched together, its highs mainly reliant on nostalgia and lows pervasive. There’s no urgency to the plot, Death’s dynamic with Juste is laughably affable with none of the history the reaper shared with Alucard, and Maxim’s few cutscenes always leave something to be desired as far as story development goes. Really, the only particularly interesting thing about the story is the fact there are three multiple endings.

The normal ending is achieved by defeating the final boss in Castle A. Juste and Lydie make it out, but Maxim dies inside of the castle. The bad ending is attained by defeating the final boss in Castle B without wearing Juste & Maxim’s matching friendship bracelets. In this ending, Juste fails to save both Lydie and Maxim, ending the game on an incredibly bitter note where he’s forced to recognize his failure. The best ending can be seen by equipping Juste and Maxim’s bracelets before the final boss. Juste will be able to save both Maxim & Lydie, putting Dracula’s Castle behind them (and the fact Maxim kidnapped & bit his best friend’s girlfriend). None of the endings are particularly elegant, but they all bring Harmony to a notable conclusion in their own right. The normal ending is bittersweet, the bad ending embraces a dark outcome, and the best ending offers the game’s only real glimpse into Juste, Maxim, & Lydie’s relationship.

Harmony of Dissonance is at odds with itself. Trying to replicate Symphony of the Night was an ambitious goal that made HoD a much denser game than Circle of the Moon. Consequently, Harmony is also far more padded. Backtracking is a regular occurrence and it takes too long for exploration to find its rhythm. The fact there are two castles at play means navigational issues are just doubled down on. CotM was a brutally hard game that could barely be played on an original GBA, but it at least had a unique vision and is paced relatively well (albeit far from perfect). HoD, by comparison, is insultingly easy, painfully derivative, and at times even meandering. Juste’s controls are incredibly fluid, but they’re too refined for Castlevania’s combat loop. Magic just makes the game even simpler and most bosses are carried by presentation alone.

All this said, it’s surprisingly easy to turn the other cheek when it comes to Harmony’s dissonance. The story & castle are fragmented to a fault, but the gameplay never lets up and the pure directionless exploration is refreshing when approached with the right frame of mind. Juste may be too talented for his own good, but his fluid controls do keep combat mechanically engaging at all times (if a bit braindead in terms of actual enemy design). In spite of how derivative HoD may be in places, its atmosphere is completely unique and lends the game a strong artistic identity. Harmony of Dissonance fails to match Symphony of the Night in quality or carve a legacy of its own, but Juste’s time in Dracula’s Castle(s) rounds out into a respectable Castlevania sequel. Albeit one Igarashi should have tempered expectations for.

-

Features4 weeks ago

Features4 weeks agoGet Ready: A Top Isekai Anime from the 2020s Is Headed to Hulu!

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks agoSocial Gaming Venues and the Gamification of Leisure – A New Era of Play

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks agoSolo Leveling Snubbed?! You Won’t Believe Who Won First at the 2025 Crunchyroll Anime Awards!

-

Culture3 weeks ago

Culture3 weeks agoThe Global Language of Football: Building Community Beyond Borders

-

Technology4 weeks ago

Technology4 weeks agoIs Google Binning Its Google Play Games App?

-

Technology4 weeks ago

Technology4 weeks agoHow to Download Documents from Scribd

-

Guides4 weeks ago

Guides4 weeks agoBoosting and WoW Gold: Why Prestige and Efficiency Drive the Modern MMO Player

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks agoGamification and Productivity: What Games Can Teach SaaS Tools

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks agoFarewell to a Beloved 13-Year-Old Isekai Anime That Brought Us Endless Laughter

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoThis Upcoming Romance Anime Might Just Break the Internet; Trailer Just Dropped!

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks agoWait, What?! Tom & Jerry Just Turned Into an Anime and It’s Glorious!

-

Culture2 weeks ago

Culture2 weeks agoIs the Gaming Industry Killing Gaming Parties?