Features

Is Ico One of the Most Influential Games Ever?

20 Years Later: Ico

In 2001, the videogame landscape was different. The PS2 was king of the hill. PCs hadn’t yet become another kind of console. There was no Steam and no Good Old Games. Roger Ebert had yet to set the industry afire by dissing the medium. Videogames had been art for a long time – heck, the “is it even a videogame?” debate probably stretches back to 1983, to Jason Lanier’s Moondust – yet the idea hadn’t reached critical mass. Nowadays, of course, the debate’s more or less settled. We have the Computerspielemuseum in Berlin, the Smithsonian’s 2012 exhibition, and a growing academic literature (most of it from Scandinavia, for some reason). Even Ebert admitted defeat: “I was a fool for mentioning video games in the first place. I would never express an opinion on a movie I hadn’t seen.” But in 2001, this was all in the future.

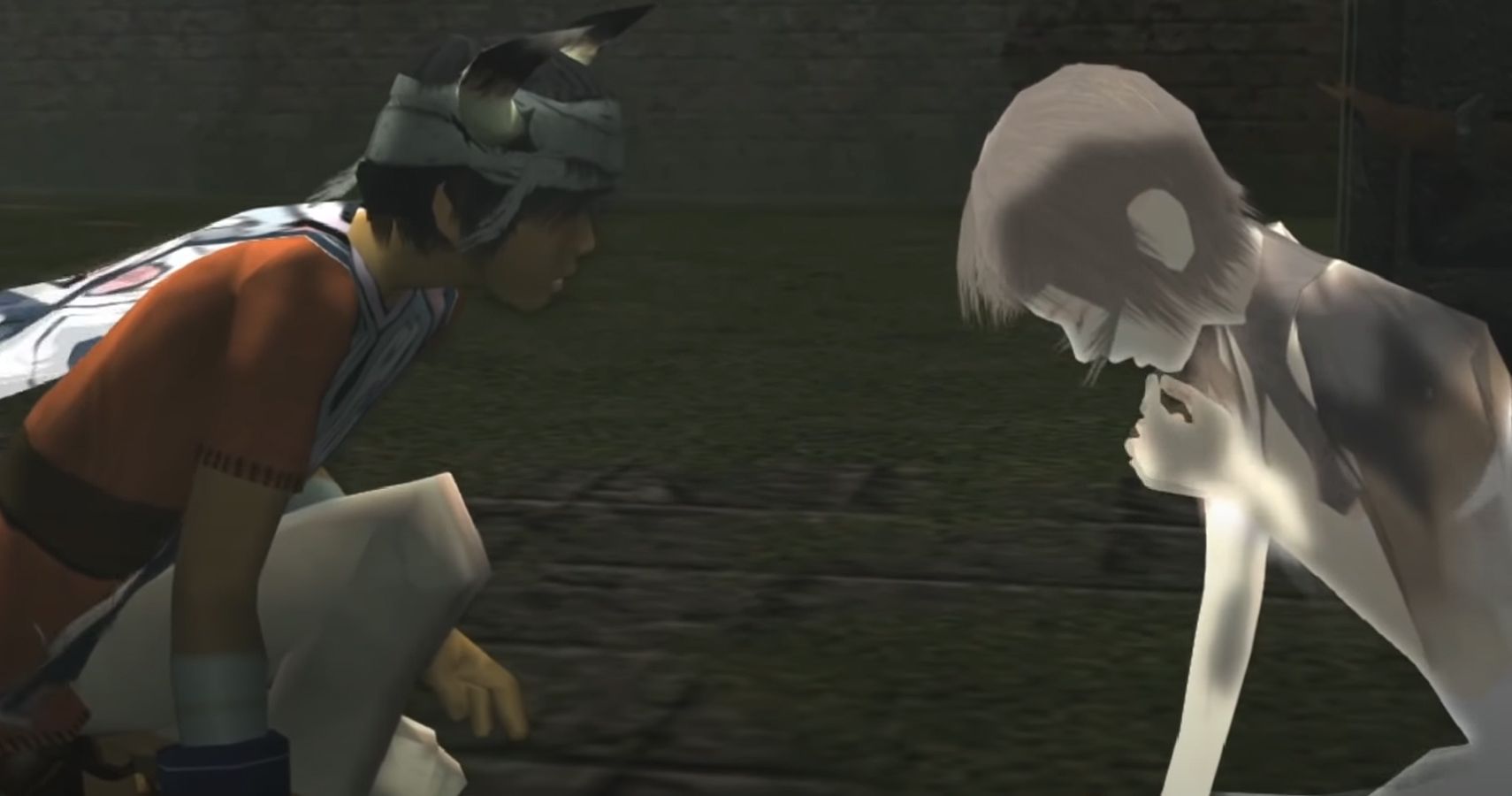

Then in September of that year, a little game came out called Ico, made for Sony’s landmark sophomore console by Fumito Ueda and his team. It was an odd title. You play a kid with horns who has no weapons or items save a sword or a stick. You’re trapped in a huge castle and must find a way out – though not alone. To unlock the magical gates standing in your way, you’ll need to bring along a mysterious girl who radiates white light and is excruciatingly passive. Though she claims to be running away from shadow monsters, she clearly wants to get caught. And when she’s not getting kidnapped, she can be found staring longingly at ladders or movable blocks. The mechanics behind her character haven’t aged well – either in terms of gameplay or in terms of sexual politics. It’s true the reason she’s so passive is not because she’s a woman but because she’s been kept in captivity all her life. The ending bears this out: after adventuring for several hours, she eventually learns to be, well, more proactive. Still, the game’s not exactly subverting traditional feminine roles (again, until the final moments, and then it’s too little too late).

Ico learned its lessons well. A cross between Zelda, Prince of Persia, and Myst, it reduces them to their essentials.

Thankfully, everything else about Ico continues to work its spell. Its graphics can still inspire awe: panoramic vistas of impossible Piranesi-like architecture, crumbling bridges over bottomless chasms, weathered ramparts and towers, gigantic gears and machines, idyllic gardens and temples with arcane technology… It’s all gorgeous (unless you don’t dig the limited color palette of greys and browns and faded greens, which I certainly do). The puzzles remain fun to think through. They might not overtax your brain, but they’ll keep you moving, swinging, and climbing, always transforming the castle, demolishing pillars and walls or repositioning platforms. You feel weak enough, as an under-equipped captive, to appreciate the story’s drama, but influential enough, as an interior decorator, to feel empowered.

Ico learned its lessons well. A cross between Zelda, Prince of Persia, and Myst, it reduces them to their essentials. No obscure head-scratchers, only spatial logic problems solved with switches and pulleys. No multiple dungeons and bosses and villages, only one complex environment and a single escape route. For seven or eight hours, players do the same thing: get used to their surroundings and access new areas, until no more is left unexplored. Narrative is hinted at. The few cinematics inspire more questions than answers. There are no side-quests or dialogue trees. Shadow monsters provide sporadic action, but it takes half a minute to dismiss them. Then it’s back to silence and emptiness, just you and your enigmatically passive companion.

Image: Sony

Ico was – and is today – brilliantly single-minded. To win is to learn the shape of the castle. A simple and simply powerful concept that, unsurprisingly, has influenced other masterpieces. According to Hidetaka Miyazaki, his Souls games basically exist thanks to Ico. And you can see the resemblance: the winding interconnected levels, the loneliness, the cryptic narrative, the medieval ambience, the unimaginable and unbuildable scale of the buildings – it’s all there. Souls, too, is single-minded. You’re in nowhere land swamped by reanimated skeletons and other unspeakable eldritch creatures and you must fight your way out – or in. That’s it. Focused, grueling, unforgettable.

Many more games have been lighted by Ico’s beacon. So many, in fact, that Wired even ran an article eloquently titled, “The Obscure Cult Game That’s Secretly Inspiring Everything,” which mentions Brothers: A Tale of Two Sons, Fez, Uncharted 3, and Rime. And we may imagine, too, that several recent games with vague yet crucial stories, mostly empty and beautiful locations, often mind-bending puzzles, and a definite stress on aesthetics and feelings, are all, in one way or another, whether consciously or not, Ico’s heirs: from Monument Valley to Kairo, Limbo, the Knytt games, Dear Esther, The Witness, Superbrothers, and Kentucky Route Zero (or, even moreso, Cardboard Computer’s earlier experimental doodle, Ruins).

Ico, of course, didn’t emerge from the ether. Myst, Zelda, and Piranesi are only some of its predecessors. There’s also the work of artist Giorgio de Chirico, whose sunbaked and unpeopled cityscapes are explicitly cited in the game’s cover art. And there’s Another World, with its classy, minimalist art style, from which Ueda derived his ethics of subtraction, of including only what’s necessary and leaving out the rest. But what Ico did – and what Shadow of the Colossus, Team Ico’s follow-up, later reinforced – was to announce that videogames were ready for their close-up. That they could make you care about other characters and build environments evocative of more than just eye-candy, of moods and ideas and states of mind. When Ebertgate exploded, it was Team Ico’s productions that were most frequently hailed as proof that videogames could be art. (Of course, being art, they’re always art, even when they suck – but that’s another article.) When the venerable critic recanted, or at least admitted that he shouldn’t have written what he did, his apologetic post was littered with conciliatory screencaptures of Shadow of the Colossus.

Art doesn’t exist in isolation; it needs an audience. Ico didn’t find its public when it came out because such a public didn’t exist – so Ico helped create it. As writer Chris Kohler observes, in his aforementioned Wired article, “when a player today looks at a game with a stark visual style and a minimalist approach to gameplay mechanics, they no longer struggle to understand what sort of game it is. ‘Oh,’ they just think, ‘so it’s like Ico.’” It was not the first to do anything. It was, rather, a unique creative direction that shaped the conversation to come and is still a recognizable model for video game art.

-

Features4 weeks ago

Features4 weeks agoGet Ready: A Top Isekai Anime from the 2020s Is Headed to Hulu!

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks agoSocial Gaming Venues and the Gamification of Leisure – A New Era of Play

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks agoSolo Leveling Snubbed?! You Won’t Believe Who Won First at the 2025 Crunchyroll Anime Awards!

-

Culture3 weeks ago

Culture3 weeks agoThe Global Language of Football: Building Community Beyond Borders

-

Technology4 weeks ago

Technology4 weeks agoIs Google Binning Its Google Play Games App?

-

Technology4 weeks ago

Technology4 weeks agoHow to Download Documents from Scribd

-

Guides4 weeks ago

Guides4 weeks agoBoosting and WoW Gold: Why Prestige and Efficiency Drive the Modern MMO Player

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks agoGamification and Productivity: What Games Can Teach SaaS Tools

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks agoFarewell to a Beloved 13-Year-Old Isekai Anime That Brought Us Endless Laughter

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoThis Upcoming Romance Anime Might Just Break the Internet; Trailer Just Dropped!

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks agoWait, What?! Tom & Jerry Just Turned Into an Anime and It’s Glorious!

-

Culture2 weeks ago

Culture2 weeks agoIs the Gaming Industry Killing Gaming Parties?

Gene

September 25, 2016 at 12:36 pm

What an awesome article 🙂

Note5

September 25, 2016 at 3:11 pm

Enlightening article. Bravo!

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uVihDspGt6k