Features

The Legend of Getting Lost: Exploration in Old-School Zelda to Breath of the Wild

Exploration carries less weight when you can’t get lost.

The oldest Zelda games throw you into a world, tell you to explore, and don’t necessarily care if you get lost. Not knowing where to go or what to do next is commonplace. The Legend of Zelda and The Adventure of Link are games you almost need to play with guides if you want to complete them in a reasonable time frame, let alone do and see everything. At the same time, it’s deeply rewarding if you can beat the games by “the rules,” a sentiment that mainly applies to the series’ earliest titles. Old-school Zelda reflects a design philosophy the medium has moved further away from with each generation. It’s “disrespectful” towards a player’s time to let them get lost, and “unfair” not to highlight where to go or what to do next. Offering context is important, but modern games pad themselves with guidance at the detriment of the adventure. Exploration carries less weight if a game won’t let you get lost.

Getting lost in a video game is more than no longer recognizing the space you’re in or not knowing what to do next. It’s a feeling tied to progression, which in turn makes it more rewarding to find your way. A good adventure should demand your attention and focus at all times. Exploration should be relaxing to an extent, but you shouldn’t be able to coast from set piece to set piece. If done well, it’s simply more fun to let a player get lost rather than guide them every step of the way. Being lost doesn’t mean being bored so long as everything is built on good game design. It encourages you to engage with the world in a way you normally wouldn’t, organically discover new things, and naturally immerse yourself in the game.

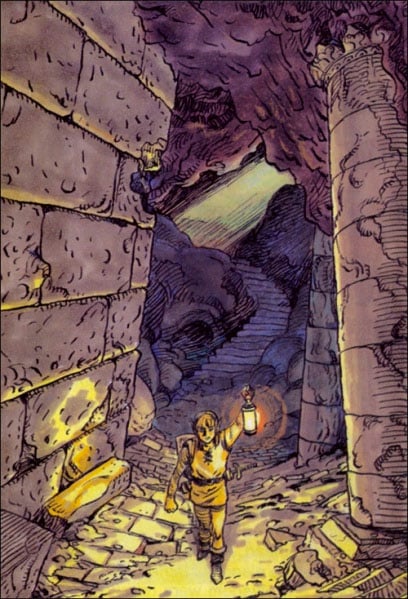

Using the NES Zelda games as examples, gameplay doesn’t grind to a halt when you get “lost,” and you more than likely will on a fresh playthrough. There may be guidance along the way, but little enough where each game is comfortable leaving you to your own devices for the most part. The onus is placed primarily on you to complete your adventure. The Legend of Zelda wants you to see yourself as Link — as a tried & true adventurer. Letting you get lost is just another way of blurring that line between avatar and audience. It’s a dose of reality great adventures need to stand out.

In the liner notes for “The Legend of Zelda: Sound & Drama”, series creator Shigeru Miyamoto explains what he wants players to get out of Zelda,

“I wanted to create a game where the player could experience the feeling of exploration as he travels about the world, becoming familiar with the history of the land and the natural world he inhabits . . . Adventure games and RPGs are games where you advance the story through dialogue alone, but we wanted players to actually experience the physical sensation of using a controller and moving the character through the world.”

Zelda is a franchise founded on capturing the spirit of adventure. You learn how to navigate a world all on your own, and take in & immerse yourself in new spaces. You get lost, but you gain time to get better at the game, track down secrets, and maybe even find new items to help you access new areas. The series’ earliest entries are designed around the simple pleasure of coming to your own conclusions: of discovery. Navigation in an adventure game should be more than just moving from point A to point B — it should require effort and almost be a puzzle in & of itself. You’re bound to get lost, but the payoff is worth it and rooted in your own accomplishments.

The risk of getting lost makes the gameplay loop more engaging since you need to invest mental effort to proceed. You have to pay attention, go out of your way to track down clues, and develop an intuition for spotting secrets. You can argue that this is an “artificial” way of extending game length, but an adventure needs to have room for getting lost to carry the right impact. A Link to the Past can be completed in 5 hours if you know what you’re doing, but it’s a game Nintendo envisioned taking 40 hours to finish on a fresh playthrough. Those extra 35 hours aren’t padding or filler — they’re the story of your playthrough. If the gameplay loop is good enough and a world engaging enough, getting “lost” is nothing but a good thing. In fact, this was a key element Miyamoto wanted to invoke from the very beginning,

“I wanted to create a game world that conveyed the same feeling you get when you are exploring a new city for the first time. How fun would it be, I thought, if I could make the player identify with the main character in the game and get completely lost and immersed in that world?”

Miyamoto likens fun in Zelda directly to losing yourself, both in the sense of being navigationally lost and through pure immersion. In practice, it is fun to get and be lost in Zelda. Getting lost in the original Legend of Zelda gives you a chance to do things out of order. If you can’t find the first dungeon, you might stumble upon the second instead. You can find enough Heart Containers to unlock a new sword before you ever step foot in a dungeon if you explore thoroughly enough. You can grind Rupees to buy new equipment. No matter what you do, you’re exploring the world and developing a better understanding of it, which will help you navigate later. You just need to play the game and figure it out yourself. That’s compelling in its own right.

The Adventure of Link trades the first game’s immediately open world for segmented level design that naturally directs you around Hyrule. Getting lost is less a matter of where to go and more so what to do. Navigating aimlessly won’t get you anywhere. Instead, you have to pay attention to NPC dialogue and your surroundings. Towns have a respectable hustle & bustle for 8-bit, capturing that city-like feeling Miyamoto was going for. You can even ask others for directions. Taking the game’s sheer difficulty into account, being lost also gives you valuable time to not only grind experience to raise your stats, but actually master the core combat. A totally straightforward Zelda II would give you no time to develop your skills before the challenge spikes or require you to figure out each town’s quest on your own. The more time you spend in a game’s world, the deeper a connection you can form with it.

Neither game handles exploration in the exact same way, but they share important design fundamentals that may result in players getting lost. There’s an inherent trust that the player doesn’t need (or want) overt guidance; an expectation that players have enough agency to gather context on their own; and an understanding that getting lost is an intrinsic part of the fun. You just can’t get lost in later Zelda games, not truly and not in the same sense. Exploration stops being about discovering the world around you in favor of discovering solutions to linear progression puzzles. This approach has its own design merits, of course, but it’s at the expense of an adventure’s more naturalistic qualities.

A Link to the Past marks a notable turning point in how Zelda approaches the concept of “getting lost.” Between 1991 and 2013, the series progressively became less comfortable with the idea of letting the player get and be lost. This is a gradual change, however, and ALttP settles on a healthy compromise between guided direction and open-ended exploration later entries lack. Three games in, Nintendo still wanted players to get lost — so much so that Miyamoto envisioned a puzzle that would take a year to complete, “I wanted something that players could get so lost in, it would take them a whole year to finish” — albeit in a more structured capacity.

The first quarter of A Link to the Past tutorializes exploration. You’re introduced to the first of two overworlds, then guided from dungeon to dungeon in a fixed order (Eastern Palace, Desert Palace, Tower of Hera, Hyrule Castle, and the Dark Palace) before things open up. It’s only after beating the Dark Palace where you’re given free rein to explore the Light and Dark Worlds in tandem, with the game leaving you to your devices all the way to the end. This doesn’t mean you’re directionless, though. A Link to the Past introduces quality of life features to make exploration “smoother.” Your map marks where each dungeon is located, even outlining which order to tackle the Dark World in from 1 – 8. While useful, this makes it feel more like a map to a theme park than a map for an adventure.

Fortunately, the Dark World features progression checks to make sure players who just follow the map will eventually get lost or stuck. You can’t beat the game without the Flippers or Ice Rod — two items you can track down before ever entering the Dark World — but you won’t find them if you only follow the “intended” sequence. The game does a lot to keep you from getting lost, but you cannot progress unless you intentionally lose yourself in the world. ALTTP’s design conventions reward player-driven exploration, while directing you towards the “main event.” You have The Legend of Zelda’s open-ended approach mixed with The Adventure of Link’s structure. It’s a best-of-both-worlds scenario that makes A Link to the Past friendlier than the NES titles while still remaining philosophically recognizable.

As the main codifier for later Legend of Zelda games, Link’s Awakening is when clear structure starts taking priority over freeform exploration. LA is the first Zelda where the story guides you between dungeons in a set order. The overworld has a Metroidvania-esque quality that keeps you out of key areas until it’s the designated time to visit them. An owl tells you what to do and nudges you in the right direction through mandatory cutscenes. So long as you make an effort to speak with NPCs and pay attention to dialogue, you will always know where to go and what to do next. Link’s Awakening’s world is immersive enough where you can still lose yourself in it, but you’ll rarely lose your sense of direction.

By Ocarina of Time, you can’t get lost so much as you can get stuck. The map shows you which region you should visit next. Navi reminds you exactly what to do every time you boot up the game or idle for too long. NPCs guide you in the right direction and regularly offer solutions or hints, even for puzzles audiences assume go untelegraphed. Feeding a fish to enter Jabu-Jabu is widely regarded as one of the most obtuse sequences in Ocarina of Time, but a Zora in Zora’s Domain spells out what to do if you talk to them. These changes are rooted in concerns Miyamoto has always had regarding Zelda, only amplifying with each sequel,

“Zelda was a game where we were very concerned whether players would understand what they were supposed to do.”

For Nintendo, making sure the player understood what they were supposed to do eventually became too important to ignore. The Legend of Zelda’s ever-changing relationship with exploration can be summed up with a single quote from series producer Eiji Aonuma, “I thought that making the user get lost was a sin.” Zelda games released after Ocarina of Time and before A Link Between Worlds do not want you to get lost or feel stuck. Exploration is more about puzzle solving, combat challenges, and finding the occasional secret than natural discovery. With exceptions, you tackle one major area at a time with a clear understanding of what needs to be done. You’re discouraged from getting “distracted.” This is barely noticeable in Ocarina of Time’s immediate sequels, but becomes a bigger issue the deeper into the franchise you get.

In Majora’s Mask, you always know exactly where to go, what to do, and in what order by following a fixed sequence of events in-game. The critical path is very easy to follow, but the bulk of gameplay is at least made up of side content, which is easy to lose your sense of direction with. Like Link’s Awakening, the stories in Oracle of Ages & Seasons direct you where to go and the overworld is gated into chunks ala a Metroidvania. Seasons lets you do two dungeons out of order and Ages has harder puzzle design that can trip players up, but you otherwise won’t get lost so long as you pay attention.

The Wind Waker’s critical path is still linear and story-focused, but the last act opens with an entirely exploration-driven quest to kick off the finale with. The Triforce Hunt feels like the last time a Zelda game actually felt comfortable letting the audience get lost. You’re thrown into a world, told to explore, and left to your own devices until you fully assemble the Triforce. It’s a beat directly modeled after the original Zelda’s gameplay loop. The key difference between the first Zelda and The Wind Waker is a matter of when their worlds open up: the beginning versus the end. Even then, the international release added a chart that removes all of the quest’s actual exploration.

The original Japanese release forces you to explore the Great Sea and reference your Sea Chart and Treasure Maps to find each Triforce piece. You have to act like a real adventurer, pour over your notes, and figure out where to go next. If you don’t, you will get lost. The IN-credible Chart added into the international release simply shows you where on your Sea Chart each Triforce is hidden. You can ignore the chart if you’d like, but most players will immediately open it and deprive themselves of natural discovery. Considering how disliked The Wind Waker’s Triforce Hunt is, maybe Nintendo was right to add the IN-credible Chart, but it only reflects a shift in priorities where the series no longer felt comfortable letting players get lost.

The Wind Waker’s immediate sequels (The Minish Cap, Twilight Princess, Phantom Hourglass, Spirit Tracks, and Skyward Sword) are even more restrictive. It’s hard to get lost or stuck since gameplay works around the story’s pace and always contextualizes what you need to do, where you need to go, and often how. With Phantom Hourglass as the sole exception, you can’t even do dungeons out of order. Progression is framed more like a theme park tour than a full-blown adventure. Time spent organically exploring is often replaced with grandiose set pieces. By Skyward Sword, the open-ended exploration and risk of getting lost that defined early Zelda was all but gone.

A Link Between Worlds was the series’ first attempt at recapturing classic Zelda’s design philosophies, setting an important (albeit comparatively restricted) precedent for Breath of the Wild — do whatever you want, whenever you want. It’s a step closer to The Legend of Zelda’s roots, but still not quite on the same level. While you can play through most of the game in any order, that also means you’re not going to get lost. You can’t, because there’s no “wrong” way to turn. It’s as much a step forward, as it is a step sideways. A Link Between Worlds’ connection to classic Zelda mainly comes from the game leaving you to your own devices, not in a capacity to let you get lost or its own sense of discovery.

Breath of the Wild’s exploration is more in-line with old-school Zelda in that you’re free to explore at your leisure, but the nature of Hyrule’s open world means you won’t get lost in the traditional sense either. Breath of the Wild is the closest a Zelda game has ever come to matching the series’ original spirit of adventure, but there’s one glaring disconnect. You never have to actually think about where to go or what to do next because you never need to do anything or go anywhere in particular. Philosophically, Breath of the Wild is a very different game than the original Zelda, A Link to the Past, or Ocarina of Time. Being “lost” means something totally different here. It has more to do with entering and exploring a new area rather than not knowing your next course of action. This results in the opposite problem titles like Twilight Princess and Skyward Sword have.

Where those games always make it obvious where you need to go or what to do, Breath of the Wild never needs to tell you where to go or what to do because it genuinely does not matter. The game is entirely player-driven beyond the tutorial, to the point where you can go defeat Ganon and roll credits as soon as you want if you’re skilled enough. It’s a different approach to game design altogether, rather than a remedy for the series’ railroaded exploration. You discover the world around you rather than solutions to puzzles or new items and hints to make progress. Payoff is replaced with pure wonder. This can be seen in how BotW inadvertently abandons several of the series’ staple features, like proper dungeons, equipment checks, and progression puzzles. Breath of the Wild also does a disservice to its exploration through its quality of life features. An incredibly detailed mini-map and custom waypoints offer more direction than any Zelda before it.

People are quick to hail Breath of the Wild as the second-coming of old-school Zelda, and while it’s not hard to see where they’re coming from, we’re not quite there yet. Breath of the Wild is just a middle ground between early Zelda’s free-form overworlds and later Zelda’s theme park-based design conventions. A step in the right direction for exploration’s sake, but still not the ideal given what was compromised. Navigation is less of a puzzle and more a simple state of being. Immersing and losing yourself in the world is arguably the easiest it’s been, but the tension of being lost — that satisfaction of payoff and finding the right solution — has no real place in a game like Breath of the Wild.

Being lost can be frustrating, but it’s that frustration that makes it so much more rewarding to figure out where to go or what to do next. Modern gaming conventions inch closer towards instant gratification above all else with each passing generation. The audience doesn’t need to be actively entertained every second of the game. It’s okay to let players get stumped or hit a wall. You don’t always need to know where to go, or even why. Sometimes all an adventure needs is a cave, a crossroad, and an adventurer willing to explore. So what if you get lost? At least you’re getting lost on your own terms.

Losing yourself and making an adventure your own is ultimately the appeal when it comes to the original Legend of Zelda. If the adventure is fun, it shouldn’t matter if you get lost. Later Zelda games aren’t bad for not letting the audience get lost, but they’re missing a key element that gives exploration another layer of weight. Quality of life fixtures are deemed necessary for modern audiences, but they’re a double-edged sword that teach bad gameplay practices when overused. You stop paying attention to all your surroundings and only start focusing on the “key information.” Mini-maps steal focus away from the level design, waypoints defeat the purpose of exploration, and a world with no progression checks sticks out just as much as too much guidance.

Letting players get lost is not a sin, it’s a sign that a game wants more out of you and an opportunity to mentally engage yourself on a deeper level. If you just play games to beat them, watch the credits roll, and move on to the next, then getting lost is no fun. But if you meet an old-school Zelda on its level and just play, the fact you can get lost at all is half the reason they hold up as well as they do. It’s not a flaw, it’s a feature.

Yet it makes perfect sense why Nintendo would want to keep players on track: a lost player is someone who potentially drops the game altogether because they stop having fun. Zelda is also a dynamic enough series where a lack of freeform exploration is offset in different ways. Later game’s worlds don’t stop being fun or immersive just because you can’t get lost anymore. Phantom Hourglass and Spirit Tracks are defined by the Nintendo DS’ unique capabilities; Twilight Princess and Skyward Sword make up for their railroaded adventures with excellent dungeon design and memorable set pieces; A Link Between Worlds and Breath of the Wild want you to play at your own pace and on your own terms in settings where there are multiple correct answers. There’s value in all these gameplay styles, but they’re not inherently incompatible with what came before.

Nothing else quite shares the sense of discovery and adventure found in the original Zelda, The Adventure of Link, and A Link to the Past. These games may not respect your “time,” but they respect your intelligence and willingness to rise up to the challenge. There’s value in reclaiming that. A Link Between Worlds & Breath of the Wild at least demonstrates Nintendo is willing to reflect on the series’ past to push it forward. Now it’s just a matter of fully committing. Zelda’s sin was never letting players get lost, it was losing touch with its adventurer’s spirit.

-

Culture4 weeks ago

Culture4 weeks agoMultiplayer Online Gaming Communities Connect Players Across International Borders

-

Features4 weeks ago

Features4 weeks ago“Even if it’s used a little, it’s fine”: Demon Slayer Star Shrugs Off AI Threat

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks agoBest Cross-Platform Games for PC, PS5, Xbox, and Switch

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks agoThe End Is Near! Demon Slayer’s Final Arc Trailer Hints at a Battle of Legends

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoPopular Webtoon Wind Breaker Accused of Plagiarism, Fans Can’t Believe It!

-

Features4 weeks ago

Features4 weeks ago8 Video Games That Gradually Get Harder

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks agoDon’t Miss This: Tokyo Revengers’ ‘Three Titans’ Arc Is What Fans Have Waited For!

-

Game Reviews2 weeks ago

Game Reviews2 weeks agoFinal Fantasy VII Rebirth Review: A Worthy Successor?

-

Guides3 weeks ago

Guides3 weeks agoHow to buy games on Steam without a credit card

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoSleep Meditation Music: The Key to Unwinding

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoThe 9 easiest games of all time

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks ago2025’s Best Gaming Laptops Under $1000 for Smooth Gameplay

Constantine

November 11, 2022 at 2:35 pm

Dude do you know ducking dark souls talking about getting lost ,zelda is a baby games compared to that , dark souls fucking throws you with a broken sword and no place to go to find your self dead in five minutes