Features

The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess: A Nintendo GameCube Swan Song

“The whole world is expecting the greatest Zelda game ever, isn’t it?”

– Satoru Iwata on The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess

Legend tells that the swan sings a beautiful song right before its death, ending a life of silence on a powerful note. While there’s no actual truth in the legend (and has been disputed as early as AD 77,) “swan song” has become a catch-all term to signify one last great work of art. The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess is best known as a Nintendo Wii launch title, but director Eiji Aonuma intended for the game to help “the GameCube go out in style.” In retrospect, thinking of Twilight Princess as a Wii game doesn’t exactly do it many favors – especially when Skyward Sword outdoes its motion controls on every meaningful level. The Wii port isn’t reflective of TP in earnest. Twilight Princess is a swan song by definition and it’s best to see Nintendo’s 13th mainline Zelda for what it really is: the very last GameCube game.

Despite a legacy intimately tied to the Wii, Twilight Princess was always a better experience on the GameCube. The Wii offers crisper resolution and a wider field of view, but at the expense of mirroring the entire game (hurting the cinematography as a result) and replacing swordplay’s most sophisticated control scheme yet with relatively surface level motion controls. Simply flipping gameplay so Link is right-handed and east becomes west reshapes Hyrule in a disconnected manner, both from Zelda’s geography and reality. The Wii’s world looks and feels off because it is off. Mirroring the perspective a game was designed in makes for a good challenge ala Master Quest, but it’s at the expense of deliberate overworld and cinematic details.

A common criticism lobbed at Twilight Princess’ graphics is that it’s too realistic, Nintendo seemingly unlearning the lesson The Wind Waker taught them – realism isn’t always realistic. Considering the game sold nearly five times as much on the Wii than the GameCube, most audiences did play a version of Twilight Princess that wasn’t grounded in actual realism. It’s not hard to adjust to the mirrored gameplay and cinematics, but nothing looks as natural as it should. Accessories on clothing are out of place, the camera’s focus isn’t always where it needs to be during cutscenes, and Hyrule’s geographical flip distracts from cohesive worldbuilding.

The Wii port also features a semi-fixed camera on account of the Wiimote lacking a second analog stick. This might seem like a nitpick at its core (and it is,) but preventing players from rotating the camera also prevents them from seeing the full benefit of Twilight Princess’ art direction. The game isn’t realistic at the expense of realism, but a natural evolution of the aesthetic seen in Ocarina of Time & Majora’s Mask. The development team originally even intended to stick with The Wind Waker’s cel shading, only relenting because Toon Link’s now more adult-like proportions were lending themselves poorly to horseback gameplay. Most importantly, there was still a conscious artistic understanding to avoid photo realism.

“Well, among the artists it was clear from the start that we would not pursue photorealism in this game. We didn’t see any reason to engage the competition in a struggle over who could make the most photo-realistic game or any significance in attempting to recreate the real world for that matter. Rather, we felt that it would be more meaningful to create something we wanted to make, and then show the world what kind of game can be made when you have that kind of passion.”

– Satoru Takizawa, Art Director

It’s worth keeping in mind how played out the Toon Link aesthetic was at this point. The Wind Waker’s toon shading had become The Legend of Zelda’s de-facto art style for four games straight (The Wind Waker, Four Swords, Four Swords Adventures, and The Minish Cap) with little visual evolution from 2002 to 2004. Zelda was in need of a change and Twilight Princess’ blend of realism & fantasy was the clear answer. The Legend of Zelda has always had a darker toner lurking in the background. Majora’s Mask was the first game to truly embrace how morbid the franchise could get, but it did so in an intentionally detached manner. Twilight Princess fashions itself as a traditional Zelda, albeit more mature in tone and scope.

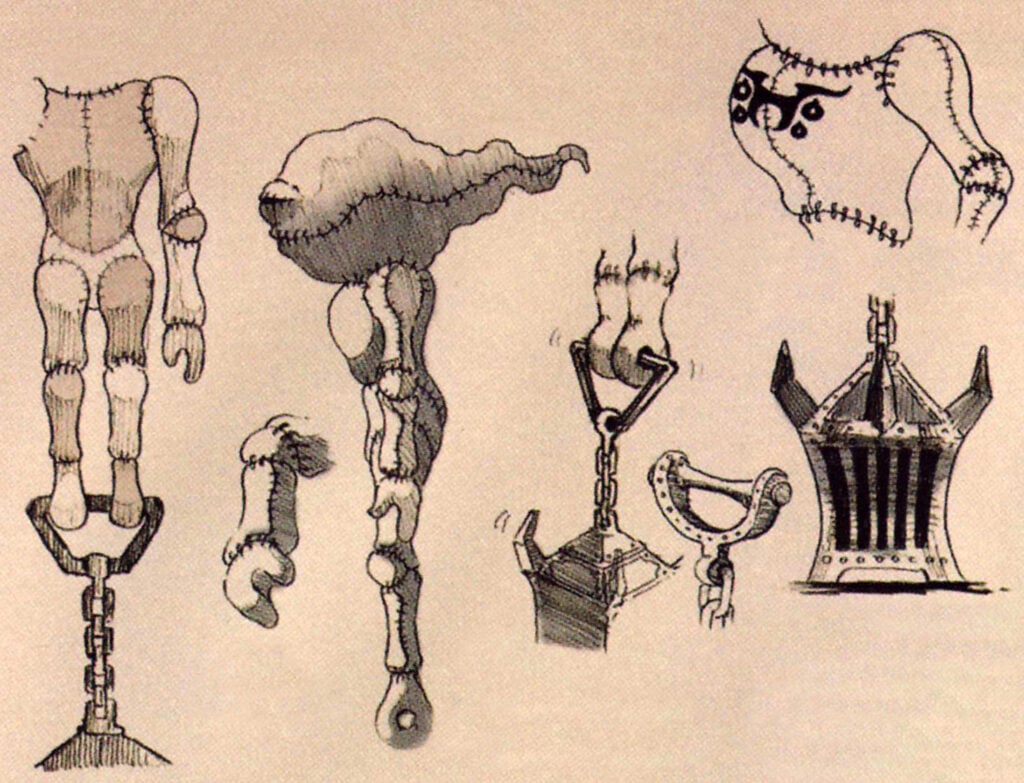

Artistically, this means utilizing a darker color scheme; designing characters with more defined & discernibly “realistic” features; and framing the series’ classically epic storytelling around body horror, the violence of war, & outright political drama. It’s easy to dismiss Twilight Princess’ maturity as a superficial attempt at being dark, but that’s doing the game a disservice. The Legend of Zelda’s trademark funkiness is still very present. Goron nipples are literally rock hard, Zora soldiers wear goofy fish helmets, and the average Hylian is hyper-stylized to the moon & back. The sign of good character design is the ability to recognize someone by their silhouette, and Twilight Princess has an incredibly well-designed cast – with Link as the clear standout.

“The new Link is wonderful, isn’t he? It won’t be easy to make something as good as this again. Even by Nintendo standards, this is first-rate.”

– Shigeru Miyamoto, Producer

A darker Zelda naturally needs a darker Link. Longtime series illustrator Yusuke Nakano was brought on to redesign Link after Yoshiki Haruhana fulfilled the role in The Wind Waker, envisioning the hero somewhere between 25 and 30. This older hero was quickly vetoed, however, with Nakano being given explicit direction to make Link closer to how he looked in Ocarina of Time. Even still, there are clear differences between the Hero of Time and the new Link. Concept art notes in Arts & Artifacts also label Link’s redesign as “cowboy,” playing up his backstory as a farmhand. In contrast to Ocarina of Time, the Hero of Twilight has defined muscles, a sterner face, and chainmail under his tunic to serve as armor.

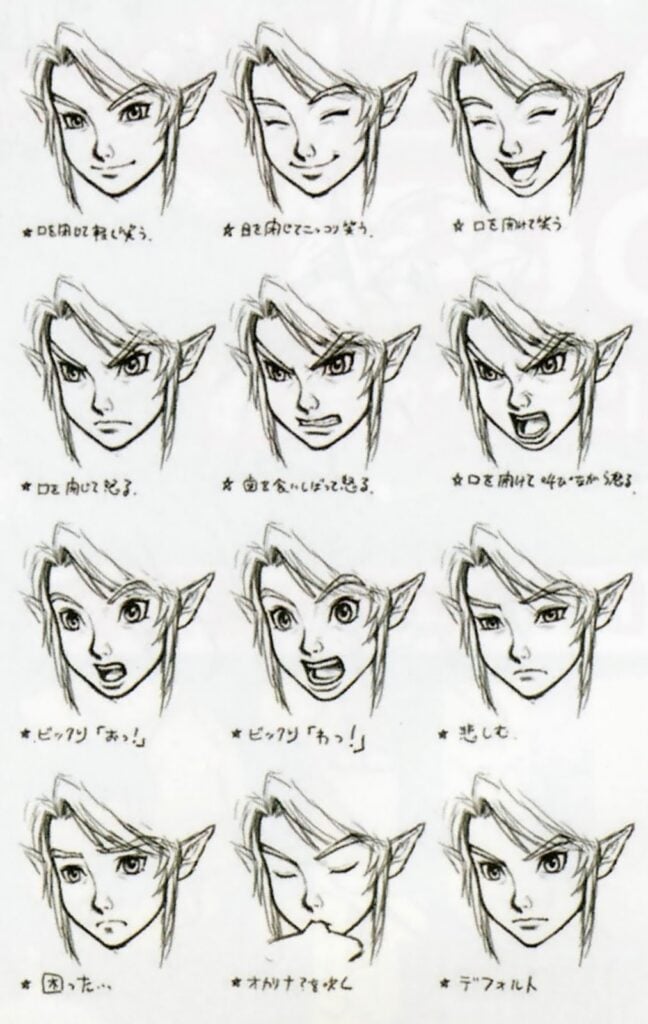

One of the largest benefits from cel shading was the range of emotion it offered Link in The Wind Waker. There’s no denying that Toon Link is still the most expressive interpretation of the character yet, but Twilight Princess is full of facial expressions for Link. The art direction naturally doesn’t allow Link’s emotions to telegraph as clearly, but he’ll react like a human during cutscenes – smiling and frowning when appropriate. Link scowls & furrows his brow when locked onto targets (though it’s hard to see without manually moving the character.) Link also has an entire sheet of concept art that’s just expressions, as if to prove the art of Twilight Princess could retain The Wind Waker’s emotional range.

Shigeru Miyamoto once defended The Wind Waker art style by warning against the side effects of realism in gaming; “The problem is that the more realistic a game gets, the more jarring it is when something unrealistic happens.” Twilight Princess isn’t as stylized as The Wind Waker, but its art direction avoids the pitfalls of photorealism and abides by Miyamoto’s philosophies. Link’s actions, reactions, and movements in-game are the most natural they’ve been. There’s no stiffness to how Link moves and it’s all inferred by good character design.

Just as much care was put into Link’s controls, resulting in incredibly tight gameplay. Swordplay has been reworked so Link can slash while walking along with allowing players to simply unsheathe their blade without attacking. Link’s movements are fluid – perfect for the more involved combat – and L-Targeting has been tweaked so Link automatically raises his shield while smoothly locking onto enemies. The only real problem with Link’s controls is that he slows down considerably when climbing vines or swimming, but this at least adds to the realism on display.

Any game releasing at the end of a console’s life cycle can benefit from pushing its hardware to the limits. It’s easy to take for granted just how well Twilight Princess runs on the GameCube. Gameplay runs at a stable 30 frames per second with rare dips, performing better than the HD remake on the Wii U. There are next to no discernible load times, with quick fadeouts carrying the heavy lifting. All of Hyrule Field is available as one giant area and dungeons never feature load screens in a generation where loading had become an accepted norm.

There’s also an impressive commitment to little details that are easy to overlook. Liquid inside of bottles actually move realistically when Link tilts them to drink, leaving residue on the glass. Planks and pieces of wood float in water – a detail Shigeru Miyamoto in particular was proud of. Children duck out of the way when you swing your sword at them; Link’s clothes darken when he’s in water & stay that way until he dries; mirrors are actually reflective & follow your movements realistically; and wind tunnels will actually drown out the music in some cases as if Link’s own ears are clogged.

The smartest way Twilight Princess pushes the GameCube is through lighting. Lighting is how Twilight Princess ultimately makes itself stand out artistically. Bloom was fairly commonplace in 2006, but the graphical glow that coats the game’s visuals is a beast in and of itself. Twilight Princess’ approach to bloom is very deliberate, highlighting characters & structures only as a means of establishing atmosphere. Lighting also shifts gradually as time passes, with the sky going through an assortment of colors that rain down on Hyrule. It’s not unusual to see mountains dyed pink as the sun sets, and the night sky shines brilliantly with flickering stars. Bloom is applied intelligently and nothing glows out of place, everything rendered naturally in the light around them.

When it comes down to it, it’s twilight that best defines Twilight Princess. The Twilight Realm is bathed in a serene twilight, as unsettling as it is tranquil – a land lost to perpetual dusk. Everything in the Twilight Realm is cast in an aggressive glow, distorting Hyrule’s visuals to the point of feeling uncomfortable. The denizens of the Twilight Realm are eldritch in appearance and the music is intentionally unpleasant, turning Hyrule into an oppressive & visually hostile kingdom. But there’s beauty in the twilight. “While care was given to make the encroaching Twilight Realm feel uncomfortable to motivate players, developers made sure not to make it so unpleasant that players would stop playing.” (Hyrule Encyclopedia 279) Hyrule lit by dusk is atmospheric – the kingdom torn apart by flickers of black and shades of dull gold in itself a moody sight.

Hand in hand with the Twilight Realm is Twilight Princess’ main gimmick: Wolf Link. While most humans become spirits in the Twilight Realm, the Triforce of Courage protects Link and turns him into a wolf when the province near his home village is overrun. Crucially, Wolf Link was suggested by Aonuma as a response to the team developing a game in the spirit of Ocarina.

“The initial theme I had in mind was naturally to make the first realistic Zelda since Ocarina of Time. But I didn’t dive in with only that aim in mind. I wanted to shake up the Zelda concept a little. That’s why early on, I brought up the suggestion that this time Link should transform into a wolf. I really felt that we needed a new twist of some sort.”

– Eiji Aonuma

Further defying this realism was the fact Link’s “wolf form was designed using cartoon techniques to impart a fairy tale quality not seen in his human form.” (Hyrule Historia 171) Wolf Link isn’t as fleshed out a gimmick as Ocarina of Time’s traveling or The Wind Waker’s sailing, but it’s appropriately Zelda. Turning Link into a wolf also introduces players to the Twilight Realm in a morbid fashion. Link is transformed against his will, imprisoned in Hyrule Castle, and forced to break out of a spirit infested dungeon. Princess Zelda is a prisoner in her own home and Link’s freedom is only met with another dive into the Twilight.

Wolf Link is Twilight Princess’ way of asserting its own identity independent of Ocarina of Time. Link was supposed to originally begin the game in his transformed state (Hyrule Encyclopedia 279.) This introduction would be in keeping with Aonuma’s direction on Majora’s Mask, which opens with Link being transformed into a Deku against his will. Twilight Princess’ final prologue eases audiences in, but starting as Wolf Link would have been a much bolder introduction while speaking to TP’s values as a game.

Introducing Wolf Link as early as possible could have also helped better frame the Tears of Light set-pieces littered throughout the first half of the game. Hyrule has already been overcome by Twilight by the time Link’s adventure begins proper, requiring him to repeatedly enter infested areas and become a wolf all over again. Upon entering an area for the first time, Link will need to collect all the Tears of Light in a region in order to dispel the Twilight. In practice, these ended up some of the most criticized sections in the game by slowing down the pace and withholding exploration until Twilight is cleared.

The Tears of Light manifested from a desire to bridge the gap between overworld and dungeon design. “Every Zelda game up to this point was clearly divided between an overworld and dungeons. Developers wondered what combining the two would look like, resulting in Link’s quest to collect Tears of Light across provinces.” (Hyrule Encyclopedia 279.) Beyond serving as an important precedent for Skyward Sword – which would apply this philosophy to its entire level design – the Tears of Light do a good job at reframing Hyrule as a geographically cohesive world.

Twilight Princess’ Hyrule is divided into four main provinces (Ordona, Faron, Eldin, Lanayru) with the Tears of Light guiding players through each region. In terms of world-building, this is actually quite important. The kingdom was always structured into major areas, but TP’s interpretation is truer to life. It also makes for a more compelling overworld that Breath of the Wild would structure even further. Hyrule is larger than ever before, and by necessity at that.

“I feel that with a generation accustomed to watching epic films like Lord of the Rings, when you want to design a convincing world, that sort of vast scale becomes necessary.”

– Eiji Aonuma

Hyrule is a kingdom filled with diverse cultures and ecosystems that demand grandeur. Twilight Princess commits to its scope by carving out one of the densest open worlds in the series. Attempting to traverse the entire country by foot is an exercise in futility, so much so that Epona is fully unlocked before the second dungeon. Playing up Hyrule’s scale does mean utilizing more empty space than usual, but Epona controls so smoothly where it’s honestly more fun taking the extra minute to ride somewhere instead of teleporting. Curiously, Epona’s controls were reworked in Twilight Princess HD, making steering far more awkward in the process.

While you need Epona to practically traverse Hyrule, there are a number of reasons to explore on foot. Aside from the Heart Pieces typical to any Zelda game, multiple side quests make use of the overworld. One of the most prominent is the Golden Bug quest. Agitha in Castle Town is throwing a party for all the Golden Bugs in the region, tasking Link with making sure they get to her. There are 24 Golden Bugs altogether, two in every major area in the overworld. The Bugs are very reminiscent of the Gold Skulltula Tokens from Ocarina of Time, but they’re implemented much better.

For one, every Golden Bug can be found by the midway point – rewarding early game exploration considerably. Golden Bugs are generally better hidden than Gold Skulltula, as well. Some bugs are tucked away in ingenious hiding places but are never so off the path where they’re frustrating to track down. Golden Bugs glimmer brightly in the night, shining as the sun, sets. They have a faint glow around them at all times, but the light from the sun helps Golden Bugs blend into their surroundings during the day. Golden Bugs also play a distinct jingle whenever one’s nearby, keeping exploration focused.

Rounding out the 24 Golden Bugs are 60 Poe Souls lurking across Hyrule and inside of mid-game dungeons. You only need to find 20 for the fourth bottle (the only worthwhile reward for the side quest,) but the Poes are fun to hunt down and make explicit use of Wolf Link. Poes can only be fought when “Sensed,” an ability Wolf Link has to hone in on key visual details (imagine a primitive version of Detective Mode from the Batman: Arkham games.) Poes are Twilight Princess’ main way of keeping Wolf Link an active part of the gameplay loop once Hyrule is fully liberated from Twilight’s influence, but they only show up at night; and this is the first 3D Zelda where players can’t manually change the time of day.

For what it’s worth, this isn’t strictly a bad thing. You have no control over the passage of time – which affects which shops are open, who you can talk to, and what you can do at any given moment – but that just lends the sense that Hyrule is a real world. Day and night last a reasonable amount of time, making nightfall or sunrise significant unlike in other Zelda games (save Majora’s Mask.) This also keeps Poe hunts tense as you only have so much time on a single night to track down ghosts. It’s at the expense of convenience, but convenient gameplay isn’t always compelling gameplay. The Poe hunt at least offers a variation on the Gold Skulltula side quest while giving night purpose.

Beyond traditional side quests, Twilight Princess’ Hyrule is full of hidden grottos and a surprising amount of mini-dungeons. Hidden grottos are burrowed into by Wolf Link with puzzles & combat set-pieces typically designed around Human Link. Mini-dungeons are designed almost entirely around Human Link, with Wolf Link relegated to Poe encounters. Instead, the focus is on putting some of the game’s lesser-used items to work. The Lantern Caverns are two dark mazes that require the Lantern to navigate through; the Bridge of Eldin Cavern makes creative use of the Iron Boots’ magnetic properties; and the Ice Block Cavern uses the Ball & Chain as a gate check for the hardest block puzzles in the game.

The only mini-dungeon primarily focused on combat, the Cave of Ordeals is the most substantial. The Cave is a 50-floor gauntlet that makes use of all of Link’s techniques and items. While the Cave of Ordeals can be entered mid-game, it’s a test of a player’s mastery of Twilight Princess’ combat. As a result, the difficulty is considerably higher than anywhere else in-game and enemies are appropriately aggressive. Action, in general, is faster-paced than previous 3D Zeldas, and the UI has been redesigned to downplay menu time. All items are selectable from a ring menu that seamlessly opens & closes during gameplay. This makes selecting an item a fluid process that wastes little game time.

Twilight Princess further mitigates menu time by playing up what Link can do with his sword. Swordplay loses The Wind Waker’s parrying in favor of a more involved gameplay loop. Like in The Minish Cap, Link learns several techniques over the course of the game. The Hero of Twilight’s direct ancestor (implied to be the Hero of Time from Ocarina of Time,) the Hero’s Shade teaches Link Hidden Skills which greatly expand his skill set. Along with offering Link a training arc, the Hero’s Shade only makes combat better. Hidden Skills change how The Legend of Zelda is played in 3D, giving players a wide variety of options at any given opportunity.

“You may be destined to become the hero of legend…but your current power would disgrace the proud green of the hero’s tunic you wear.”

– The Hero’s Shade in his first interaction with Link.

The Shield Attack weaponizes defensive play by allowing Link to deflect arrows & magic while creating openings that can be exploited with the Helm Splitter – a vertical somersault that attacks enemies from above. The Back Slice turns Link’s side dodge into a roll that loops around enemies to strike from behind, the Jump Strike is the Jump Attack’s answer to the Spin Attack, and the Great Spin powers up the Spin Attack even further. Shigeru Miyamoto was such a fan of the Ending Blow – Link’s killing move – that he personally requested the technique be mandatorily learned first so it could be an inherent part of the player’s skill set.

Arguably more important than Hidden Skills, Twilight Princess reworks the combo system. Neither Ocarina of Time or Majora’s Mask allowed Link to connect full combos on enemies. Invincibility frames would prevent at least one hit from landing, keeping players from stunning enemies in place. The Wind Waker revamped combat so that full combos wouldn’t kill most enemies while limiting their use by emphasizing parrying. Twilight Princess encourages constant combos by comparison. Enemies no longer have invincibility frames mid-combo, allowing Link to chain together lengthy attacks while keeping them stunlocked.

Swordplay is immensely satisfying and all of Link’s abilities make it easy to have a solution for any problem; which in itself raises issues. Twilight Princess’ gameplay is just too easy. The Cave of Ordeals is the exception, not the rule, and most of the game requires little to no mechanical mastery on the player’s part. Late game enemies do wear armor to combat this, but they never deal enough damage to be an actual threat. The level design also tries to harden the curve by making Link’s sword react to walls and anything it hits, giving directional inputs actual gameplay purpose. Fighting in a narrow cave? Make sure you stab forward. It’s not enough to make Twilight Princess challenging (& the HD remake outright removes this feature,) but it’s a dash of realism that gives combat a smidge more depth.

Wolf combat is even easier than swordplay. Wolf Link has no real sense of progression like the Hidden Skills. The only ability players unlock is a charge attack which kills most enemies in a single hit. Fighting as Wolf Link is fun enough and has a strategic rhythm, but the fact most enemies die so quickly makes combat hard to enjoy. Not helping matters is how few combat challenges there are designed around Wolf Link. With the exception of a mini-boss in Twilight Lanayru, Wolf Link’s main purpose is sniffing around, platforming via Midna, and hunting Poes.

Where traditional gameplay skews too easy, horseback combat is balanced surprisingly well – to the point where it’s a genuine shame there isn’t more mandatory horseplay. Along with being able to fire the bow on horseback, Link can now use his sword while riding Epona. Not just that, he can quickly dismount into action and do a proper Spin Attack while riding. Enemies on horseback are extremely aggressive, often shooting fire arrows from behind and coming after Link in packs. They don’t let up either, forcing a confrontation. While Epona can run over any enemies on foot, Bulblins riding mounts have to either be cut down with the sword or sniped with arrows. As chaotic as they can get, Twilight Princess’ horse battles are always thrilling.

It’s no surprise Epona’s been given so much mechanical care, as this was the natural next step coming off of Ocarina of Time and Majora’s Mask. Simply being able to swing a sword while riding adds another layer to gameplay. Outside of early battles against King Bulblin and the final boss, however, Epona doesn’t get enough attention. Players can comfortably explore Hyrule as Wolf Link should they so choose, warping wherever they need to go past the halfway point; which is disappointing considering Epona’s influence on development. The whole reason The Wind Waker 2 doesn’t exist was to accommodate gameplay on horseback, after all. Epona plays enough of a gameplay role where she almost demands an entire dungeon just to do her mechanical justice.

This is not to say that Twilight Princess is lacking in dungeons, far from it. In regards to both quality and quantity, dungeon design may be where TP shines brightest. There are no missed opportunities, no hiccups souring the experience, and no mechanical oversights that distract from otherwise good game design. These are simply some of the best dungeons in The Legend of Zelda, with no weak links in the roster. Any dungeon can be pointed to as an example of great puzzle design or environmental storytelling, but Arbiter’s Grounds is almost in a league of its own conceptually.

Arbiter’s Grounds is a temple deep in Gerudo Desert that served as the intended execution ground for Ganondorf following the unraveling of his attempted coup on Hyrule. The first half of the dungeon makes heavy use of Wolf Link while remixing the Forest Temple Poe hunt from Ocarina of Time. This time, three of the four Poes can be hunted down in any order, giving the dungeon non-linearity. The second half, hands players the Spinner – a top Link spins on top of that he can use to grind on rails. Jumping from rail to rail while dodging blade traps gives Arbiter’s Grounds a very unique tension.

With no natural light inside the dungeon, Arbiter’s Grounds is almost pitch black. What flames there are burn bright blue & orange against a dark color palette. This encourages players to use their Lantern to light the way through a sense of foreboding. Unlike most dungeons in the game, Arbiter’s Grounds doesn’t end with a pathetically easy boss fight. By virtue of downplaying the sword’s effectiveness, Stallord is a genuine challenge. He can only be damaged with the Spinner, which requires solid reflexes to maneuver. That Zant personally revives Stallord for the battle adds another layer to the spike in difficulty.

The Arbiter’s Grounds are also a narrative turning point, especially for Zant. Link & Midna enter the dungeon with the intention of using the Mirror of Twilight to enter the Twilight Realm and defeat the Usurper King. Instead, they find that Zant’s already shattered the mirror so that Midna can’t come to confront him. Zant is a coward who hides behind a mask. All his confidence is put on, given to him by Ganondorf. He shatters the Mirror of Twilight and then spends the rest of the game hiding. One failure is enough to send Zant running for the hills. Zant is not a badass. Zant is a sore loser. And that is exactly why he’s such a captivating villain.

Zant is devout to a fault, wholeheartedly accepting that Ganondorf is his God. When Link & Midna fail to succumb to Ganondorf’s magic, Zant waits for divine interference that never comes – in turn shattering his own faith and mind. This comes to a head in the game’s penultimate dungeon, the Palace of Twilight. After reassembling the Mirror, Link & Midna head into the Twilight Realm. From hearing the disfigured bodies of the Twili to powering up the Master Sword with Sol, the Palace of Twice feels like the culmination of everything you’ve done narratively.

Atmospherically, the Palace of Twilight is a tour de force. The sky is a beautiful miasma of black, purple, pink, and gold. The architecture is as alien as it is futuristic, unlike anything in Hyrule. Dark fog forcibly turns Link back into a wolf whenever he passes through it, and Zant’s Hands (TP’s version of Wall Masters) build up some of the most palpable tension in the series by stalking you from room to room. Zant’s Hand will only relent once it takes back the Sol Link has stolen, with several puzzles requiring players to leave the Sol unattended while they make a path. The rising tension makes the sight of the twilight sky all the more refreshing and sets the stage for the fight against Zant.

Zant’s boss battle is a six-phase confrontation chronicling his mental breakdown. The music gets more chaotic, his AI becomes erratic, and Zant goes from telegraphing clear attacks to wildly striking Link in faint defiance. His first five forms are all lifted from earlier bosses in the game, showing how Zant relies on others’ powers even in the face of certain defeat. The only time he fights as himself is when he’s absolutely desperate, at which point he’s already lost. Zant’s demise is pitiful, but fittingly so. This isn’t the end of the game, though. The Palace of Twilight only is Twilight Princess’ faux finale. Zant’s defeat actually culminates in the formal return of Ganondorf, a rather bold twist after bringing the story to its logical conclusion.

Twilight Princess’ story was written by Aya Kyogoku, the first credited female writer on The Legend of Zelda’s staff, and her approach to storytelling is far more hands-on than in previous games. The first half is very focused and narratively dense. Ordon Village gets a lot of unique dialogue for its villagers, and care is given to establishing Link’s relationship with the supporting cast in order to better define his motivations. The first three dungeons are given build up comparable to Majora’s Mask. The Tears of Light set-pieces establish stakes – both narratively and gameplay – while the subsequent Human Link set-pieces formally introduce him to NPCs while giving him the opportunity to act as a genuine hero.

There are multiple set pieces independent of dungeons – like Link fighting King Bulblin on the Bridge of Eldin to rescue Colin or escorting Ilia & Telma to Kakariko Village while enemies rush their wagon. These scenarios flesh out the world, give Link a recognizable connection to the cast and allow a natural bond to form between Link & Midna. The storytelling in this portion of the game is also particularly inspired, flipping Zelda conventions on their head.

After the third dungeon, Zant soundly defeats Link & Minda, nearly killing them both. Princess Zelda is forced to give her life to keep Midna alive and Link seeks out the Master Sword, not as a means to defeat Zant, but to restore his cursed body back to normal. Getting to the Master Sword is a lengthy process, but transforming back into a human feels earned because the game takes the time to establish proper narrative stakes. The story manages to keep this momentum going up until Arbiter’s Grounds where the plot is put on hold for dungeoneering.

It’s not that the second half of Twilight Princess’ story is bad, it’s just that the first 15 hours are front-loaded with strong narrative set pieces and emotional storytelling. The back half takes a very hands-off approach, letting the story play out in the background with set-pieces almost entirely action-based. Restoring Ilia’s amnesia is the only real bit of emotional plotting between Arbiter’s Grounds & the City in the Sky. Climbing Snow Peak, playing tag with Skull Kid in the Lost Woods, and the shootout in the Hidden Village are all fun gameplay moments, but they lack the emotional weight that defined the first half.

Hyrule already feels saved and the stakes come off hazy. That’s not a bad thing in itself, though, and what narrative focus present is at least put on Link & Midna’s growing relationship. Gameplay is the story, especially in Zelda (and it should be pointed out that Ocarina of Time takes this very same approach with its second half) but it’s a shame that all the great character work from the first half is ostensibly put on pause. It isn’t until Link & Midna invade the Twilight Realm that the plot picks back up. Even then, there are problems heading into the last act. Everything leading into and inside of the Palace of Twilight is top-notch. Everything after is another matter entirely.

“Honestly, even now I wish we could push back the release date another month…”

– Aya Kyogoku, one month before Twilight Princess’ release

In terms of The Legend of Zelda’s mythology, Twilight Princess’ finale is an epic confrontation between Link, Princess Zelda, and Ganondorf in their most dramatic showdown yet. In the context of Twilight Princess’ actual narrative, this is a battle between three complete strangers to alter the course of history in a story where only Link is really relevant. There’s certainly something to be analyzed & appreciated about this distinction, but there’s a disconnect after Twilight Princess spent so much time developing its cast.

It’s easy to point at Ganondorf as the issue here, but he’s actually an important asset to Zant’s arc. From Zant’s perspective, the two share a mutualistic relationship that Ganondorf betrays – in turn losing what “Godhood” he had in Zant’s eyes. His death is symbolized by Zant snapping his neck, showcasing that the Usurper King lived on in Ganondorf while asserting himself against the God who led him astray. The real problem is Zelda herself, whose sacrifice earlier in the game is abruptly treated as anything but.

Inside the Palace of Twilight, Midna off-hand mentions that defeating Zant might resurrect Zelda, as if she didn’t give her life just 15 hours earlier in-game. When killing Zant doesn’t reverse his magic, reviving Zelda becomes Link & Midna’s main motivation to defeat Ganon. Midna repaying Zelda’s sacrifice by bringing her back to life does show how much she’s grown throughout the story, yet the logic behind Midna wanting to bring Zelda back simply isn’t telegraphed correctly – or at all, really. Aya Kyogoku told Satoru Iwata that she was making script changes up to the last minute, even wanting more time to work on the story. Taking one look at Zelda’s role in the finale, it’s not hard to see why.

Worse is that Zelda’s reintroduction pushes Midna out of the plot. Link teams up with a princess he’s spent minutes around for the final boss rather than the partner he shares a kindred bond with. Zelda superseding Midna’s role lacks the build-up, context, & relevance of Ganondorf usurping Zant. It’s fan service in a story that accepted Zelda as an ancillary figure; and unlike with Ganondorf, there’s no thematic value to her late-game inclusion. That said, at least Zelda’s reintroduction bolsters Midna’s arc by paving the way towards an otherwise fulfilling ending.

In spite of the finale’s fumblings, Twilight Princess ultimately tells an endearing story that’s carried by Link, Midna, and the connection they forge. Both characters are turned into beasts against their will, but they hold onto their humanity for what they believe is right. Midna is brash and rude, but she eventually wants to protect Hyrule from Twilight’s influence. Link’s been forced into a fight that’s not his and could have comfortably gone home after restoring his body with the Master Sword, but he never leaves Midna’s side.

“Even though he’s the player’s character, he comes with his own personality, which sounds a bit strange, but I think that his uniqueness probably became apparent right after Miyamoto-san had him throw that goat!”

– Eiji Aonuma

Link in Twilight Princess is a simple farm boy who has no political stakes in the war between Hyrule and the Twilight Realm. Nonetheless, he fights tooth & nail to save both lands from tyranny. His journey is motivated by personal reasons – saving Ilia and the kids – but he refuses to stop fighting on Midna’s behalf. Link is an outsider to the world around him, but that’s what makes him an ideal hero. The script makes a point of highlighting Link as a genuinely selfless & caring character. He’s relatively flat, but Link’s representation of true heroism is exactly what inspires Midna’s development.

Midna and Link’s relationship is the heart of Twilight Princess. A victim of Zant who’s forced to hide behind a mask, Midna is understandably bitter at the start of the game. Midna’s royal life has been uprooted, she’s lost her kingdom to a certified lunatic, and the only hope she has of saving her home lies in the paws of a country bumpin who’s been turned into a wolf. Adventuring with Link changes her, as his experience leaves a subtle impact on Midna’s development. Link’s selfless resolve helps Midna realize that Hyrule & the Twilight Realm are an equilibrium, and to save one means saving the other. Midna steps out of the shadows to become a hero in the light of Link’s heroism.

All the care given to characterizing Midna and her relationship with Link adds weight to removing her from the finale. The fact Midna survives is a genuine relief, and the possibility of potentially losing her makes the final battle between Link and Ganondorf personal. True to Twilight Princess, however, their reunion is bittersweet. Midna ends the game by shattering the Mirror linking Hyrule and the Twilight Realm, preventing anyone like Ganondorf or Zant from abusing Twilight’s power again. Midna permanently severing her connection to Link is a heartbreaking moment, but it’s driven by a selflessness that brings her arc to a close. As dawn breaks, the Twilight Princess bids goodbye to her other half.

At its core, Twilight Princess’ storytelling is reflective of the same ambition that bleeds through the entire game. It doesn’t always work, but when it does, there are moments of genius you can’t get elsewhere. In a way, that describes the Nintendo GameCube’s legacy just as much as Twilight Princess’. The GameCube’s ambitions didn’t necessarily pay off with a mass audience, but the console is home to one of Nintendo’s most creative line-ups of video games. Twilight Princess is the culmination of everything Nintendo’s developers learned during the 6th generation of gaming, and likewise a rejection of the worst qualities that defined its contemporaries – long load times, thoughtless art direction, and realism at the expense of game design.

Satoru Iwata once said that the world was expecting the greatest Zelda game ever made. That’s not Twilight Princess, and it, unfortunately, wasn’t going to be. Eiji Aonuma spent too much time working on The Minish Cap before fine-tuning TP, Aya Kyogoku was never satisfied with her final story, and the Wii port uprooted the game’s direction. But that doesn’t stop Twilight Princess from fleshing out Hyrule, mastering dungeon design, and fine-tuning swordplay to perfection. Every game is mired by missed opportunities and unmet expectations, that’s just the nature of art. Flaws & all, The Legend of Zelda: Twilight Princess marks a thoughtful end to an era – a somber goodbye to the GameCube scored to distorted tones and drowned in dusk.

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks agoDon’t Watch These 5 Fantasy Anime… Unless You Want to Be Obsessed

-

Culture3 weeks ago

Culture3 weeks agoMultiplayer Online Gaming Communities Connect Players Across International Borders

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks ago“Even if it’s used a little, it’s fine”: Demon Slayer Star Shrugs Off AI Threat

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoBest Cross-Platform Games for PC, PS5, Xbox, and Switch

-

Game Reviews3 weeks ago

Game Reviews3 weeks agoHow Overcooked! 2 Made Ruining Friendships Fun

-

Guides4 weeks ago

Guides4 weeks agoMaking Gold in WoW: Smart, Steady, and Enjoyable

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks ago8 Video Games That Gradually Get Harder

-

Game Reviews3 weeks ago

Game Reviews3 weeks agoHow Persona 5 Royal Critiques the Cult of Success

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks agoDon’t Miss This: Tokyo Revengers’ ‘Three Titans’ Arc Is What Fans Have Waited For!

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoThe End Is Near! Demon Slayer’s Final Arc Trailer Hints at a Battle of Legends

-

Guides2 weeks ago

Guides2 weeks agoHow to buy games on Steam without a credit card

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoSleep Meditation Music: The Key to Unwinding