Features

Metroid: Other M Critique and Reevaluation

Other M’s is not the worst game Nintendo has ever put out, but it certainly did not deserve as much critical praise as it received.

“No objections, right, Lady?”

Metroid is one of the most premier franchises in gaming, sitting comfortably alongside the likes of Super Mario and The Legend of Zelda. Unlike other Nintendo powerhouses, however, Metroid has never been as stable. The franchise’s releases have always been limited. Retro Studios’ Prime sub-series helped pad out the series’ library, but the fact of the matter is that there are only five mainline Metroid games including Dread and not counting remakes. Metroid does not release with the same frequency as Nintendo’s other AAA franchises, often skipping out on entire generations if the stars fail to align. This is a philosophy that has kept Metroid’s reputation pristine for the most part, but also demanded that the series go on a lengthy hiatus following Other M’s controversial release.

Metroid: Other M was not rushed, does not have much in the way of cut content, and is one of the most technically sound games on the Wii. Nintendo even approached Team Ninja of Ninja Gaiden fame to work on the combat as director Yoshio Sakamoto’s own team was inexperienced at developing games in 3D environments. While Other M launched to mostly positive reviews (holding a respectable 79 critic score on Metacritic), the game’s reputation with most series fans has never been stellar. Other M holds a 6.7 user score on Metacritic, a whopping D rank on the Japanese website mk2, and was heavily discounted to just $6.99 only a year after its North American release (almost certainly to combat bad word of mouth).

Not helping matters is that Other M ushered in a near-decade-long hiatus, a fact that only built resentment towards the game over time. In a world where Metroid Prime 4 and the long-awaited Dread are actually on the horizon, Other M almost begs for reexamination. Critics of the era clearly saw something in the title that fans did not. Is Other M’s negative reputation still warranted? Did Metroid really need to go on such a long hiatus following its release? What is it that makes M:OM so divisive to begin with? Most importantly, is Other M even worth playing?

Between Super, the Prime sub-series, and the GBA duology, Metroid regularly knocks control schemes out of the park. Metroid controls are responsive with high-skill ceilings that reward players who take the time to experiment or master the core mechanics. Level design carefully considers what you can do at any given time, with Super and Zero Mission allowing you to sequence break depending on your skillset. Single wall jumping and chaining bomb jumps can be tricky, but comfortable controls keep trial and error fun. Other M pivots hard from its predecessors’ comfortabilities by relegating a rather complex control scheme to a single Wii Remote. Although ambitious, the end result undermines M:OM’s gameplay.

Other M’s control scheme was directly inspired by the NES’. Yoshio Sakamoto’s goal was to create an action Metroid that would appeal to casual gamers, so as not to overwhelm them with a control layout where every button does something unique. Sakamoto’s logic makes enough sense, but the problem is that M:OM is 2D and the NES controller was never meant for 3D spaces. Frantically controlling Samus in a three-dimensional environment demands an analog stick, not the D-Pad. Other M is what the Nintendo 64 would have felt like if Nintendo just kept the SNES controller as is. Always be grateful this did not happen.

Controls are simple in theory. Samus is almost always controlled by holding the Wiimote horizontally. The D-Pad moves, A activates the Morph Ball, Plus opens the menu, 1 shoots, and 2 jumps. Pointing the Wiimote towards the screen reorients your perspective from third to first person. A fires your beam and B locks onto targets. Aiming in first-person is the only way to use Missiles and can only be done by locking on. A lack of buttons on the Wiimote leads to quite a lot of automation, as well. You simply need to walk into a Save Station to save or walk up to a computer to use it. Jumping on top of certain enemies with your beam charged up will trigger a unique attack. Take Downs let you finish off stunned enemies by just walking into them.

Samus automatically locks onto targets during third-person combat, meaning you never need to aim directionally. Tapping any direction on the D-Pad before getting hit triggers Samus’ Sense Move, a quick dodge that fully charges up her Charge Shots and lets you unleash a devastating attack in a split second. You can use Sense Move in first-person by turning the Wiimote right before an attack connects. Timing for Sense Move is extremely generous, making it virtually impossible to mess up. Tilting the Wiimote vertically without pointing at the screen and then holding down A allows Samus to restock her Missile ammo. You can also do the same to restore one whole Energy Tank’s worth of health whenever Samus is in critical condition.

In execution, Other M’s controls leave much to be desired. Moving Samus with the D-Pad is downright frustrating and never feels quite natural. Needing to quickly jump between third and first-person by physically pointing the Wiimote at the screen is a headache and a half during some confrontations. The fact Samus cannot move at all in first-person makes you a sitting duck without Sense Move. Even then, mastering Sense Move in first-person completely trivializes battles since missiles are so powerful. Bombs have a slight delay, a wrong turn (or a fat thumb) can throw off Samus’ auto-aim, and the Wiimote’s signature comfortability is all but lost trying to jam a 21st-century action game’s worth of mechanics into a control scheme dating back to 1983.

Limitations often bolster art, but there is a fundamental difference between overcoming your natural limits and limiting yourself for the sport of it. The former is inspiring while the latter is ambitious — and misguidedly so in the case of Other M. The NES style control scheme simply does not match the 2.5D level design at play, resulting in an experience that is painfully at odds with itself. M:OM is set on the Bottle Ship, an abandoned Federation facility dedicated to researching bioweapons. Immediately, the Bottle Ship draws comparisons to Fusion’s BSL that make it come off derivative. This is only compounded by the fact that the Bottle Ship is also broken up into sectors (albeit three instead of six) designed to emulate different ecosystems.

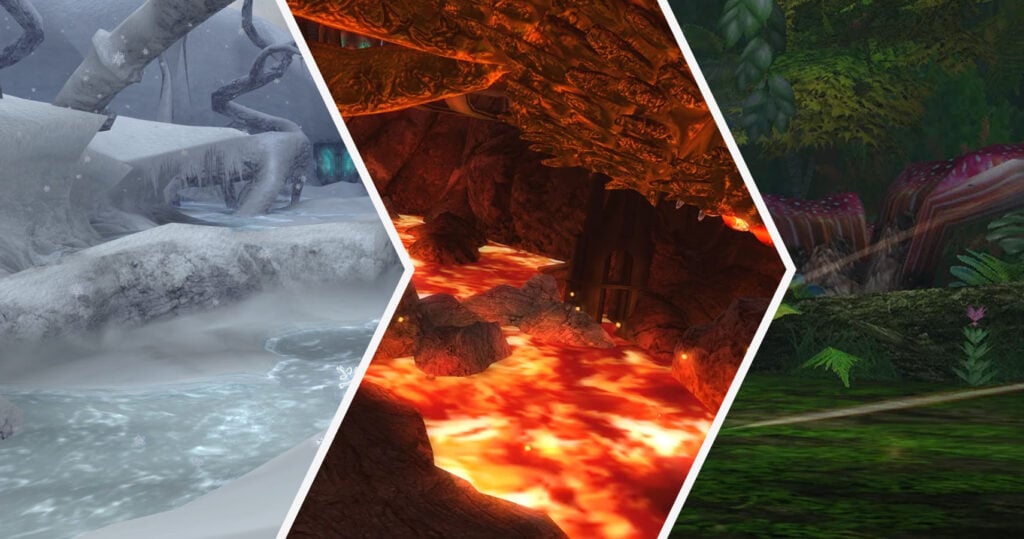

The Bottle Ship’s three main sectors are holographic environments that Samus can activate on and off with terminals. Their simulated visuals occasionally ripple to show the Bottle Ship’s features, but each area generally sticks to one theme. Sector 1 is the Biosphere, an artificial jungle filled with greenery and exotic animal life; Sector 2 is the Cryosphere, a sub-zero habitat covered in ice, snow, and water; and Sector 3 is the Pyrosphere, an extremely hot Norfair-esque region flooded with actual lava for some reason. The three sectors are connected by a central elevator in the Main Sector, which is the closest thing Other M has to a hub. The Bottle Ship is rounded out by Sector Zero and the Bioweapons Research Center. The former is built up as the final area but never visited while the latter is mainly an arena for the final boss.

Other M’s settings look nice and are colorful, but they are also painfully generic. The grass/water/fire motif is already a staple of Mario and Zelda, so much so that virtually every major game in those series features some variation on a grass, water, and fire level. Metroid always avoided this with its alien set pieces. Super has a jungle, but it’s unlike anything found on Earth. Norfair is not just a volcano, but home to ancient ruins that speak to a lost culture. Fusion makes sure its most generic areas are still visually unique by making BSL’s mechanical structure clash with each sector’s flora and fauna. Other M is so focused on making each sector look lush that Metroid’s alien personality is sapped dry. All that’s left are the grass, fire, and water stages you see in virtually every Nintendo game.

Level design is nothing to write home about either, if not outright bad most of the time. The Bottle Ship is hallway after hallway with little of interest to see or do. Sectors sometimes sprawl out into open fields, but Samus’ controls are not suited for 3D environments. What few platforming sections there are also suffer from the D-Pad’s unreliability and a lack of proper depth perception/camera control. You are almost always guided. Save points place waypoints on your map and cannot be avoided. A yellow arrow tells you which direction to move in your mini-map. The Bottle Ship regularly locks doors behind Samus so you can only push forward. Fusion proves that a linear Metroid can work well, but M:OM lacks intelligent puzzles, engaging platforming, and meaningful navigation.

Every now and then, gameplay swaps to an over-the-shoulder perspective where Samus’ movement becomes heavily restricted. These segments are meant to build tension — often before a cutscene or boss fight — but the fact you can only walk means there can never be anything dangerous around the corner. Worse, slowly walking through the Bottle Ship as Samus is an utter drag. There is nothing to engage with mechanically and the audience does not gain a deeper sense of immersion by suddenly changing the camera angle. As annoying as these over-the-shoulder stretches are, they are nothing compared to Other M’s pixel hunts. During certain cutscenes, Samus will be locked into first-person and you will be forced to examine anything suspicious in the scenery.

This sounds harmless enough on paper, but a lack of context and bland art direction make it very difficult to figure out what you’re even looking for half the time. For a story as verbose as Other M’s, the script is jarringly content depriving you of critical information during these pixel hunts. Your targets are often so small and inconspicuous that you often need to defy reason just to make progress. One hunt requires Samus to turn around completely from where her fellow Federation soldiers are looking. All logic and context dictates that you should examine what is directly ahead of you, but Samus actually needs to turn around unprompted and find a green pool of blood on a green field. M:OM lacks the necessary telegraphs for its “puzzles” to work.

One of the best parts of Metroid is finding upgrades and watching Samus get stronger over the course of the game. Other M makes some major changes to the system. You can still find Energy Tanks and Missile expansions in the overworld, but the map now tells you exactly where in the room each upgrade is. Not just that, major upgrades like the Varia Suit and Super Missiles must now be authorized by Samus’ Commanding Officer, Adam Malkovich. Adam actively monitors Samus’ situation, determining when to turn on specific upgrades depending on the situation. Regardless of how this is handled narratively (poorly), Other M gains nothing from ripping away progression’s agency. Adam letting you use an upgrade you theoretically already have is inherently unsatisfying. Compare that to the thrill of finding the exact upgrade you need to progress in a game like Super.

The fact that upgrades unlock in a set order as part of the story means you can never sequence break. Fusion does this, as well, but BSL’s level design counters its linearities with well-kept secrets and a complex layout. The Bottle Ship is simple to a fault, funneling you wherever you need to go at all times. You do not need to keep your eye out for upgrades or even bother studying your surroundings. Other M gives Samus everything she needs when she needs it, streamlining a core concept that makes Metroid fun to begin with.

The best thing that can be said about Other M is that battles are flashy. Samus is very stylish in action, executing enemies in increasingly creative ways through her Take Downs. Enemy models are detailed and actually feature clever telegraphs that require a keen eye for observation. With a better control scheme, gunning down enemies in M:OM could have been quite fun. That said, there are still fundamental issues with combat. For starters, Other M is an action game without combos or attack chaining. The best you can do is button spam your beam and charge up shots in-between Sense Moves. There is next to no mechanical depth at play and that is a crying shame for Metroid.

As far as presentation goes, Other M is a mixed bag. Character models look great and most of the lighting is decent throughout, but textures tend to be choppy and the overall aesthetic falls on the dull side. Cinematography is generally engaging — particularly for any action-heavy sequences — but Kuniaki Haishima’s score is a series low point, often underscoring key moments and relying on too much ambiance. M:OM’s best tracks are arrangements of franchise staples. Besides Haishima’s lackluster music, the English voice direction is borderline abysmal. Corruption also featured voice acting for every line of dialogue, but it was reserved and restrained. Samus never stops talking in Other M and Jessica Erin Martin’s monotone delivery makes it difficult to stay invested.

Other M fancies itself a character study of Samus Aran, examining her backstory with the Galactic Federation and relationship with Adam Malkovich — a former Commanding Officer whose consciousness would be the basis for the Adam AI in Fusion. This is material perfectly suited for a prequel, but M:OM instead takes place immediately after the events of Super. Haunted by the baby Metroid’s sacrifice, Samus spends most of the story in a deeply introspective state. Much of the script centers around the relationship between a parent and child. First framed through Samus’ relationship with the baby and then flipped when she reunites with Adam at the Bottle Ship. Samus monologues about her feelings, the impact Adam has had on her, and her own agency. These are all interesting ideas, but the execution is laughable.

Samus narrates her every waking thought, leaving absolutely nothing to subtext and at times even describing what is happening as if Other M were a book. Her relationship with Adam is totally toxic and almost ruins his AI’s appearance in Fusion. Samus and Adam have a strained relationship on account of her leaving the Galactic Federation to become a Bounty Hunter, almost mirroring the strained relationship between a parent and their child who leaves home abruptly. Being back in Adam’s presence makes Samus revert to old ways, wanting to prove herself in the eyes of the father she left behind. Samus wants to show Adam that she can be a team player and Adam wastes no time falling back into their old routine.

Adam’s arc ends with him sacrificing his life for Samus, performing an unmistakable act of love that proves how much he actually cares for her. This does not absolve Adam from acting blatantly and consistently abusive, however. Adam is cold, disrespectful, and humorless. He cares about Samus, but does not know how to show affection and goes so far as to literally shoot her in the back before his sacrifice. The notion is that a hard man like Adam helped forge Samus through Hell, but he just comes off like an abuser. The kindest thing Adam does for Samus is die and free her from a relationship that does nothing but weigh her down.

What makes Adam’s presence in the story even stranger is the inclusion of Anthony Higgs, Adam’s point man and an old friend of Samus. Anthony also cares about Samus, but he expresses his feelings in a healthy manner. Anthony goes out of his way to converse with and support Samus throughout the story. Where Adam restricts her, Anthony builds her up. M:OM’s story would have been better if Anthony were Adam and Other M explored a healthy parental relationship instead of a toxic one. They both go so far as to sacrifice themselves to protect Samus (though Anthony manages to survive). Anthony outright shares Adam’s exact defining trait: they both have an affectionately feminine nickname for Samus. Adam calls her “Lady,” Anthony calls her “Princess.”

When it really comes down to it, swapping Adam with Anthony would have only fixed one aspect of Other M’s juvenile script. Samus is not treated like a human woman, somehow even less so than in the games where she barely speaks. Giving an audience access to a character’s thoughts is a double-edged sword. It works in literary mediums, but necessarily in gaming and certainly not without airtight dialogue. Even the plotting is awful and has no real regard for continuity beyond acknowledging Super. Samus infamously has a breakdown fighting Ridley, despite the fact she has fought and killed him a minimum of three times at this point in Metroid’s chronology. The end result is a narrative that punishes anyone emotionally invested in the series.

Even at its absolute best, Metroid: Other M is still held back by its own design philosophies. Yoshio Sakamoto had a very clear vision that ultimately damned the game. Other M’s problems go beyond not playing like a typical Metroid. From the controls to the level design to narrative, nothing coalesces properly. The Wiimote results in what might be the series’ single worst control scheme of no fault of its own. A few well-hidden upgrades are not enough to salvage deeply uninspired level design that cares more about presentation than fun. Humanizing Samus only makes her difficult to like where she was previously one of Nintendo’s strongest protagonists in terms of characterization.

Other M’s is not the worst game Nintendo has ever put out, but it certainly did not deserve as much critical praise as it received. M:OM’s negative reputation is deserved in a lot of ways and Metroid going on such a long hiatus proved to be nothing but a blessing. Samus Returns’ 3DS release featured a stoic Samus, an emphasis on environmental storytelling, and gameplay suited for its hardware. If you can stomach the control scheme, M:OM is worth playing if only out of morbid curiosity. If not, all you’re missing are hand cramps and writing on par with the Star Wars Prequels. Metroid: Other M may not sting as much a decade after its launch, but the game will always be a stain on the franchise’s history.

-

Features4 weeks ago

Features4 weeks agoDon’t Watch These 5 Fantasy Anime… Unless You Want to Be Obsessed

-

Culture3 weeks ago

Culture3 weeks agoMultiplayer Online Gaming Communities Connect Players Across International Borders

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks ago“Even if it’s used a little, it’s fine”: Demon Slayer Star Shrugs Off AI Threat

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoBest Cross-Platform Games for PC, PS5, Xbox, and Switch

-

Game Reviews3 weeks ago

Game Reviews3 weeks agoHow Overcooked! 2 Made Ruining Friendships Fun

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks ago8 Video Games That Gradually Get Harder

-

Game Reviews3 weeks ago

Game Reviews3 weeks agoHow Persona 5 Royal Critiques the Cult of Success

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoThe End Is Near! Demon Slayer’s Final Arc Trailer Hints at a Battle of Legends

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks agoDon’t Miss This: Tokyo Revengers’ ‘Three Titans’ Arc Is What Fans Have Waited For!

-

Guides2 weeks ago

Guides2 weeks agoHow to buy games on Steam without a credit card

-

Uncategorized2 weeks ago

Uncategorized2 weeks agoSleep Meditation Music: The Key to Unwinding

-

Game Reviews1 week ago

Game Reviews1 week agoFinal Fantasy VII Rebirth Review: A Worthy Successor?