Features

Metroid Fusion is a GBA Masterpiece

Just like Super Metroid before it, Metroid Fusion is a 16-bit masterpiece…

Super Metroid set new expectations for the franchise when it launched for the Super Nintendo in 1994. Whereas the first Metroid is an exploration-heavy adventure in a confusing labyrinth and Return of Samus grounded its gameplay with direction conveyed through environmental storytelling, Super is the best of both worlds without feeling derivative. Super Metroid will naturally guide you down an intended path like RoS, but allows you to break away at virtually any point like in M1. This makes for a very replayable game where each playthrough carries unique pacing — the key unifier being that pace in Super Metroid is always player-driven. All the while, Super indulges in a subtle narrative told almost exclusively through visuals.

The rest of the series could have coasted by imitating Super Metroid game after game, but Metroid is a franchise about exploring the unknown. Return of Samus was such a good sequel, specifically because it strived to be more than the original on a handheld. Super Metroid borrows quite a few design concepts from the first Metroid, but never without radically recontextualizing things to fit its own identity. Metroid is an ambitious series at its core, and for the fourth entry to simply follow in Super’s footsteps would be a disservice given how distinct each title in the original trilogy actually is. Metroid 4 always needed to be more than just Super Metroid 2.

Metroid Fusion was released in 2002 for the Game Boy Advance after an eight-year series lull and is not shy about flaunting its status as Super Metroid’s antithesis. Consequently, it is important not to think of Super and Fusion in terms of better or worse as they both approach Metroid from two completely different angles. Where Super Metroid zigs, Metroid Fusion zags. The GBA’s inherent limitations as a handheld also mean that sticking too closely to Super’s foundation would be next to impossible without making major compromises. Rather than risk a legacy rooted in its predecessor’s shadow, Fusion redefines what a Metroid game can be.

There is almost no freedom in Metroid Fusion. The story, now traditionally told through consistent dialogue and cutscenes, is totally linear. Every playthrough will take you through the same areas in the same order. Major upgrades cannot be sequence broken and are tied to bosses, preventing certain secrets from being found until late-game. Rarely will you be allowed to explore at your leisure and, when you can, your only rewards will be Energy Tanks or ammo capacity upgrades for the Missiles and Power Bombs — helpful, but nowhere as fun as finding something like the Varia Suit early.

None of this makes Metroid Fusion bad, though, as the development team was very conscious about the game they were making. When asked why Nintendo chose not to simply port Super Metroid to the GBA in the vein as of A Link to the Past and Super Mario, series director Yoshio Sakamoto said,

“We always try to do something really unprecedented, something people have never played before . . . I know that Metroid always has to grow — we’ve always been challenging [players] with the Metroid games.”

For Metroid to grow in a post-Super world, Fusion needed to tread new ground. Cutscenes flesh out the series’ lore, reveal bits of Samus’ backstory, and elevate the in-game tension whenever the plot veers into horror/thriller territory. Linear level design means puzzles can build off each other organically while the difficulty curve gradually rises instead of dips as you unlock more upgrades. Restricting your ability to fully explore the map until the very end ties into Fusion’s core themes and even gives Samus something of a character arc since the freeform gameplay mirrors her regained narrative agency.

Samus as a character is something Fusion plays with extensively. She is a stoic bounty hunter whose few lines of dialogue up to this point were exclusive to Super’s opening (and only) cutscene. The original trilogy depicts Samus as a hardened figure who can overcome anything. She defeats Mother Brain’s Space Pirates twice over, kills nearly every last Metroid in the Galaxy, and escapes a detonating planet with seconds to spare. Samus probably has the best overall resume as far as Nintendo heroes go, which makes her fate at the start of Fusion all the more shocking.

Metroid 4 opens with Samus crashing her iconic spaceship into an asteroid belt. This is the very first thing you see if you let the title reel play out when the game boots up. There is no context offered until you actually start your playthrough — just the sight of Samus Aran flying into what should be certain death. Instead, a parasitic infection she picked up on SR388 and some Metroid DNA keep her alive at the expense of sealing her inside of her suit. Samus’ opening monologue in the story properly explains that the organic components of her Power Suit attached themselves to her actual body during surgery. For all intents and purposes, Samus is her suit in Fusion.

Coming so close to death leaves Samus particularly introspective. While she won’t do it each time, Samus tends to monologue on long elevator rides. Throughout Fusion, Samus reflects on her disdain for orders (something echoed in the restrictive level design), past adventures, and a former Commanding Officer named Adam Malkovich who had a profound effect on her. Samus goes so far as to name her new ship’s AI “Adam,” developing something of a friendship with him before realizing that the Galactic Federation kept the real Adam’s consciousness around as data. Adam’s presence gives the story a clear arc while adding some tension to the plot. He ultimately comes around, but Adam’s cold candor makes it hard to tell if his allegiances lie with Samus or the Galactic Federation.

The use of body horror to corrupt Samus’ physical appearance is significant for several reasons. Without a doubt an element of pure sexualization to it, but Metroid’s history of depicting Samus in her underwear at the end of games shows that she is comfortable in her own skin. Super Metroid even ends with Samus quite literally letting her hair down if you beat it fast enough. Taking off her Power Suit is how she relaxes, but Fusion turns Samus’ armor into skin. This is her body now, and it is anything but familiar. The new Fusion Suit pushes this lack of familiarity to the extreme.

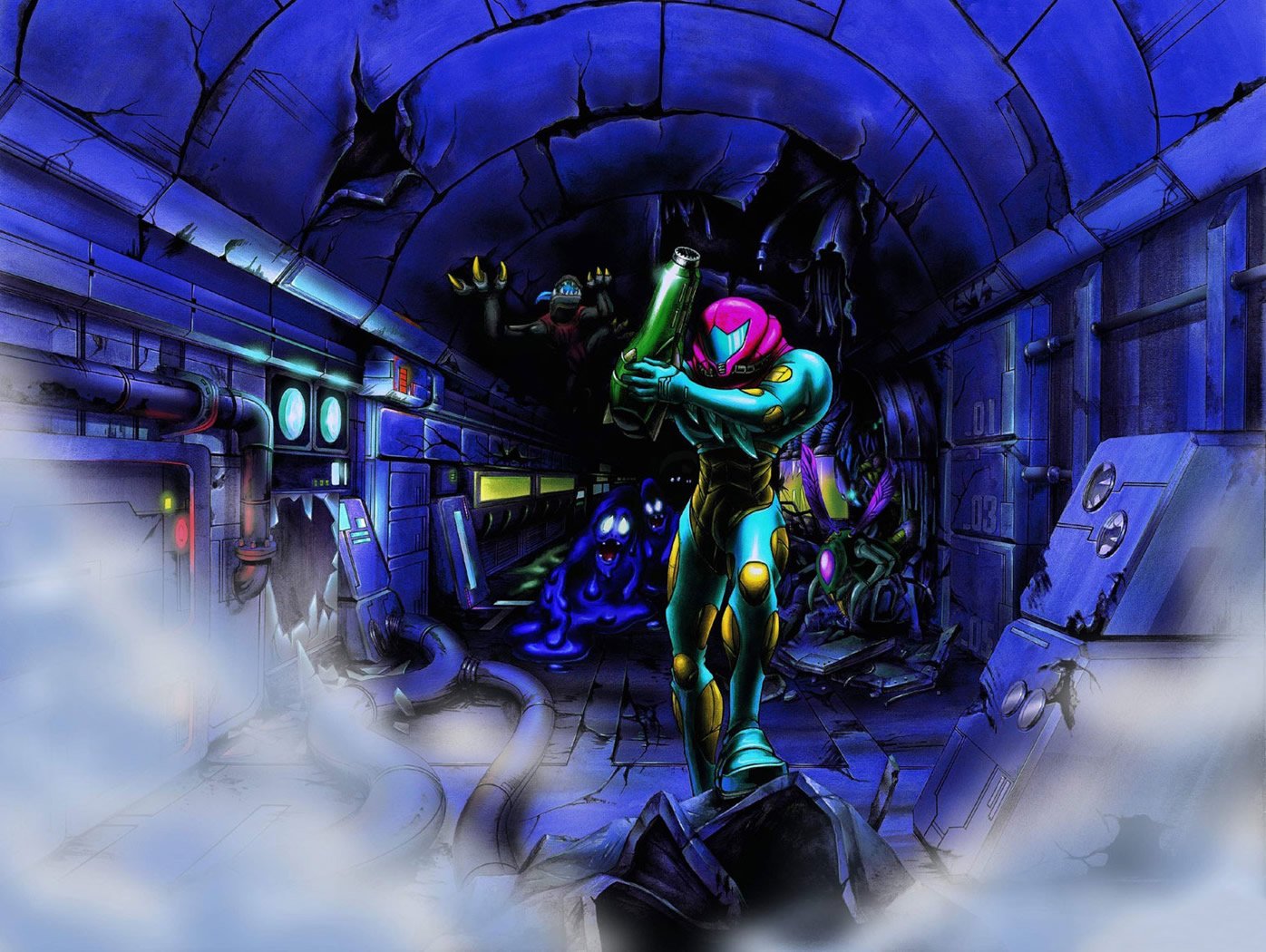

Samus’ signature orange Power Suit is replaced with a garish mix of blue and yellow. With her helmet retaining its usual red coloring, the Fusion Suit’s sleek blue outer frame and yellow plating make Samus look downright alien. Samus being trapped in her armor is paralleled by the level design. Unlike earlier Metroids that took place on hostile planets, Fusion is set in a man-made spaceship: the BSL (Biologic Space Labs) Research Station. BSL floats through outer space, recently had its entire crew killed, and has a clinical aesthetic that clashes with the series’ established atmosphere. Nothing is as it should be.

There is an idea that games should always let you do what you want when you want since this is a form of expression inherent to the medium, but there are several ways to play with control as a concept. Just because a game forces you to play a certain way does not mean that it is failing its medium. Not every game benefits from freedom, and it should not be treated as a hard and fast rule of game design. Samus is working for the Galactic Federation — the largest military organization in the Galaxy — exploring a Federation ship. She cannot afford to explore at her leisure with active monitoring and an AI she needs to rely on just to unlock certain doors. Fusion makes you feel every bit of her restriction, but not to the point where the game stops being fun.

Instead, restriction builds tension and turns BSL into a claustrophobic setting you cannot brute force like Zebes. Being unable to explore freely is disappointing, but the actual level design is tightly crafted and stands out as one of Fusion’s best qualities. Linear progression results in a controlled difficulty curve that prevents you from getting too powerful. Every area you visit will be harder than the last, introducing stronger enemies and advanced platforming challenges that must be overcome with no option of returning later once you have more upgrades. Since you always know where to go and your goal, Fusion maintains a breakneck pace where you never hit an actual dead end.

BSL is a research lab dedicated to studying all kinds of galactic life, dividing specimens into six numbered sectors connected to a central Main Deck. Every room in the station has some practical purpose, making it clear that people were actively working here before Samus’ arrival. The Main Deck functions as a central hub of sorts, but most of the gameplay occurs down in the sectors. Unlike the rest of the lifeless station, each sector is modeled to mirror a different biome — in turn housing unique flora and fauna while featuring more varied environments than seen in previous titles.

Each sector has its own theme, both in regards to aesthetics and gameplay. Sector 1 (SRX) is a recreation of SR388’s natural habitat. SRX shows what Metroid II would have looked like in 16-bit (giving the planet the same treatment Zebes got in Super) while foreshadowing that the Galactic Federation are trying to clone their own Metroids like Mother Brain once did. The sector comprises a straightforward level design with a mix of basic platforming and combat typical for starter areas in Metroids. Sector 2 (TRO) is a tropical region similar to Upper Brinstar. The overrun Jungle clashes with BSL’s mechanical backdrop and serves as an early test of your observational skills. Where SRX guides you naturally, TRO forces you to spot hidden passages in the walls and floor to proceed.

Sector 3 (PYR) is a volcanic/desert-themed research center dedicated to intensely hot ecosystems eerily reminiscent of Norfair. Pools of lava and heatwaves serve as environmental hazards, testing your navigational skills and common sense. The sector is fairly linear on a first visit since Adam specifically tells you to turn around if things get too hot, but the level design compensates with a gauntlet of cleverly placed enemies. The fact several rooms gate Samus out without the Varia Suit teases you with upgrades to return for.

Sector 4 (AQA) is a massive aquarium that looks like a cleaner Maridia the deeper in you go. Broken circuits channel electricity through the water, draining Samus’ health while weighing her down without the Gravity Suit. You cannot let yourself fall in, and basic navigation through AQA demands tight platforming. Lowering the water level changes Sector 4’s focus towards using the Speed Booster and keeping momentum to break through barriers. Sector 5 (ARC) is the first arctic setting in Metroid and the last major area introduced in Fusion. ARC may not serve as the actual final level, but its complex layout filled with hidden pathways makes it more challenging to traverse than other sectors.

Sector 6 (NOC) is an expansive cavern cast in near-total darkness. A soft light glows around Samus while the rest of the scenery is dark. The visual effect is not as prominent on emulators or the DS and 3DS, but NOC makes you pay closer attention to your surroundings. Cold Parasites are also introduced here and rush at Samus, draining her health on contact. You need to run for your life and move strategically until you get the Varia Suit, putting you on the defensive for most of Sector 6. Stopping for even a second can mean getting swarmed to death, fostering a deeper level of tension than other sectors. Interestingly, NOC is actually connected to a secret facility dedicated to cloning Metroids. Sector 6’s dark environment is not just for gameplay variety but an SR388 inspired breeding ground.

As alluded to with ARC, sectors are not visited in their numbered order. Instead, Samus’ first run goes — 1, 2, 4, 3, 6, 5 — while backtracking in the second half has you revisiting — 3, 5, 2, 5, 4, 6, 1 — with trips to the Main Deck serving as a pace breaker. Fusion’s level order is non-negotiable and does not allow for meaningful sequence breaking. Sectors outright lock you inside as part of the story, inherently preventing exploration. Fusion funneling you through the same sectors in the back half keeps the pace moving organically. Maps are limited on a first visit but open up considerably as you unlock more upgrades. You get a chance to revisit everything before the end. Certain sectors are even connected, seamlessly transitioning you into different levels on a few occasions.

Linear level progression leads to tougher puzzles. Metroid generally does a good job at forcing you to think critically about navigation. In a game like Super, getting “stuck” usually means you have a few options: you can come back later, try to sequence break, or figure out the actual problem. In some cases, you never need to actually do what Super expects from you. This could not be more different in Fusion, where getting stuck means figuring out how to move forward.

Lacking freedom helps you learn how to naturally spot “Metroidisms” as each one is introduced to you organically. If the game locks you between two pillars too high to jump over, you stop and bomb every inch of the floor because that is your only option. If you need to explore a sector, but all the doors are locked, look for anything odd in the scenery like suspiciously out-of-place enemies running up the walls and start investigating. Play through Fusion, revisit Super, and marvel at your newly developed awareness. Fusion may lack Super’s freedom, but it opens your eyes to level design nuances by gradually introducing you to harder gameplay concepts at a steady pace.

Where Super introduced a proper map for players to reference, Fusion expands it by actually showing how rooms connect, where doors are located, and sporting a color-coded legend that lets you know which lock types have been activated. The map even distinguishes between which upgrades Samus picked up and the ones you only found. A hollow circle represents an upgrade you failed to pick up, while a bold circle marks a room you found all the upgrades in. This is extremely convenient for 100% completion and makes it so you don’t have to worry about forgetting items you cannot grab right away. Fusion lacks Super’s mini-map, but it ultimately would have resulted in too much screen clutter, so its absence is hardly felt.

In a move that might seem too helpful to series veterans, the map now shows exactly where you need to go with a glowing waypoint. You still need to figure out how to get there yourself, but this fundamentally changes how you approach each area. That said, waypoints are not a bad addition and are appropriate given that Metroid Fusion is a GBA title designed for shorter play sessions. Knowing exactly what you need to do when you boot up your handheld lets, you dedicate shorter play sessions while making reliable progress (which might be another reason why Fusion is so restrictive — linearity simply suits a handheld better than freeform exploration).

Atmospherically, BSL embraces Metroid’s horror flarings with fervor. Some sectors are creepy in their own right — the Nightmare’s shadow looms over ARC and NOC’s darkness fosters paranoia — but Fusion’s fear factor is rooted in X Parasites. In a case of reality kicking in, there are actual consequences to interfering with nature and killing off an entire species due to a perceived threat to mankind. Without any living Metroids left on SR388, their natural prey — the X Parasites — are free to consume everything in sight. X Parasites kill their prey by infecting a host, taking over their nervous system, and then mimicking their appearance once assimilation is complete.

BSL is completely overrun with X Parasites by the time Samus arrives. Virtually every animal and human being on the station has been fully infected if not just outright killed. Killing an enemy does not actually kill an X Parasite but instead frees them to consume a new host. Samus is safe due to the Metroid DNA injected into her during surgery, but the galaxy is otherwise at great risk with X Parasites free to reproduce. This is actually conveyed through gameplay — X Parasites start flocking in large numbers to respawn enemies if you wait long enough, showing that they are essentially unkillable.

Because Samus’ Power Suit is made out of organic material on some level, the parts that were successfully surgically removed succumb to infection. Samus’ iconic orange armor morphs into a twisted version of herself called SA-X (Samus Aran-X), stalking BSL, searching for anything to hunt. SA-X’s kill on sight approach makes her extremely dangerous. In a sense, it puts into perspective just how formidable a bounty hunter Samus actually is. Virtually every encounter with SA-X requires you to run for dear life since fighting back is basically suicide. Adding insult to injury is that SA-X’s sprite is more or less what Samus would look like in Fusion if she retained her suit from Super.

SA-X is why Fusion needs to be so linear in the first place. Restricted gameplay forces you to confront fear head-on. There is a greater emphasis on horror set-pieces than ever before, with SA-X front and center. She has an impactful presence that builds gradually over the course of the story. Just seeing SA-X on-screen is enough to convey that you are in grave danger. It would be next to impossible to pull off this kind of tension without linearity. There needs to be a fear that SA-X can be anywhere, and being railroaded down a set path means you have to confront her in some capacity when she appears.

Encounters with SA-X are actually more scripted than they let on, but she has an intimidating touch. SA-X actively destroys the level design and prevents you from cleanly backtracking, dynamically changing whichever sectors she enters. You can hear her calculated footsteps in the distance, her blaster eviscerating anything in her path. SA-X is first introduced in a cutscene where Samus is in no real danger. Her next few appearances happen through gameplay, but Samus will be safe so long as you stay put. Each encounter introduces a new layer of danger and interconnectivity until SA-X eventually chases you through a series of different rooms — only letting up when she physically loses sight of Samus.

More than a stalker, SA-X is you but better. It can be jarring to see what you should walk around, but the situation is made so much worse once you realize SA-X has all of Samus’ best abilities. She will freeze you with the Ice Beam just to follow up with Super Missiles or Screw Attack right into Samus if you slow down. SA-X is a vicious predator, but Samus is no slouch herself. Fusion’s control scheme is far less physics-based than Super, lacking as much emphasis on momentum. This leads to less platforming depth, but Fusion makes up for it with intuitive controls that elevate the level design.

Samus’ movement is snappy and responsive, which plays well with how quickly Fusion loads areas. Her center of gravity is no longer as floaty as it was in Super, leading to tighter platforming in some cases. Rather than merely simplifying what Samus can do, she can now climb and cling to certain alcoves. Ladders and monkey bars are a staple of BSL’s level design, showing how scientists practically got around the six sectors. Monkey bars are often high above environmental hazards and enemies to carefully move across while avoiding damage. Ladders similarly play a role in a few puzzles where you need to position Samus properly so she can destroy adjacent walls.

Owing to Fusion’s restrictive game design, Wall and Bomb Jumping are nowhere near as useful as they were in Super. Wall Jumping forces Samus to jump towards whichever direction she was pushing against. Infinitely jumping up a single wall is now impossible, but this hardly matters since the level design doesn’t account for it to begin with. Fusion’s Bomb Jumping also disallows the rhythmic chaining possible in Super. You can get some height, but nowhere near enough to pull off creative Morph Ball platforming. If nothing else, Wall Jumping is a useful way to dodge bosses when their arenas allow it.

Fusion’s platforming is different enough where it might not fully satisfy Super Metroid diehards, but combat is improved on every front. Directional aiming returns with one key tweak to make it smoother. You can still aim manually, but holding L locks Samus into a directional aim that you can adjust by pressing Up or Down on the D-Pad. This makes aiming diagonally while moving much easier. In a notable change, Samus’ Beams finally all stack. You no longer need to pick and choose which to equip since the Charge, Wide, Plasma, and Wave Beams complement each other. Unlocking each Beam in a set order keeps combat balanced while raising Samus’ strength in increments.

The GBA’s limited button layout actually ends up being a blessing in disguise for Fusion. Super had Samus select her weapons by rotating through a five-item menu in real-time. This gets the job done but obviously leaves a lot to be desired. Without a Y button (and Select better used elsewhere), you now equip Missiles and Power Bombs with the hold of a button. Holding R while standing equips Missiles while equipping Power Bombs in your Morph Ball form. To avoid menu management, on the whole, Missiles upgrade linearly, turning into Super Missiles, Ice Missiles, and finally Diffusion Missiles.

Super Missiles buff Samus’ damage, while Ice Missiles offer an interesting replacement to the Ice Beam. Ice Missiles turn the Ice Beam into a strategic tool in theory since ammo needs to freeze enemies. Fusion makes it difficult to actually run out of missile ammo thanks to an abundance of recharge stations, but Ice Missiles are still a nice change of pace. Diffusion Missiles are essentially the Charge Beam of missiles. Holding down R long enough charges up a blast of cold air that freezes every enemy on-screen.

The entire upgrade process has been heavily revamped from previous Metroid games. For one, upgrades are actually explained in-game when you pick them up. Where you would once hunt down upgrades organically, all of Samus’ major improvements are telegraphed as part of the story. More often than not, Samus will be exploring a new sector specifically to unlock an ability. A good chunk of upgrades are now obtained from Data Rooms, directly downloaded from the Federation themselves. This usually amounts to different Beams, Missiles, and Bombs. The rest of the upgrades are unlocked by killing bosses.

BSL’s X infestation all reproduced from the parasite that infected Samus’ Power Suit, so certain bosses have access to her abilities (Serris’ replica has the Speed Booster, Nightmare has the Gravity Suit). Fusion turning Samus’ best abilities into boss fights is a clever way of making you reacquire skills like the Space Jump and Screw Attack. The only downside is that this leaves Energy Tanks, Missiles, and Power Bombs as the sole upgrades to find as side content. Fusion compromises by making even early upgrades challenging to grab in their own right.

Turning the Hi-Jump and Spring Ball into a single upgrade (the Jumpball) might seem like streamlining, but it actually raises the skill floor. Combining two platforming abilities into one early ability, the Jumpball lets sophisticated platforming be an inherent part of Fusion’s level design. This can be seen best in the Speed Booster and Shinespark. To save on buttons, Samus dashes on her own. Once you unlock the Speed Booster, the ability triggers automatically if you run long enough.

Pressing down on the D-Pad after breaking the sound barrier (visualized by Samus’ sprite glowing) lets you break into a Shinespark, a technique that launches Samus into whatever direction you’re directing her. Shinesparking no longer drains health and is easier to pull off in terms of timing. You can store your Shinespark to use for later or chain it — a skill required to 100%ing the game. By Shinesparking into a slope, Samus will actually stop in her path, allowing you to recharge your Shinespark, reposition, and then launch off further than you would have otherwise.

Enemies deal a considerable amount of damage compared to earlier titles, which makes sense considering Samus is missing huge chunks of armor. Likewise, her newfound Metroid DNA makes her vulnerable to ice, and the X Parasite’s infection would naturally take some physical toll on her. Samus is fighting for her life in weak, unfamiliar gear. Health gets drained fast, and careless players will be swarmed by respawning enemies. It’s not unusual to lose dozens of HP from just contact damage. Several rooms throw enemies at you fast enough where quick reflexes are necessary not to take any damage.

Fusion’s combat is at its best during boss battles. BSL is swarming with bosses, and each one puts up a hell of a fight. Since Samus’ actions are more responsive, bosses have more aggressive attack patterns. Serris rushes the screen back and forth with the Speed Booster, twisting around the arena and requiring you to time your shots carefully. Nightmare rushes right towards Samus’ body, forcing you to bait it while dealing damage whenever safe. SA-X counters your attacks with specific techniques, Screw Attacking if you Screw Attack, and spamming attacks virtually non-stop. Adding tension is the fact that bosses morph back into their parasitic forms once “defeated,” prolonging fights and putting the X Parasite’s threat into perspective.

Bosses are a visual spectacle, but Metroid Fusion, in general, is one of the best looking, sounding, and feeling games on the Game Boy Advance. Releasing so early (a single year) into the GBA’s life cycle shows the potential of the handheld in full force. Fusion is to the Game Boy Advance what Return of Samus was for the original Game Boy: an atmospheric tour de force that plays to handheld gaming’s strengths. BSL’s carefully crafted level design immerses you into a horrifying space station that cuts away the threads of familiarity for a fresh take on Metroid.

Minako Hamano returns to compose the soundtrack, this time accompanied by Akira Fujiwara. Fusion’s score pivots from Hamano’s work with Kenji Yamamoto on Super Metroid, sticking to a creepy, isolated tone that clashes with Super’s naturally atmospheric sound. Voice acting for in-game alarms makes the setting more immersive and lends the story a cinematic feel. Unique settings courtesy of naturalistic biomes placed in a mechanical facility lead to bizarre backdrops that touch on a new type of “alien” for Metroid. Fusion’s sprite work and art direction are so strong that the game looks better than Super in some respects.

Despite a more traditional narrative, there is still a focus on subtle, environmental storytelling. Every sector except ARC resembling an area from one of the first three games is a sign that the Galactic Federation is using BSL to study Samus’ adventures. You run into Serris’ skeleton after an entire sector of build-up only to be blindsided by its infected mimic (something you might have seen coming, given how X Parasites behave). There’s even a chilling Ridley reveal out of nowhere that sets up the battle against Neo Ridley.

Less is more when it comes to Fusion’s script. Adam offers context every time Samus enters a new Navigation Room, but these “cutscenes” often take less than a minute to read and add to the overall ambiance. It only makes sense that an artificial intelligence given to Samus by a military organization would force her to do everything by the books. This comes full circle when Adam goes rogue for Samus at the end of the story and defies his Federation allegiance to help her destroy BSL.

Samus’ relationship with Adam is a massive narrative strength, if only because it offers actual context into her feelings on the Galactic Federation. The original trilogy posits the Galactic Federation as an ostensibly heroic organization and Samus’ main benefactor. They keep the galaxy at peace, but now they’re continuing Mother Brain’s legacy by finishing her work on Metroid cloning. Fusion characterizes Samus as a stoic bounty hunter who only works with the Federation reluctantly. She mentions how much she dislikes taking orders in one of her first monologues and chooses not to engage with Adam for most of the plot.

Keeping the majority of Samus’ dialogue relegated to an inner monologue fleshes her out, but not in an overbearing way that takes away from the gameplay or weakens her character. It helps that Samus is rebellious to her core. Fusion ends with her turning on the Federation she has worked for throughout the series, destroying a station full of valuable (but extremely dangerous) research. Samus ends the story pondering how intensely her status quo has changed, potentially making an enemy out of the Galactic Federation, but that’s a fitting conclusion for a game all about pivoting from Metroid’s established norms.

While cut from the US release (for some inexplicable reason), Fusion takes this added focus on Samus to its logical conclusion by showing audiences her backstory for the first time. Instead of seeing Samus in her underwear, ending images highlight different chapters in her life: Ridley killing her parents, Samus being adopted by the Chozo, and training to become a bounty hunter. Offering insight into Samus’ past is a great way of encouraging repeat playthroughs, but Fusion’s replay value is rooted in the sheer strength of its game design. 100% speed runs recontextualize BSL into a massive puzzle where you need to figure out when to nab each upgrade, offering you little room for error.

For fans who do not care for speedrunning, Fusion is the first Metroid to feature an actual post-game. Booting up a completed file lets you finish exploring BSL with few restrictions. You need to make use of inter-sector shortcuts because of all the damage SA-X has done, but this just keeps navigation engaging while finally pushing for exploration. Your map even keeps a tracker of how many Missiles, Power Bombs, and Energy Tanks you found in each sector, preventing aimless wandering. Exploration never gets as freeform as Super, but making the post-game open-ended is a fine compromise that lets the main playthrough stay linear.

Fusion robs you of Metroid’s most familiar aspects, but not without reason. Level design makes the most out of linearity, standing out as a genuine counterpart to Super. Even the best Nintendo franchises have a habit of playing things safe to the point of coming off derivative, but not Metroid. A straight port of Super Metroid likely could have been pulled off on the Game Boy Advance, but it would have been a disservice to SM, the GBA, and Metroid’s penchant for experimentation in every sense. Just like Super Metroid before it, Metroid Fusion is a 16-bit masterpiece.

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks agoDon’t Watch These 5 Fantasy Anime… Unless You Want to Be Obsessed

-

Culture3 weeks ago

Culture3 weeks agoMultiplayer Online Gaming Communities Connect Players Across International Borders

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks ago“Even if it’s used a little, it’s fine”: Demon Slayer Star Shrugs Off AI Threat

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoBest Cross-Platform Games for PC, PS5, Xbox, and Switch

-

Game Reviews3 weeks ago

Game Reviews3 weeks agoHow Overcooked! 2 Made Ruining Friendships Fun

-

Guides4 weeks ago

Guides4 weeks agoMaking Gold in WoW: Smart, Steady, and Enjoyable

-

Game Reviews3 weeks ago

Game Reviews3 weeks agoHow Persona 5 Royal Critiques the Cult of Success

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks ago8 Video Games That Gradually Get Harder

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoThe End Is Near! Demon Slayer’s Final Arc Trailer Hints at a Battle of Legends

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks agoDon’t Miss This: Tokyo Revengers’ ‘Three Titans’ Arc Is What Fans Have Waited For!

-

Guides2 weeks ago

Guides2 weeks agoHow to buy games on Steam without a credit card

-

Game Reviews1 week ago

Game Reviews1 week agoFinal Fantasy VII Rebirth Review: A Worthy Successor?

Winwin

July 23, 2021 at 4:34 pm

All I want is a Metroid movie with Brie Larson. That is all I want. YOLO

Sean colvin

July 24, 2021 at 2:42 pm

meh. zero mission was better and harder. Fusion was paint by numbers.

Chango_wero

July 27, 2021 at 7:21 pm

Excellent piece of writing brother.

Fusion is indeed a great game any metroid fan should play. I’m really excited to see where metroid dread will take us.