Features

A Look at Morality in Video Games

More than just Good vs. Evil

Morality is No Gimmick

Games are the perfect means to test a person’s morality. Give players the power and privilege to behave and act as they please and you should see a range of responses to every situation, small insights into what a person is really like. It’s strange then, that so many players tend towards the side of good”, or the “morally just” option.

Is this because, deep down, all people are morally just? Whether by human instinct to look out for each other, or due to the deeply ingrained rules of the society they abide by? Possibly. Is it because people, no matter how selfishly or questionably they would like to act, are naturally inclined to want to be seen as “good” by others? Even if those others are entirely fictional NPCs, or faceless Karma systems? Again, quite possibly. But a large part of it may also be down to the way games present morality. More specifically, the way they handle moral choices.

The problem with moral choices is the fact that they are so often distinctly separate from the rest of the gameplay. A main character who has no qualms about killing dozens upon dozens of faceless goons (each of whom probably has a family somewhere and is only doing what they were paid to do), but tears their hair out when faced with the choice of whether or not to spare the final boss, simply because it’s part of an emotion cutscene, doesn’t quite add up. This kind of ludonarrative dissonance has been discussed to no end, but it’s an interesting by-product of the evolution of games as a medium, nonetheless.

It’s All Down to Choice

Choices in video games stem from their tabletop routes. In these dice-rolling, dragon-slaying RPGs of old, players are recommended to give their character an alignment – lawful good, chaotic neutral, neutral evil, etc. – which would inform the player’s actions and choices going forward. Essentially, giving each player a little nudge in a new direction so that their high elf warlock doesn’t default to their own real-life personality. And anyone who has played Dungeons and Dragons can attest that, while simplistic, it works. And it works best when you have a good Dungeon Master, who not only puts their players into mentally challenging or morally questionable situations, but accepts and adapts to any solution their players put forward.

This is where video games start to struggle. They may give the player the choice of how to act, to decide what kind of person they want their main character to be, but they are limited by their own medium. Tabletop games take place primarily in their players’ imaginations, where almost anything is possible, and if the players come up with a solution that the Dungeon Master hadn’t thought of, or decide to be complete jerks and ruin the lives of those they are supposed to save, then that’s okay – the game can adapt. Video games, on the other hand, need to be coded. Characters need to be animated, voice lines need to be written and recorded, and scenarios need to be built, tested, and finalised. It is simply impossible to do whatever you want in a video game – developers don’t have the time, money, energy, or even imagination to account for that.

Because of this – because of all the time and effort that goes into making even a straightforward gaming narrative, let alone one which choices – many games that play with morality tend to offer a simple binary: Good or Evil. While there’s nothing inherently wrong with this, and it does allow players to play the game their own way, it is rather reductive.

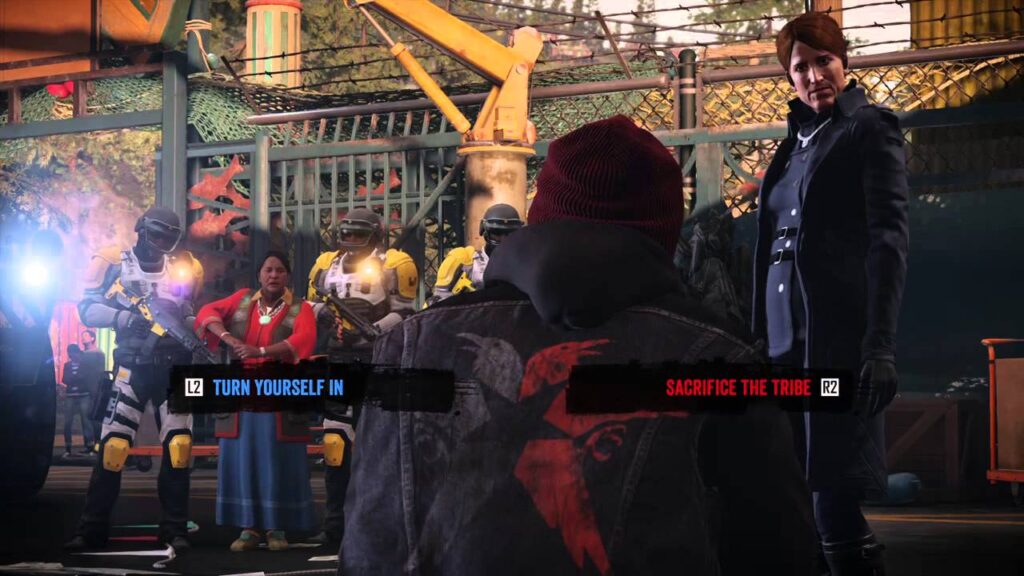

Morality is a complex subject, filled with grey areas and blurred lines, reducing it to a simple “Good” or “Bad” choice kind of defeats the point of including it. Especially when skills, rewards, and endings are tied to doubling down on one specific path. Think about the Karma system in the Infamous games. Despite promising complex dilemmas, the choices on offer are decidedly one-note, with it made very clear to the player which choice is the “good” (blue) choice and which is the “bad” (red) – Do you give the food to the starving civilians or keep it for yourself and let them die? Here the choice is definitely a matter of playstyle over morality, and considering the only way to unlock the very best skills is to fully commit to either being a hero or a villain, the illusion of choice very quickly shatters.

But it’s worse when a game clearly favours one side over the other. Bioshock attempted to “shock” its players with the option to “Harvest” (or kill) its Little Sisters in order to immediately gain a large boost of Adam – the material needed to gain new Plasmids and upgrade old ones – or “Save” them for a lesser reward. What starts out as a truly terrible question – would you sacrifice a child to make your own struggles easier? – quickly becomes redundant when players realise they will actually get more Adam in the long run for saving the little girls, completely removing any moral quandary they may have originally been struggling with.

The Hero or the Jerk

The Mass Effect series has its Paragon and Renegade options, a mechanic that allows for some exceedingly generous or truly spiteful interactions, and has clear roots in Dungeons and Dragons’ alignment system. It’s great for roleplaying the galaxy’s greatest hero/jerk, but does nothing to address the grey area in between. The problem is, to achieve the best endings in the game and get the most out of your experience, players will need to fully commit to just one of these paths from the very start of the game.

My first experience with the Mass Effect universe was with playing Mass Effect 2 when it finally came to the PS3. My Commander Shepherd didn’t fit in with the straightlaced Paragon or hard-edged Renegade, but landed somewhere in the middle. He was the kind of man you could rely on to get you out of a tough situation or have your back when you were feeling low, but was not averse to throwing a man out a ten-story window if they looked at him funny. Because of this, my Paragon/Renegade points were fairly balanced and I was locked out of certain dialogue choices later down the line. As such I couldn’t calm both Jack and Miranda down when a heated argument broke out on my ship. Funnily enough, not having high enough Paragon or Renegade points to talk them both down presented me with my first truly difficult choice: who should I side with?

At this point in the game, I was invested in both of them, both were valued members of my crew, both would remember my choice, and whichever one I didn’t pick would lose my trust forever. I ended up picking Miranda, and as a result, Jack died during the Suicide Mission, locking off her story arc in the third game. At first, I felt conned, that I was being punished for playing the game my own way instead of going down one of the paths presented to me, but then the choice, and its consequence, grew on me. It changed my experience of the game – I had to live with what I’d done – and it’s a choice I wish every player had to make.

Do the Ends Justify the Means?

Consequences are what make or break true moral choices. If there is no real consequence to your actions, does it really matter whether you were nice or not? The Fallout games and Red Dead Redemption 2 have similar systems that assign morality points based solely on the player’s immediate actions, never mind what might come of them.

In Fallout 3, for example, whenever the player engages in stealing, lockpicking, or killing of important or innocent characters, they lose Karma. This is understandable, of course, but what if they were breaking into one character’s house to steal documents that prove another character’s innocence? According to the game, that doesn’t matter. Lockpicking is lockpicking, stealing is stealing, lose Karma. The player may gain positive Karma for handing over that evidence later, but in each case, it’s the action, not the result, that gets the points. There is no “the end justifies the means” in Fallout’s wasteland.

And with Red Dead Redemption 2’s Honor system, it’s very easy to play the hero in the main storyline while still spending your free time murdering passers-by and hogtying strangers like a psychopath. Just as long as you keep contributing to your camp and caring for your horse to top up your “good” Honor, you can be as despicable as you please. There are no long-term repercussions to your actions. (Not that it isn’t fun to let loose and go on a rampage every now and then.)

There Are Always Consequences

Actions matter, but so do their consequences. And no game shows the power of unintended consequences better than The Witcher 3. In the war-torn country of Velen, there is no right and wrong, there are only people, doing their best to survive. Geralt’s journey through this ravaged land shows him all sides of humanity, from the corrupt to the desperate, the manipulative to the genuine, but worst of all, it asks the player to decide who is right, and then shows them exactly what their choices wrought.

Like the curse of the monkey’s paw, even if the player tries to do the “right” thing, bends over backwards to find a solution that benefits everyone, or helps the needy and punishes those who abuse their power, something unforeseen will always undermine them. Track down a drunk arsonist and hand him over to the authorities expecting he’ll just receive a slap on the wrist? Arson is a capital offense in Nilfgaard, and now you have to stand by and watch as a poor man is led away to the gallows. Want to help a desolated village by ridding it of a malevolent spirit? That spirit was the only thing keeping a trio of witches from devouring an innocent group of orphans. No matter how the player chooses to act, someone, somewhere, always loses.

And to make matters worse, the game never presents these choices as “good” or “bad”, but “bad” and “bad”, and asks the player to decide which is the better of the two. So much for Geralt’s famous line in The Last Wish book:

“Evil is evil. Lesser, greater, middling… Makes no difference. The degree is arbitrary. The definition’s blurred. If I’m to choose between one evil and another… I’d rather not choose at all.”

Sorry, Geralt, old buddy, if you ever want to finish the game and save Ciri, you’re going to have to pick one, and live with the consequences.

Not a Single Choice, but a Way of Life

But games become much more interesting when they bake their morality into their gameplay – when every choice a player makes, no matter how small it may seem, carries with it the weight of severe consequence. Games like This War of Mine, in which the player is put in the shoes of the desperate and the starving and is told to do what they can to survive. Where the actions they know to be morally right may result in little or no resources as a reward, and those actions they know to be morally reprehensible grant an abundance, at the cost of their character’s humanity.

Or Papers, Please, a grim dystopian nightmare in which players must conform to increasingly strict and bizarre rules in order to do their job as a border control officer and earn enough money to feed their family. The problem is, there is never enough money to feed everyone, especially when the weather turns bad and heating bills rise, or rent goes up without warning. And then what is the player to do when a man comes through with all of the correct documents in order, but his wife following him does not? Do they let her through and risk having their pay docked? Or turn her away to guarantee a bigger pay packet at the end of the day, splitting apart the loving couple forever?

It’s in games like these that a player’s true nature can be observed – are they happy to let others suffer and die to get what they want or feel they need, or are they willing to make sacrifices, to give everything to a stranger in need, even if the only reward is satisfaction and a small smile of hope? Games, unlike other, more passive media, are uniquely suited to challenging a player’s morality, so it’s about time developers start to take it a little more seriously.

-

Culture4 weeks ago

Culture4 weeks agoMultiplayer Online Gaming Communities Connect Players Across International Borders

-

Features4 weeks ago

Features4 weeks ago“Even if it’s used a little, it’s fine”: Demon Slayer Star Shrugs Off AI Threat

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks agoBest Cross-Platform Games for PC, PS5, Xbox, and Switch

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks agoThe End Is Near! Demon Slayer’s Final Arc Trailer Hints at a Battle of Legends

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoPopular Webtoon Wind Breaker Accused of Plagiarism, Fans Can’t Believe It!

-

Features4 weeks ago

Features4 weeks ago8 Video Games That Gradually Get Harder

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks agoDon’t Miss This: Tokyo Revengers’ ‘Three Titans’ Arc Is What Fans Have Waited For!

-

Game Reviews2 weeks ago

Game Reviews2 weeks agoFinal Fantasy VII Rebirth Review: A Worthy Successor?

-

Guides3 weeks ago

Guides3 weeks agoHow to buy games on Steam without a credit card

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoSleep Meditation Music: The Key to Unwinding

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoThe 9 easiest games of all time

-

Technology2 weeks ago

Technology2 weeks ago2025’s Best Gaming Laptops Under $1000 for Smooth Gameplay