Features

Like Father Like Son: Depictions of Masculinity in God of War

Whether you love them or hate them, the God of War games are some of the most important titles in PlayStation history. Since 2005 Sony’s Santa Monica Studio has been responsible for chronicling the vengeance-fueled adventures of Kratos and for creating a franchise that defined the meaning of hack and slash gaming for the previous two console generations. Ever since the PS4 launched in 2013 the absence of a new God of War game has been somewhat perplexing, but if popular and critical reactions praising this year’s entry to the high hall of Odin are accurate (spoiler alert: they are) then it’s all too clear that the five-year hiatus was not in vain.

As a long-time fan of the PlayStation brand, I’ll willingly admit that earlier incarnations of Kratos failed to capture my imagination. Objectively I knew that the previous three main entries in the series were the stuff that AAA dreams are made of; there’s no way that they could have garnered such huge sales and an avid fan base if they weren’t. However, subjectively, I never found the character or his quest to butcher his way through the entire Greek pantheon to be all that compelling. Far from being a poster boy for the brand, Kratos was, for me, just another manifestation of everything about masculinity my generation was raised to find abhorrent.

Bizarre as it might sound, Kratos’ unrelenting fury and obsessive-compulsive thirst for vengeance against the gods that betrayed him, robbed him of his family, and in the end stripped away even his humanity struck me as a little bland. Clearly, the character and the stories told about him never wanted for motivation or pathos, but even when the stakes were raised as high as the summit of Olympus itself I wanted more from my protagonist than slavish devotion to blind rage, and I still do.

In what is both a continuation and a simultaneous soft reboot of the franchise, God of War offers up an older, wiser, less indiscriminately murderous Kratos; one whose blood lust is tempered by a level of rationality that until now he was seemingly incapable of. The result is a profoundly moving narrative-driven just as much by character interaction and development as it is by spectacular combat and action set pieces. It’s a story that begins with the humble objective of father and son on a journey to scatter the ashes of Faye, their recently deceased wife, and mother respectively, and ends with the first stirrings of Ragnarok – the fall of the Norse gods and the end of the world.

So what is it that prompted this paradigm shift? Why has Kratos gone from being the embodiment of unrepentant indulgence in the very worst human characteristics to being someone who isn’t just relatable but also even likeable?

In the eight years since God of War 3 was released gamers familiar with the series, the developers behind it, and Kratos himself have aged. Simply put none of us are as young as we once were and consequently, our perspectives on life have evolved beyond the point where the immediate gratification offered by tearing monsters the size of mountains in half is no longer the be-all and end-all of our expectations. Don’t get me wrong, that’s something that any aspiring demigod would want to tick off their bucket list, but as gamers and the industry have matured over the years it’s only natural that we should aspire to greater things.

Unabashed power fantasies have their place in all forms of entertainment, not because they speak to some default chauvinistic philosophy rooted deep in the male psyche but rather because they allow us to take a step outside of our own lived experience. In doing so we’re able to imagine solutions to problems and resolutions for situations that we otherwise might not have been capable of imagining ourselves. To a greater or lesser extent players are able to accomplish this by projecting themselves into the position of the protagonist, even if that individual is not someone we would ever aspire to be.

Most male gaming protagonists are either portrayed as Kratos used to be, perpetually dour and violent beyond reason, or as inexplicably competent buffoons like Nathan Drake. Male protagonists are often considered to be universally positive representations of heroism and power, but in truth, a lot of these characters are fundamentally damaged in some way and are far from being upstanding examples of masculinity. The diametric opposition between the two extremes and the implicitly exclusionary divisions it engenders is a point that feminist game critics have quite rightly made in the past. That almost every headlining character has been some variation on the theme of miscellaneous Caucasian males does reflect an imbalance in the industry. An imbalance that is gradually being redressed by titles like Horizon Zero Dawn and the Tomb Raider series as female protagonists finally grab some measure of the spotlight. The story of 2018’s God of War however speaks to a uniquely male experience: fatherhood.

Whether or not we want to admit it, most men have at least some measure of desire to be fathers. God of War being grounded in a re-imagining of the nine realms of Norse mythology where most problems can either be solved by swinging an axe at them a few times or using a convenient magic trinket, doesn’t mean that it can’t be used as a structural metaphor for the relationship between father and son. If we’re lucky enough to know our fathers (close to 4 million kids in Britain alone don’t have that apparent luxury) then we also know that getting along with them isn’t always easy.

From our earliest childhood and through our formative years, fathers are ideally the first example boys have of what they should aspire to be. From them, we learn the basics of what it is to be male in a world that often demands we be all things simultaneously. While in some instances our fathers are not always set the best example they ideally try to guide us to a point where we can be relatively happy and productive men. In reality, this takes the form of shared experiences, awkward conversations, and even verbal or physical confrontation. In God of War, this bonding process is mirrored by the mechanical aspects of its gameplay and the structural elements of its narrative.

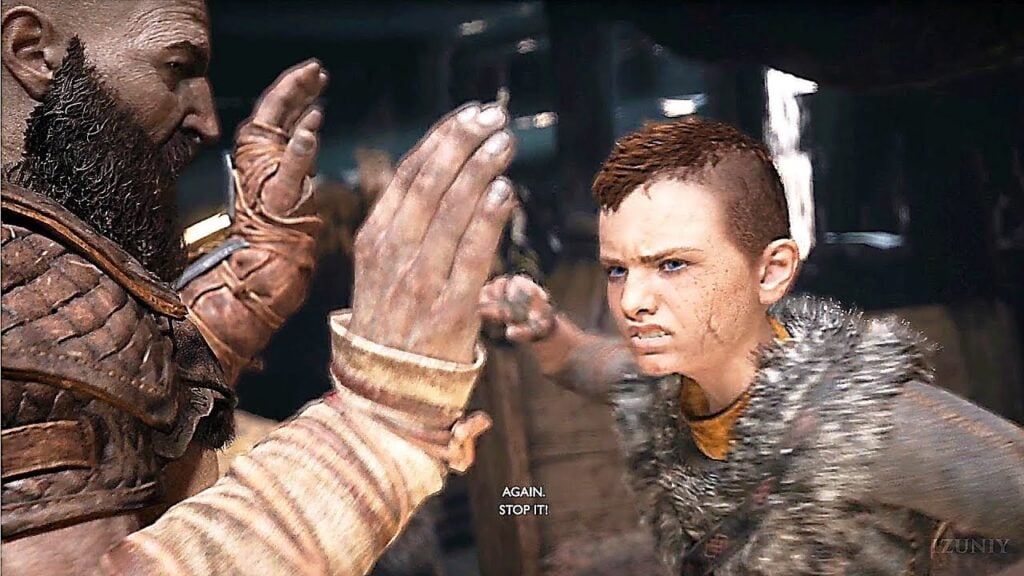

As players progress through the story they participate in innumerable combat scenarios all of which garner experience points and loot that can be used to unlock new abilities and perks. Over time they change the ways that Kratos and Atreus work together to defeat increasingly powerful and varied enemies. At first, Kratos continually admonishes Atreus, urging him to focus and concentrate without any thought for how he feels. In later stages of the game, these harsh words mellow and soften until the point where praise and gratitude begin to take their place. At certain pivotal plot points, the game world expands revealing previously submerged areas ripe with new treasures, encounters, and quests. At the same time, the relationship between Atreus and Kratos also expands and evolves as they are required to overcome the new scenarios and encounters, and take advantage of new opportunities provided by the ever-changing world around them.

Throughout the game Kratos invariably (with a few exceptions) refers to Atreus as “boy”. Whether Kratos is calling for assistance in combat or demanding translation of a runic inscription it would be entirely possible to see this constant affirmation of Atreus’ status as a way of denigrating the child; of inherently emphasizing his deficiencies whilst highlighting Kratos’ comparative superiority. Seen in this light you’d be forgiven for thinking that he hasn’t changed at all and that underneath he still seethes with the demigod equivalent of the same fratboy-friendly roid rage that was a core aspect of the original character.

But far from being a deliberate assertion of Kratos’ dominance over Atreus, this apparent outright refusal to call his son by his own name is both a teaching mechanism and a coping strategy. By drawing attention to Atreus’ weakness and inexperience, Kratos is in fact encouraging his son to constantly seek out ways to improve and to make sure that he never makes the false assumption that he is either invincible, infallible, or inherently better than other beings. It also helps him process the fact that his son is rapidly maturing and will soon have no need for constant guidance. As much as getting his son to that point is part of Kratos’ duty as a father, it is a bittersweet task, one that sees him constantly reference Atreus’ current status to protect himself from the knowledge that his child will not be a boy forever. Yet even as he seeks to preserve his child’s innocence, to protect him from the world and knowledge of his true self, Kratos can’t see the harm he is inflicting upon him.

When Atreus falls ill as a result of the conflict between his divine heritage and his perception of his own mortality, Kratos finds himself alone again. With the boy left in the care of Freya he is forced to retrieve his former weapons, the Blades of Chaos, and his past literally returns to haunt him as visions of Athena reawaken the Ghost of Sparta. This narrative and gameplay shift is the perfect metaphor for what happens when a man finds himself without genuine purpose. He turns in on himself and is able to focus on nothing but the demons that drive him; you need only look to statistics regarding unemployment and suicide for example for proof of that. Atreus is Kratos’ last remaining positive motivation and having become accustomed to the role that the boy plays both in and out of combat the player feels his absence just as much as Kratos does. The tempo of the game changes in response as some puzzles and encounters become more complicated or outright unsolvable at that time. In this way, the game makes a conscious effort to show how dependent on each other they are and how fundamentally essential the connection between father and son is.

After Atreus learns of his godhood and confesses that he believes that he is not the son that Kratos wanted, he is giving voice to a universal male fear: the fear of being a disappointment to themselves, the world, and to their fathers. As the two discuss what it means to be a god, Kratos muses that it is a curse that begets nothing but anguish and tragedy whilst Atreus asks cautiously optimistic questions about the extent of his abilities. Neither of them knows exactly what Atreus will grow up to be or what he is capable of. Just like fathers and sons the world over those are things they will discover together as they enter into each new phase of their relationship.

This is demonstrated by the way in which Kratos reacts to his son’s tentative acceptance of his godhood. Kratos’ job, like that of any father, is to make sure that his son is able to learn and grow at his own pace and to fully embrace the things that make him unique. Atreus may not be as physically gifted as his father, but Kratos comes to rely on Atreus’ unique faculty with languages and rune magic to overcome all manner of obstacles that stand between them and the completion of their quest. This draws attention to the fact that men are just as diverse and multi-faceted as any other gender, be it biologically determined or self-identified. Things don’t always go according to plan, however. Atreus begins to grow callous towards beings who aren’t gods and is disdainful of what he views as little people and their little problems. He takes his power for granted and ignores all the guidance that Kratos has been offering. For a while, he stops being the Atreus we’ve come to know and he begins to take on traits previously exhibited by Baldur.

Freya and Odin’s wayward son is wrathful, arrogant, reckless, and vengeful. He is all that Kratos was and all that he fears Atreus could become. Acting as the central antagonist of the story, Baldur constantly hunts Kratos and Atreus for the knowledge they possess regarding access to the lost realm of Jotunheim, home of the giants. At each encounter he is unjustifiably boastful and aggressive, throwing all caution to the wind as he attempts to carry out the Allfather’s will and accomplish his mission. In short, he is the embodiment of what modern parlance refers to as “toxic masculinity.”

Over time his appearances begin to take their toll on Atreus, who sees such obvious use of power as an inherent part of being a god. Yet Baldur’s furious facade is just that, a front, one he uses to mask the desperation and sorrow he feels after being been blessed, or cursed, by his mother with a Vanir spell that grants him absolute invulnerability and immunity to all feeling. He may not be able to feel pain but for an entire century he has been robbed of all the things that make life worth living; the pleasures of food, drink, and sex is all distant memories for him. By the time that the enchantment is broken by a splinter of mistletoe, the darkness in his heart has consumed him, and even at the point of death, he wants nothing more than to kill his mother for the burden she placed upon him. It is only as Mimir’s grandfatherly advice reveals the sacrifices made by the Aesir god, Tyr, in his endeavors to protect the race of giants from Odin’s wrath that Atreus comes to understand that Baldur’s path only leads to ruin and he learns the value of tolerance, co-operation, and respect.

God of War is a phenomenal game, there can be no doubt of that. The sheer level of passion that has gone into every aspect of it has resulted in a title that resoundingly re-confirms Sony Santa Monica’s place as one of the best development studios operating in the industry as it stands today. It more than deserves to take its place alongside this generation’s greatest games. It also more than capably illustrates that linear single-player games are far from irrelevant to the modern industry, and helps put paid to the assumption that stand-alone games are a thing of the past.

Yet there’s another reason why it is such an important work. In an era when external observers can seemingly do little more than condemn men simply for having the temerity to be born male, and criticize every aspect of masculinity no matter how trivial, this game attempts to balance the scales. Some might say that the changes made to Kratos and the core game features of the series is an attempt to pander to a social justice warrior-mandated, “liberal” media approved agenda that simply refuses to let men, even fictional ones, exist on their own terms. Such criticism, although founded in a certain kind of logic, overlooks the fact that the game does the exact opposite.

Allowing Kratos to express himself with something other than snarls of fury and enabling him to interact with the world without immediately resorting to savage violence gives him more freedom to pursue his goals, not less. It gives him greater, not less, depth as a character because he can approach any given situation with something other than murderous intent. Instead of being needlessly domineering and oppressive, Kratos’ stern instruction and direct approach to education allow Atreus to find his feet even if he does stumble along the way. By highlighting the value of temperance over rage, perseverance over despair, and competence rather than dominance, God of War tries to show that although men can be monsters we can be gods, or at least decent human beings, as well.

-

Features4 weeks ago

Features4 weeks agoThis Upcoming Romance Anime Might Just Break the Internet; Trailer Just Dropped!

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks agoDon’t Watch These 5 Fantasy Anime… Unless You Want to Be Obsessed

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks ago“Even if it’s used a little, it’s fine”: Demon Slayer Star Shrugs Off AI Threat

-

Culture2 weeks ago

Culture2 weeks agoMultiplayer Online Gaming Communities Connect Players Across International Borders

-

Game Reviews3 weeks ago

Game Reviews3 weeks agoHow Overcooked! 2 Made Ruining Friendships Fun

-

Features5 days ago

Features5 days agoBest Cross-Platform Games for PC, PS5, Xbox, and Switch

-

Guides4 weeks ago

Guides4 weeks agoMaking Gold in WoW: Smart, Steady, and Enjoyable

-

Game Reviews3 weeks ago

Game Reviews3 weeks agoHow Persona 5 Royal Critiques the Cult of Success

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks ago8 Video Games That Gradually Get Harder

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoDon’t Miss This: Tokyo Revengers’ ‘Three Titans’ Arc Is What Fans Have Waited For!

-

Game Reviews5 days ago

Game Reviews5 days agoFinal Fantasy VII Rebirth Review: A Worthy Successor?

-

Guides1 week ago

Guides1 week agoHow to buy games on Steam without a credit card