Game Reviews

Anemoiapolis – Liminality and Horrors in the Space Between

Anemoiapolis captures the unique terror of liminality. The unsettling feeling of the spaces between, things that are almost but not quite familiar.

Anemoiapolis Review

Developer: Andrew Quist | Publisher: Andrew Quist | Genre: Horror

Platforms: PC | Reviewed on: PC

Liminality; it’s a term used to describe the psychological process of transitioning across boundaries and borders. Imagine this liminal space as a corridor that takes you from one room of a house to another, a quite literal space between, defined by the transition of one place to another. But what if that corridor only leads to more corridor? Without the destination or the starting point everything begins to feel off, and there’s a feeling of isolation and deep-seated knowledge that everything is somehow wrong. That unique terror, one that only builds and builds as the space stretches on, is what Anemoiapolis has captured.

Anemoiapolis sees the player arriving at a familiar looking landscape with the intention of fixing a generator. The sun is out, everything is bright, and you are all alone. In wandering about, you fall deep into a surreal labyrinth. Still alone, you must take the only course of action you can: exploring the uncomfortable locale and trying your best to understand the unfathomable.

Everything looks almost familiar, and it’s easy to get in your own head about whether you’ve taken a wrong turn or if the landscape has changed in some almost imperceptible way since you last were there. The aesthetic is intoxicating, and the nostalgic areas capitalize on kenopsia (the eerie atmosphere of a place that is usually bustling with people but now abandoned).

Liminal Spaces

In recent times we’ve seen a rise in the popularity of liminality, with Skinamarink and especially The Backrooms taking off due in no small part to Kane Pixels’ fantastic short film. A whole slew of games have been born from that side of things, but there’s a bit of a difference here. Whilst the majority of the Backrooms’ games (there are exceptions) lean on the idea of some spooky scary creatures hiding in the labyrinth, Anemoiapolis focuses in on the calm yet disquieting feeling of those spaces between.

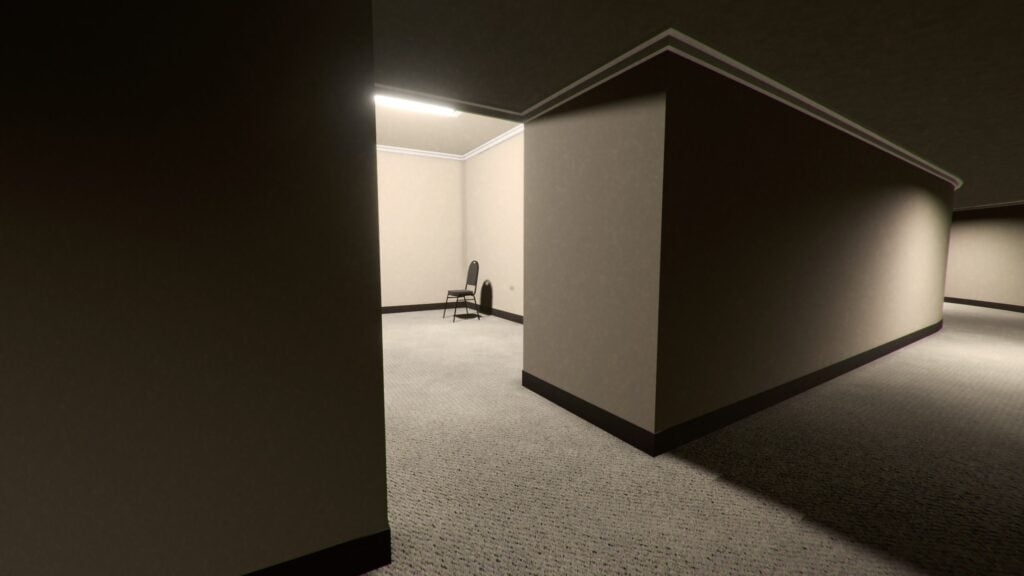

That’s not to say there’s no looming sense of danger. Peeking around corners and seeing corridors stretch and twist, darkness radiating, and things that seem to be signs of habitation yet without any occupants is unsettling. The game does a great job at making you feel like something is there, especially in a particularly tense section.

While The Backrooms turned into a bloated beast over time as more fans added pieces of lore to it, Anemoiapolis is finely homed in on the possibility that “something is out there.” Wandering these strange environments, things not adding up, your mind unable to quite lock down any sense of place is what makes Anemoiapolis so unsettling. Something could be around the corner, but that weighed against the opposite is where this deep-coded fear comes from.

What if there’s nothing there?

The endless halls, the twisted rooms and corridors, this stretching expanse of utter loneliness. There are no answers here. There is no solution, no salvation.

This is not for you.

Those are the words on the first proper page of House of Leaves, an incredible novel that deals heavily with a terrifying and oppressive liminal space, impossible geometry, and the extreme effects it has upon regular people. That’s the feeling here, this space that is very much not for you.

Exploring the Space Between

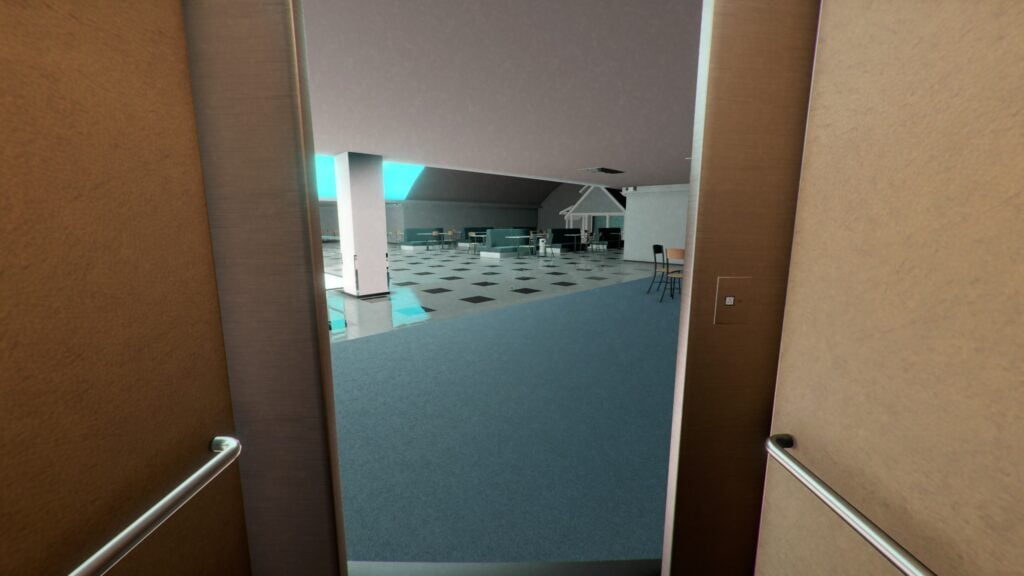

The core of Anemoiapolis is exploring these mind-bending places and diving into their uncanniness. Elevator tickets need to be collected to advance, and though this process is s a bit tedious, at least the tickets are plentiful. With a few unique environments each with their own little spins–as well as random generation building wholly unique layouts and ensuring the player is well and truly lost–the unsettling atmosphere is set up perfectly and keeps strong throughout the short playtime. Rounding a corner, turning back, and finding an entirely different room than the one you just left? *Chef’s kiss*

There is at least a little more depth than simply a walking sim in terms of mechanics. There are a few puzzles, albeit rather bare bones ones, mostly dealing with a circuit minigame. Striking a happy medium between authentic representation of kenopsia and liminal spaces along with keeping things engaging would be a difficult task, but thankfully the experience doesn’t overstay its welcome. A couple satisfying hours and the promise for more in following chapters is ideal. It does feel a little front-loaded on the puzzles, but I imagine as more chapters are developed we’ll get more interactions.

The visuals are on point, taking us through winding hotel hallways complete with bathroom fixtures, creepy indoor resort decorations, and floor after floor of movie theater carpet and blank posters. It’s like an uncanny valley but for structures rather than people. Anemoiapolis dips into the analogue horror aesthetic with a filter–the light fisheye–and captures the style of the 90’s in its locales. I must admit that the visual effects made me feel a bit ill after a while; sprinting through twisting corridors with the camera right out of a 90’s punk music video is disorienting to say the least. That being said, there’s options to fix all that with a few accessibility options for the visuals.

For anyone who’s a fan of liminal spaces, you’ll notice influence from a lot of the heavy hitter images. From the contrast in the green hills of a screensaver; to the brilliant Poolrooms inspired by the art of Jared Pike; to a take on the office hallways like those in The Backrooms. Even the shopping mall court that serves as your hub world has this back end of a house strangely positioned right near the tables, bringing to mind an image that blew up on Reddit a while back. Try to take a peak out of any windows you may come across–though they are very few and far between–and you might catch a glimpse of endless windows mirroring the strange look of a certain hotel’s courtyard.

However, some areas of Anemoiapolis are a lot more effective than others. There’s a lot of empty space. The office area is certainly unsettling, but it hasn’t got much substance. The mini-golf in the Country Club actually had me really excited; a liminal, procedurally generated mini-golf course with effectively endless levels? Sign me up! But in terms of gameplay, it’s very simple and loses its luster quite quickly. The area itself is just a vehicle for the golf as well, and makes for one you can quickly exit and skip over. As I said before, the balance of things is a difficult one, and it’s hard to keep someone’s attention and make them invested when the game relies on the player being invested at the get-go.

One area to highlight, however, which was also one of the earlier levels developed, is the Family Tropical Resort. That area does exactly what the others should do: have some sort of creative spin to things to offer both fantastic imagery and keep players captivated. At first, the only path forward is a lazy river that leads to a single bend and a little pool. It isn’t until you turn around that a labyrinth of turns has opened up. This section is a highlight, especially since you can take a ride down the fun little slides!

Overall, the atmosphere is admirable. There’s a soothing side to Anemoiapolis, a dichotomy that’s hard to explain. There’s this bubble of calm that comes from nostalgia, things you can recognize and remember. But the bubble is always on the verge of bursting, the empty corridors pressing in from all sides. Claustrophobia on top of autophobia.

In the end, this is an experience that’ll likely be appreciated by a select few. There’s honestly not much there, just wandering unsettling and yet intriguing environments. But for the most part, it’s done in a polished and effective way, and is a short horror experience that hints at enough of a deeper meaning to keep the players’ interest whilst leaning heavily on that feeling of true alienation. The endless halls, the twisted rooms and corridors, the stretching expanse of utter loneliness; there are no answers here. So you do the only thing you can.

Keep moving.

-

Features4 weeks ago

Features4 weeks agoThis Upcoming Romance Anime Might Just Break the Internet; Trailer Just Dropped!

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks agoDon’t Watch These 5 Fantasy Anime… Unless You Want to Be Obsessed

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks ago“Even if it’s used a little, it’s fine”: Demon Slayer Star Shrugs Off AI Threat

-

Culture2 weeks ago

Culture2 weeks agoMultiplayer Online Gaming Communities Connect Players Across International Borders

-

Game Reviews3 weeks ago

Game Reviews3 weeks agoHow Overcooked! 2 Made Ruining Friendships Fun

-

Features4 days ago

Features4 days agoBest Cross-Platform Games for PC, PS5, Xbox, and Switch

-

Guides4 weeks ago

Guides4 weeks agoMaking Gold in WoW: Smart, Steady, and Enjoyable

-

Game Reviews3 weeks ago

Game Reviews3 weeks agoHow Persona 5 Royal Critiques the Cult of Success

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks ago8 Video Games That Gradually Get Harder

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoDon’t Miss This: Tokyo Revengers’ ‘Three Titans’ Arc Is What Fans Have Waited For!

-

Game Reviews4 days ago

Game Reviews4 days agoFinal Fantasy VII Rebirth Review: A Worthy Successor?

-

Guides1 week ago

Guides1 week agoHow to buy games on Steam without a credit card