Features

‘Alice: Madness Returns’: Exactly as Lewis Carroll envisioned it

While inching through a steampunk-inspired maze, Alice Liddell fights off fork-wielding crockery while the Door Mouse and March Hare try to kill her with teapots projecting scorching liquid at her gothic-styled outfit. After many trials (and ‘Game Over’ screens), Alice finally finds the Mad Hatter, and it is at this point that the player realises that Lewis Carroll’s classic tea party has been somewhat spoiled, given that Hatter has been dismembered, and a torso cannot drink tea. American McGee’s idea of saving the Hatter is slightly more psychotic than in James Bobin’s portrayal of Alice Through the Looking Glass, mostly because of the deep and disturbing psychology that McGee incorporates into his not-so-child-friendly version of the classic children’s story.

Psychologically speaking, Alice: Madness Returns is fascinating in its dark interpretation of Carroll’s (seemingly innocent) book. Then again, he wrote about a young girl who goes to ‘a magical land in her head’, where she drinks special ‘potions’ that affect her size (or perception thereof), eats ‘mushrooms’ and then sings with flowers. And who can forget the hookah smoking caterpillar (who knows what’s in that hookah?), and the intermittent visibility of the Cheshire Cat? Whether Carroll intended it or not, Alice’s story sounds more like a schizophrenic girl on an LSD trip.

Alice: Madness Returns is a horrifyingly realistic interpretation of the questionable mental health of a young girl who witnessed her family burn to death, and was then blamed for it. Sent to Rutledge Asylum, an institution for the mentally insane, Alice is subjected to just about every unethical treatment in the psychoanalysis handbook, including trepanation (in which a piece of the skull is removed in order to ‘set the demons free’). It’s little wonder that Alice would invent a dissociative safe-haven to escape her disturbing reality. What makes the game truly brilliant is the exploration of mental illness and the way in which reality affects Alice’s Wonderland.

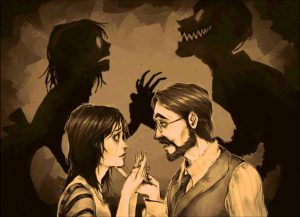

The basic premise of American McGee’s sequel is that Wonderland is being destroyed by an Infernal Train that is raging through Alice’s magical land and destroying it (Freudian psychology, anyone?). Interestingly, the train is modeled after a cathedral, thus, McGee uses symbolism to hint at what the truth is behind its appearance in Wonderland. Symbolism is a character of its own in Madness Returns, and the symbol of salvation being the very thing that is destroying Alice’s reprieve from a horrid reality allows for various interpretations. The train in question is operated by the primary antagonist, the Dollmaker. This once again opens up an entirely new world of disturbia, as Alice is forced to confront the horrors of her past in the form of monstrous dolls and other innocent objects twisted into dark and unsettling creatures. In fact, Alice’s twisted Wonderland is almost reminiscent of Silent Hill, in which every fear of those few who dare enter is personified into something extremely perturbing. Angela Orosco of Silent Hill 2 personifies her childhood abuse as the Abstract Daddy, a monster shaped as a bed holding two misshapen figures atop it. This concept is specifically pertinent with regards to the psychological experiences of Alice, as she too must fight personifications of a real-life abuser.

Luckily for Alice, while in Wonderland, she has the ‘power’ of Hysteria, a mode similar to Dante’s Devil Trigger in DmC: Devil May Cry, during which time slows down, Alice’s health roses are refilled, and she becomes incredibly strong. The irony is that up until the mid-20th century, hysteria was a one-size-fits-all diagnosis for women who basically couldn’t handle their shit. The treatment thereof was hysteria paroxysm; I’ll leave you to Google that. The implied sexism of a hysteria diagnosis is turned on its head in Madness Returns as it becomes a source of power, instead of a casual diagnosis for crazy women who just needed a little… paroxysm.

Meanwhile, in Victorian London, where Alice’s Wonderland is veering dangerously close to reality – to the point where she struggles to differentiate the two – Dr Bumby, Alice’s psychiatrist, hypnotizes Alice in order to better understand her mental escapism, to disastrous effect: escapism only works if what is eating at you in real life stays out of it. However, McGee yet again shows brilliant insight by illustrating how even the most elaborate escape, must, at some point, clash with reality. While walking the streets of London, Alice begins to see glimpses of her crumbling Wonderland – symbolic of a psychological breakthrough, in which both worlds become congruent and the truth of why the avoidance of reality is so vital to her existence becomes apparent.

Meanwhile, in Victorian London, where Alice’s Wonderland is veering dangerously close to reality – to the point where she struggles to differentiate the two – Dr Bumby, Alice’s psychiatrist, hypnotizes Alice in order to better understand her mental escapism, to disastrous effect: escapism only works if what is eating at you in real life stays out of it. However, McGee yet again shows brilliant insight by illustrating how even the most elaborate escape, must, at some point, clash with reality. While walking the streets of London, Alice begins to see glimpses of her crumbling Wonderland – symbolic of a psychological breakthrough, in which both worlds become congruent and the truth of why the avoidance of reality is so vital to her existence becomes apparent.

Alice: Madness Returns provides an unadulterated look into the human psyche, without being blatant about it. Symbolism and clever use of psychological concepts are constructed around a believable and (sadly) realistic portrayal of a damaged mind. American McGee tries, and succeeds, in illustrating escapism while answering questions most adults would ask about the dubious undercurrents of Lewis Carroll’s Alice series. Few people know that the man was more than just a writer of children’s stories: he was also a mathematician, logician, and an Anglican deacon (which partly explains the cathedral-themed train). He masterfully told the story of a troubled young girl under the guise of a fairy-tale and, having his own psychoses to deal with, provided a logical and cleverly concealed representation of the power of escapism.

I suppose the only question left to answer is: why is a raven like a writing desk?

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks agoDon’t Watch These 5 Fantasy Anime… Unless You Want to Be Obsessed

-

Culture3 weeks ago

Culture3 weeks agoMultiplayer Online Gaming Communities Connect Players Across International Borders

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks ago“Even if it’s used a little, it’s fine”: Demon Slayer Star Shrugs Off AI Threat

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoBest Cross-Platform Games for PC, PS5, Xbox, and Switch

-

Game Reviews3 weeks ago

Game Reviews3 weeks agoHow Overcooked! 2 Made Ruining Friendships Fun

-

Guides4 weeks ago

Guides4 weeks agoMaking Gold in WoW: Smart, Steady, and Enjoyable

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks ago8 Video Games That Gradually Get Harder

-

Game Reviews3 weeks ago

Game Reviews3 weeks agoHow Persona 5 Royal Critiques the Cult of Success

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks agoDon’t Miss This: Tokyo Revengers’ ‘Three Titans’ Arc Is What Fans Have Waited For!

-

Guides2 weeks ago

Guides2 weeks agoHow to buy games on Steam without a credit card

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoThe End Is Near! Demon Slayer’s Final Arc Trailer Hints at a Battle of Legends

-

Game Reviews1 week ago

Game Reviews1 week agoFinal Fantasy VII Rebirth Review: A Worthy Successor?