Features

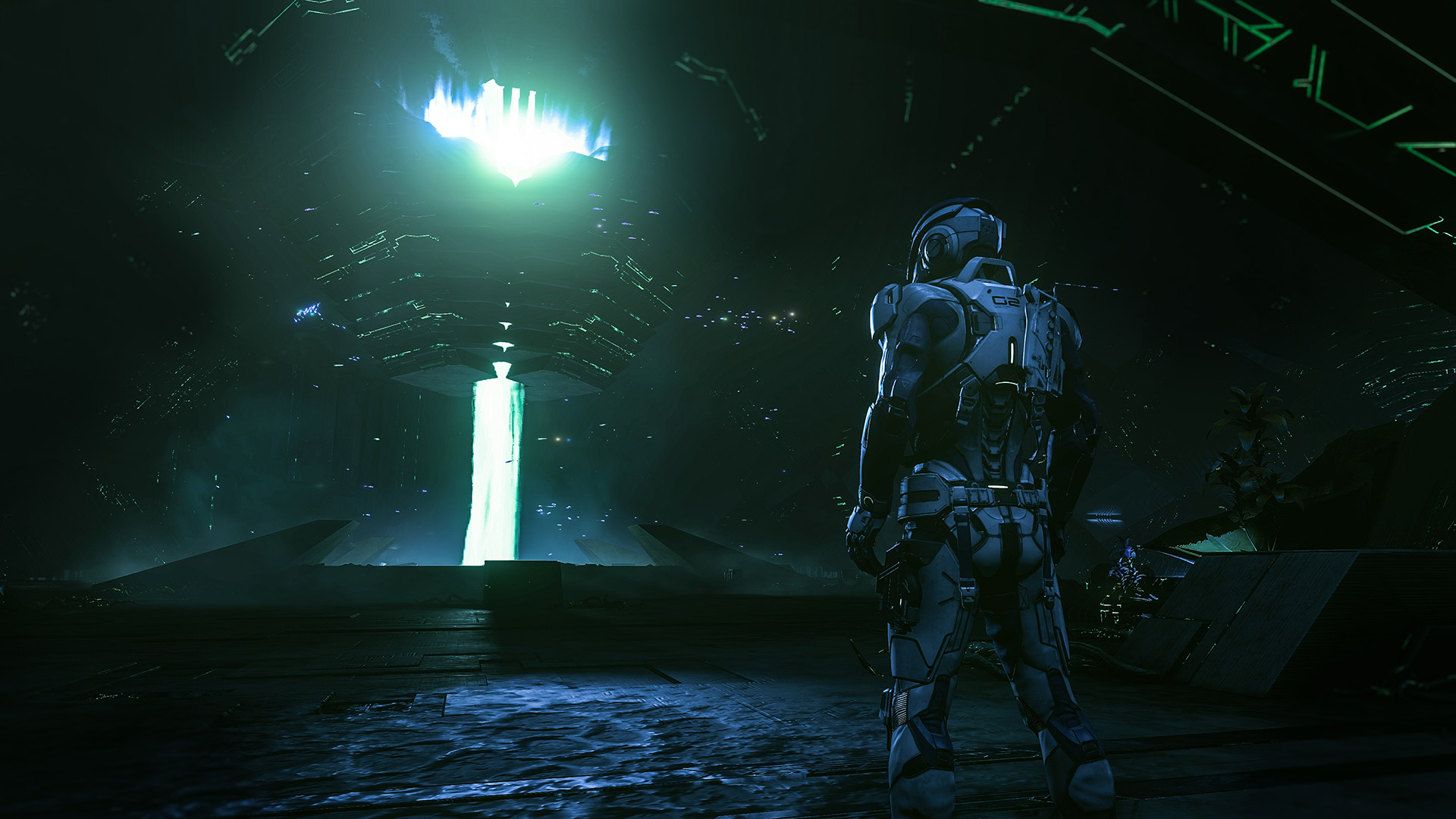

The Evolution of Free Will in Games: The DNA of Mass Effect: Andromeda

We are mere weeks away from exploring Andromeda in the latest Mass Effect entry. While the story, action, and sense of adventure drive many players to dive into Mass Effect, the series is also a prime example of player choice in triple-A gaming. Before setting off into the stars, lets take a look at the DNA of the Mass Effect series.

Choice in games is as old as gaming itself. As an interactive medium, choice was born when the first players chose to move their pixel left instead of right. Early games, like 1962’s Spacewar! ( Normandy prototype?), defined gaming as an active medium defined by choices, as opposed to passive mediums, like watching a film.

1985’s Super Mario, one of the games that started the modern era of gaming, lets players find secrets, and rewards exploration. Be it by items in hidden blocks, pipes that bring players to secret rooms, or warp tunnels, actions have repercussions on the game. However, these choices never really amounted to much, and while the journey may have been different, the end result was always the same (spoiler: you save the princess).

So now we complicate choice; players must be able to make decisions that not only tweak progression, but have meaningful repercussions and lead to different endings. Enter 1995’s Chrono Trigger, a game largely credited with popularizing non-linear gameplay. In this Square classic, the player not only has the option to play certain sequences in any order they choose, they can also skip segments all together, not in a “cheating” way, but as a legitimate choice. In the end, all of these options paid off with 13 possible endings.

In Mass Effect, decision-making is not limited to physical choices. Huge chunks of the game are taken up by dialogue, which adds another layer of complexity to the interactions within this world. Conversation in gaming finds its roots in the “dialogue tree.” As its name suggests, a dialogue tree is the blueprint of a branching conversation. As you make the choice to say one thing instead of another, certain conversational doors open, while others close. Dialogue trees predate video games, with the earliest exploration of them being in The Garden of Forking Paths by Jorge Luis Borges, a short story published in 1941. It examines a writer’s attempt to explore all possible outcomes of a given situation. For example, in one version of chapter 3, the protagonist dies, but in another, he lives on to chapter 4. The novel within the story is much like how the Mass Effect disc contains all possible outcomes of players’ choices.

This concept was popularized by “choose your own adventure” books, starting with 1976’s The Adventures of You on Sugar Cane Island, and eventually evolving into more complex RPG books. The first use of dialogue trees in computers was ELIZA, a 1966 project that simulated interacting with a therapist.

The precursor to modern western RPGs is undoubtedly tabletop RPGs, like Dungeons & Dragons, that were established in the 1970s. These games find their roots in improv theater, war games (more elaborate forms of chess), and communal storytelling that dates back centuries. Tabletop RPGs have dialogue and actions that can lead in any number of directions, with stats attempting to keep the adventure driven and focused.

Dialogue trees were therefore essential in bringing pen-and-paper RPGs to video game form. Classic CRPGs attempted to imitate the boundless nature of tabletop role-playing games by using extensive, far-reaching dialogue trees. One of the most beloved CRPGs, 1998’s Baldur’s Gate, was even based on the most popular pen-and-paper RPG of all time: Dungeons & Dragons. Coming full circle, Baldur’s Gate was created by a then-fledgling studio known as Bioware, the masters of Mass Effect. Before creating the star-faring series, the studio made Neverwinter Nights, another Dungeons & Dragons game, and a sequel to Baldur’s Gate.

Mass Effect and other modern RPGs have deep roots not only in video game history but also in human history. The desire to live another life outside the limitations of our own has fueled imaginations for generations. We are weeks away from the release of what is likely to be the most fully realized fantasy adventure beyond our universe ever put in human hands, and when you put it that way, I, for one, am excited.

-

Features4 weeks ago

Features4 weeks agoDon’t Watch These 5 Fantasy Anime… Unless You Want to Be Obsessed

-

Culture3 weeks ago

Culture3 weeks agoMultiplayer Online Gaming Communities Connect Players Across International Borders

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks ago“Even if it’s used a little, it’s fine”: Demon Slayer Star Shrugs Off AI Threat

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoBest Cross-Platform Games for PC, PS5, Xbox, and Switch

-

Game Reviews4 weeks ago

Game Reviews4 weeks agoHow Overcooked! 2 Made Ruining Friendships Fun

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks ago8 Video Games That Gradually Get Harder

-

Game Reviews4 weeks ago

Game Reviews4 weeks agoHow Persona 5 Royal Critiques the Cult of Success

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks agoDon’t Miss This: Tokyo Revengers’ ‘Three Titans’ Arc Is What Fans Have Waited For!

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoThe End Is Near! Demon Slayer’s Final Arc Trailer Hints at a Battle of Legends

-

Guides2 weeks ago

Guides2 weeks agoHow to buy games on Steam without a credit card

-

Uncategorized3 weeks ago

Uncategorized3 weeks agoSleep Meditation Music: The Key to Unwinding

-

Game Reviews1 week ago

Game Reviews1 week agoFinal Fantasy VII Rebirth Review: A Worthy Successor?