Features

‘Detroit: Become Human’: Exploitative and Tasteless

Like any David Cage game, Detroit: Become Human tells a story that is ambitious, ridiculous, and doesn’t shy away from difficult content. The game takes place in a dystopic future Detroit where androids have become a part of everyday life: they live as bodyguards, nannies, maids, and sex-workers, and are treated as non-human property. That is until the androids begin to gain consciousness, and we follow the lives of three of these deviants: Connor, Kara, and Markus, as they struggle for freedom.

There’s a lot to be said for Detroit as a game: its environments and level design verge on the cinematic, its narrative choices make the world feel both expansive and meaningful, and the actors involved deserve real credit for an incredible array of moving performances. However, the story that Detroit tells is exploitative, it is tasteless, and it is unimaginative. It is challenging in every way, save for the philosophical. For the most part, Detroit’s “ambitious” scenes rely on shocking content that forces an emotional reaction, taking advantage of themes such as child abuse or the Holocaust without gravitas, respect, or due consideration.

You can read our full review of Detroit: Become Human for an impartial look at the game that fairly considers gameplay and mechanical elements. But this opinion piece looks to provide a critique Detroit’s more questionable story decisions, and the scenes which undermine the game’s argument and vision – because frankly, Detroit doesn’t deserve praise for exploiting stories of abuse and genocide for a game that only goes skin-deep.

-

Exploiting Child Abuse and Player Emotions

We knew right from the start that Detroit: Become Human was going to be heavy going. The 2016 and 2017 trailers both featured children in peril: first a child dangled from a rooftop, then a young girl being beaten by her father, but David Cage defended the dark subject matter with the promise that “there’s a context in the story, there’s a reason for that”, and we gave the game the benefit of the doubt. The problem is that having now seen the game in full it is clear that Cage’s child abuse narrative isn’t content with just one scene, and definitely isn’t used with care, context, and solid reasoning.

Todd beating his daughter, Alice, as Kara looks on helplessly is the main drive in Kara and Alice’s storyline. The horrific scene allows Kara to break through her programming, and follow the maternal instinct to protect Alice through the rest of the game, but beyond this convenient plot point, there isn’t much in the way of context to justify Alice’s constant exposure to violence, isolation, and threats of pedophilia.

Is there a context to help us understand Todd’s actions? He’s poor, overweight, he uses drugs, and his wife recently left him. If that sounds like a stereotypical ‘bad’ character backstory, that’s because it is. Alice doesn’t do anything to provoke Todd’s violence, in fact, she doesn’t say anything as the script escalates Todd from angry muttering to flipping the table and hurling abuse at his child. It would be laughable how the writing magics child abuse out of nowhere just to satisfy some dramatic tension in a scene – if it weren’t so horrific.

Of course, this isn’t an argument that games should never use violence or show complex situations. As an art form games are uniquely capable of helping us to explore such painful topics and resolve our feelings around them, to empathize, understand, and feel moved to action. Detroit: Become Human simply doesn’t do that. Instead, it revels in your feeling of anger, confusion, and helplessness, it exploits your emotions by shoving a child on screen and beating her as an easy plot device.

Even your final vindication of breaking free, and perhaps even murdering the abuser, is a brief-lived freedom because Kara’s story literally doesn’t develop any further. Her entire storyline is looking after Alice, running from strangers, policemen, and threats of child molestation (Sorry, Jerry). The game even puts you through a concentration camp with Alice, separates you, and threatens that she could be exterminated.

It doesn’t help that Alice’s script comprises some of the most desperately clichéd Disney-sweet lines possible: “Why didn’t he ever love me?” “All I wanted was a life like other girls, maybe I did something wrong?” “Maybe I wasn’t good enough. That’s why he was always so angry.” “I just wanted him to love me. Why couldn’t we just be happy?” – I’m sorry, Alice, it’s because David Cage thinks being abused is a great plot device. The problem is these lines are so senselessly over-dramatic that much of the effect is lost – at least in my case, I couldn’t take the hyperbolic handling of Alice’s abuse seriously. It was staged precisely to manipulate the viewer, and it was sickening in its laziness.

Perhaps Cage’s reasoning lies in the fact that towards the very end of the game we discover that Alice was an android all along. Perhaps this is supposed to make us wonder whether it was ok for Todd to beat her, for Zlatko to turn her into a slave, or for the concentration camps to exterminate her. I’m afraid that whether concentration camps are good or not is a moral quandary far too deep for me to answer, so I’ll stick with pointing out that whether the child is an android or not, the child abuse that Detroit depicts takes advantage of its players, and uses a deeply serious subject utterly without care. The bottom line is if you want to feature child abuse in your game, it should be done with delicacy, and respect, not as a shoddy covering of a lack of character development and a quick recipe for some emotional drama.

-

Concentration Camps and Civil Rights as Political Allegory

While you might agree Detroit’s use of child abuse goes too far, there are other issues with how it uses political allegory. The game’s core philosophy is the question of whether androids should be accepted as human: with thoughts, feelings, and rights of their own. In David Cage’s world, androids do not have rights, nor are they even recognized as having personhood or consciousness.

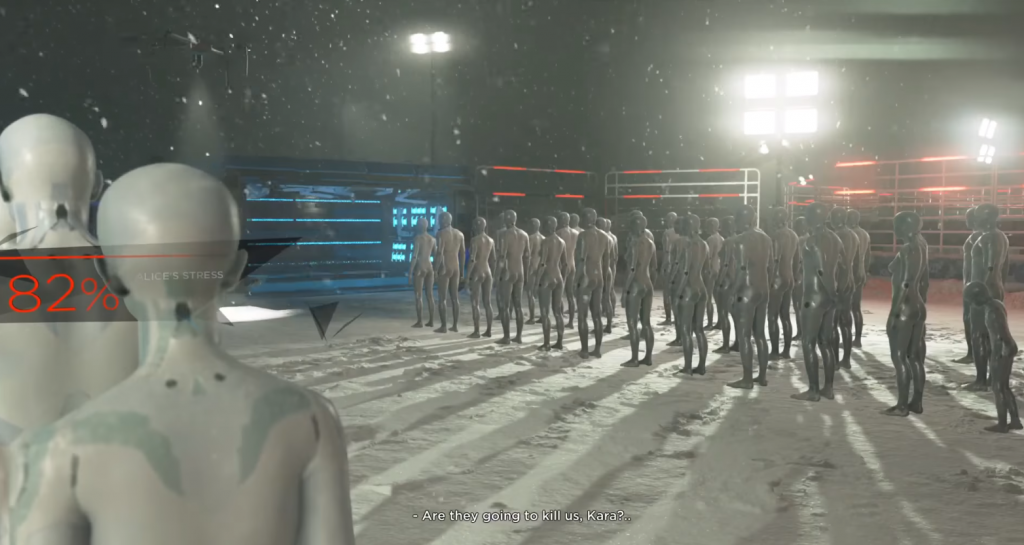

Androids cannot disobey, and the only consequence of harming one is a possible insurance fee for damaging someone’s property. Androids are referred to as ‘it’, they are banned from bars and public spaces alongside ‘No Dogs’ signs. Androids are marked with blue triangles and an armband that must be visible at all times. They are literally rounded up and sent to concentration camps, stripped, separated, and shot.

Clearly, there is an allegory here to the slave trade and civil rights movement, and boy does Detroit highlight it. From black characters literally explaining their sympathy for androids through the similarities of their past treatment, to using ‘We have a dream’ and the black power symbol as slogans in the android uprising, Detroit: Become Human is not afraid to draw parallels between real periods of discrimination and genocide in our history, ones which we still feel the presence of today, and the very important android uprising taking place in this game.

Perhaps these historical references help players empathize, not just with the story of the androids, but also with those of other races and creeds. Perhaps it helps players to understand the struggles of others and the horrors of the past. But does it not also destroy any moral complexity to the android’s right to freedom? Literally aligning the actions of the humans with Hitler cancels out Detroit: Become Human’s most interesting question as to the android’s right to freedom.

Obviously, androids are human and deserve their own rights, to disagree is to side with the Nazis, KKK, and child abusers all in one. Even if you think Detroit: Become Human has every right to use these sensitive political references with all the subtlety of a rampaging elephant, you might agree that Detroit’s handling of them destroys any question of what is morally right or wrong in this situation.

How far this use of traumatic historical events is a problem for you is ultimately a matter of taste. Historical events are not sacred – to be left untouched and unquestioned, and drawing parallels to them in works of art can create a powerful commentary and connect to a new audience. But in my opinion, Detroit goes too far: it rubs your face in too many obvious references, salts too many open wounds, and above all borrows from a history which it has not earnt the right to use.

Detroit: Become Human is not solemn, it is not complex, it is not thoughtful in its use of allegory. A story that wants to highlight the horrors of Hitler’s concentration camps, the struggles of the civil rights movement, racism, segregation, and the terror of experiencing child abuse – should not also include rain-drenched lesbian sex robots fighting in underwear and heels.

-

Fetishizing Torture and Demeaning Women

Detroit: Become Human’s “philosophically challenging” content is made unforgivable when we look at the game’s use of women. It falls into the skin-crawling category of obsessive power fantasies: both of the male controlling and torturing captured women, and of overtly sexualized yet domineering women who are beyond the need for men (but let’s enjoy looking at them anyway).

The former occurs as Kara and Alice are captured and tied up by a perverted android serial-killer, and potential pedophile, who attempts to wipe Kara’s mind and turn her into the perfect slave. His house is filled with the disfigured and sexualized bodies of previously captured androids, one male android left sitting in a bathtub with only a head and torso remaining screams excitedly that you “must obey master” as you flee past. As your memory is drained away Alice is shoved to the ground as the abuser tells her “I’m going to teach you some manners you little bitch”, and held captive for the pervert’s own fancies, whatever they may be.

In all fairness, this scene can play out in multiple ways, and some might not seem like such full-on BDSM psycho torture scenes as others. In case you missed the highlights, you can find tortured androids in the basement who tell you “He likes to play with us”, and a burnt out female droid on her knees in the corner of Zlatko’s bedroom, wearing nothing but panties. If you fail to regain your memories, you can literally stay as Zlatko’s slave for the rest of the game, with Alice dragged away to a black screen. Let’s take a moment to appreciate this quote:

“The rule I give myself is to never glorify violence, to never do anything gratuitous. It has to have a purpose, have a meaning, and create something that is hopefully meaningful for people.” – David Cage

Is Zlatko’s torture mansion not gratuitous? Is it serving a purpose? I would argue that this torture fantasy comes out of nowhere. It makes no fine points about the nature of humanity, and it has no connection with Detroit: Become Human’s or Kara’s greater story. At most, it adds a side-character we can take along with us. Was it necessary to show the monstrosity of abuse performed upon androids? Was it necessary to beat Alice again? At best, this scene once again exploits child abuse and sexualized torture for the sake of ‘intense’ drama. At worst, this scene is meant to titillate.

In a separate scene, we see a reverse “forward-thinking” and “empowering” view of women. As Connor, we are tasked with the daunting video game trope of having to enter a strip club, examining another case of deviant android activity. What we uncover, after a dutiful investigation of every possible angle at the strip club, is a murderous female android, skin shimmering in the falling rain, beautiful and fearsome as she flings herself against us, determined to fight in nothing but her bra and stiletto heels.

Yet her empowerment is realized yet more as we discover that not only is she sexily rebelling against her rape and abuse as a sexbot, but also that she is in love with her fellow oiled up naked colleague. The revelation that these strippers are not only independent sexy women but are also, in fact, lesbian lovers, is almost too ground-breaking to bear. What an incredible romance story. What a novel idea. What a convenient excuse to spend hours modeling softcore pornography. If you’re not picking up on the sarcasm in this paragraph, you might have the perfect reading level to appreciate this scene.

As if it wasn’t enough, Detroit: Become Human’s voyeuristic sexualization of women is not just an uncomfortable addition to an otherwise philosophically sound venture. Detroit fundamentally does not understand what it is doing. How? With its menu screen.

Detroit: Become Human uses a female android, Chloe, as your own personal menu navigator. She speaks to you, adjusts your settings, gives you advice, and- crucially, can be set free at the end of the game. The idea is that the player, by the end of Detroit: Become Human, might well feel uncomfortable with their own use of Chloe as a personal android. She’s chained to the menu screen, forced to serve your whims, and eventually, she decides to ask you to let her leave.

It’s a neat metanarrative touch, and it would remain so, if not for the fact that Quantic Dream tweeted recently that due to popular demand they’ll be returning Chloe to the menu screen. You’ll be able to “acquire a brand new model (but your original Chloe will still be free)”. So, never mind about android freedom, we understand that you miss your blonde menu-screen pet, we’ll return her but say it’s a new model so you can feel ok about it. It’s impressive how a game can manage to so fundamentally misunderstand its own premise.

Detroit: Become Human is an impressive game. It is beautiful and ambitious, and despite its failings, it has unquestionably had an effect on many players. It is right that games should strive to address complex subject matter, and leave their impact on the political landscape. But in my opinion, Detroit loses all credibility with its thoughtless script, its careless depiction of child abuse and genocide, and its decision to feature demeaning sexual fantasies under the guise of progressive fiction.

It is easy to be swept up in the glamour of Detroit, but its story is ultimately cheap. If Cage wants to champion video games as an art form, and espouse complex gameplay mechanics in favor of a pure script punctuated with quick time events, then it stands to reason that the story be critiqued closely. Sadly, for all its efforts, Detroit: Become Human ends with a story that is emotionally, politically, and sexually exploitative. These themes deserve better.

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks agoDon’t Watch These 5 Fantasy Anime… Unless You Want to Be Obsessed

-

Culture3 weeks ago

Culture3 weeks agoMultiplayer Online Gaming Communities Connect Players Across International Borders

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks ago“Even if it’s used a little, it’s fine”: Demon Slayer Star Shrugs Off AI Threat

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoBest Cross-Platform Games for PC, PS5, Xbox, and Switch

-

Game Reviews3 weeks ago

Game Reviews3 weeks agoHow Overcooked! 2 Made Ruining Friendships Fun

-

Guides4 weeks ago

Guides4 weeks agoMaking Gold in WoW: Smart, Steady, and Enjoyable

-

Game Reviews3 weeks ago

Game Reviews3 weeks agoHow Persona 5 Royal Critiques the Cult of Success

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks ago8 Video Games That Gradually Get Harder

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoThe End Is Near! Demon Slayer’s Final Arc Trailer Hints at a Battle of Legends

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks agoDon’t Miss This: Tokyo Revengers’ ‘Three Titans’ Arc Is What Fans Have Waited For!

-

Guides2 weeks ago

Guides2 weeks agoHow to buy games on Steam without a credit card

-

Game Reviews1 week ago

Game Reviews1 week agoFinal Fantasy VII Rebirth Review: A Worthy Successor?