Features

Where Are all of the Slice-of-Life Video Games?

Slice-of-life stories are everywhere, it seems. The vast majority of all sitcoms, 4-panel comics, romance and comedy TV shows, are just that. So are lots of books and anime, to not say anything about reality TV and IRL livestreams. We seem to be enamoured by the idea that a piece of media could show us life as it is, especially when that piece of media has all the talent and money behind it as a Netflix original. And while the obsession with realism that dominates the current media landscape goes far beyond this one genre, it is undeniable how much the popularity of the slice-of-life story has influenced modern storytelling.

With the exception of games, that is.

Looking for slice-of-life videogames, you won’t find more than a handful that many can recognize. A few, the most popular of the bunch, are going to be either work simulators, such as the farm-life sims Harvest Moon and Stardew Valley, or regular-life sims, like Animal Crossing and the conveniently named The Sims. Meanwhile, the vast, vast majority of the games in this list are going to be visual novels.

The reason for this might seem obvious: slice-of-life stories, to their core, are about comedy, romance, or interpersonal drama – all stuff that few popular games have in heaps, and even fewer are actually built upon. But just as with every norm, and just as important as that norm, here lies a crucial exception. In fact, there are several exceptions, and their name is Adventure Games: Sayonara Wild Hearts is a wild Music Video/Arcade Game hybrid where you help a girl rebuild her broken heart; Kentucky Route Zero is about how we choose our pact trough life, explored with magical realism; the “Ben and Dan” series, of Ben There, Dan That! fame, is all about telling tongue-in-cheek jokes and toying with the tropes of point and click adventures. Our three core components, romance, drama, and comedy, are all here, yet none of those games could be called slice-of-life. Meanwhile, you’d be hard press to find a single dating sim that isn’t a slice-of-life.

Stories this mundane really seem to be incompatible with a certain “game-ness” that visual novels, simulators, and interactive fiction often don’t have quite as much of: compared to even the most down to earth action games, like the miserably accurate medieval life sim Kingdom Come: Deliverance, visual novels have much more dialogue, more characters to develop a relationship with, more letting your mind wander over what you’ll do next weekend, passing time before your work day is over. It’s not that video games don’t want to be slice-of-life, or that they don’t want to be relatable. They just don’t want to run the risk of looking mundane, of not appearing like a videogame should.

Not many know that the term “slice-of-life” comes from the French “tranche de vie”, originally coined to describe the way the stage of Antoine’s Living Theatre was set up during their naturalist plays. Antoine would build the scenography for a stable by bringing chickens and hay on the stage; he would insist that the public feel the warmth of the bakery’s oven, and smell the rotting flesh hanging from the ceiling of the abattoir. Unsurprisingly, opposition came quickly, with many believing that this style was not just unpractical, but fundamentally incapable of capturing the depth of modern life, its deep and delicate essence lost in a sea of details. Symbolists writers, like the poet Maeterlinck, argued that this inner life would be better expressed through dialogue without actions, through the poetics of “depth and stillness”, and without a real stage preparation, letting the public paint their own picture of the world after hearing the actors’ words.

The relation between XIX century French theatre and the modern slice-of-life might be indirect at best, bet there is at least one major point of connection between the two: they both aim to be meaningful while remaining mundane, elevating the tiny ups and downs of normal routine to the exceptional level of importance that one would instinctively give them, had they experienced them in actual daily life. We see this in the recent Visual Novel/Dating Sim My Sweet Zombie!, from Tsundere Studios, where the dramatic contrast between the fear and the excitement inherent to building a new relationship is exaggerated by the discovery that your new friend and housemate is an actual zombie.

Although it is slight, there is an inconsistency in what we just saw: within videogames, the slice-of-life remains in the domain of visual novels, a genre whose defining characteristic (and most criticized aspect) is an (over)reliance on text. For the most part, this text is dialogue spoken by the characters, either in conversation or as a monologue, and it is often delivered through static character art that is sitting on a static background. Just like in actual novels, and in some styles of theatre, it’s the audience’s job to combine those different elements into a cohesive whole: to give the characters a real voice and to see them looking at each other, not staring motionless at the player but freely moving and acting together. Given what we know, Visual Novels should be a terrible fit for slice-of-life stories, especially when compared to the fully explorable environments of open world games. But those aren’t perfect either: their problem, as explored before, is instead an unwillingness to show and elevate daily life, and there can’t be a slice of life without daily life.

Let’s imagine, though, what sort of game we would need to find that digital simulation of life. First, we’re not talking about the small, relaxed life of Animal Crossing, or the unwilling parody of the American suburbs that is The Sims, but of realistic, over-detailed replicas of life, maybe a bit exaggerated in some aspects, in videogame form. We’re not talking about MMORPGs or virtual worlds like Second Life either. This last one, in particular, explains it all, right in its name: virtual spaces don’t try to represent life in a digital environment, they create the space for another one, a Second Life, to exist beside the first. And just living is certainly not the same as performing slice-of-life.

One peculiarity of Antoine’s Living Theatre, one that initially doesn’t seem to fit well with the positivist, naturalist attitude of the theatre, is that actors, there, would often improvise their lines, and could freely speak with the public. The reason for this was that life, at the Living Theatre, wasn’t represented in the story the actors played, or conjured up in the minds of the public: a piece of life, the tranche de vie, was instead mounted on the stage itself. As such, a strong connection between the replica of life, the actors and their stage, and the public, which could leave the theatre and remain alive, would have allowed the false life of the play to come alive through the audience.

But like with the original critics of naturalism, after thinking that we could bring to life, at least on a screen, whichever event, activity, or human experience we know enough about, we started to realize that this, too, does not make life. For one, life is a story. It is internal and introspective. To see life through someone else’s eyes, or to see their environment brought to the stage with them, means nothing if we don’t know whose eyes those are and if it isn’t them that tell their story.

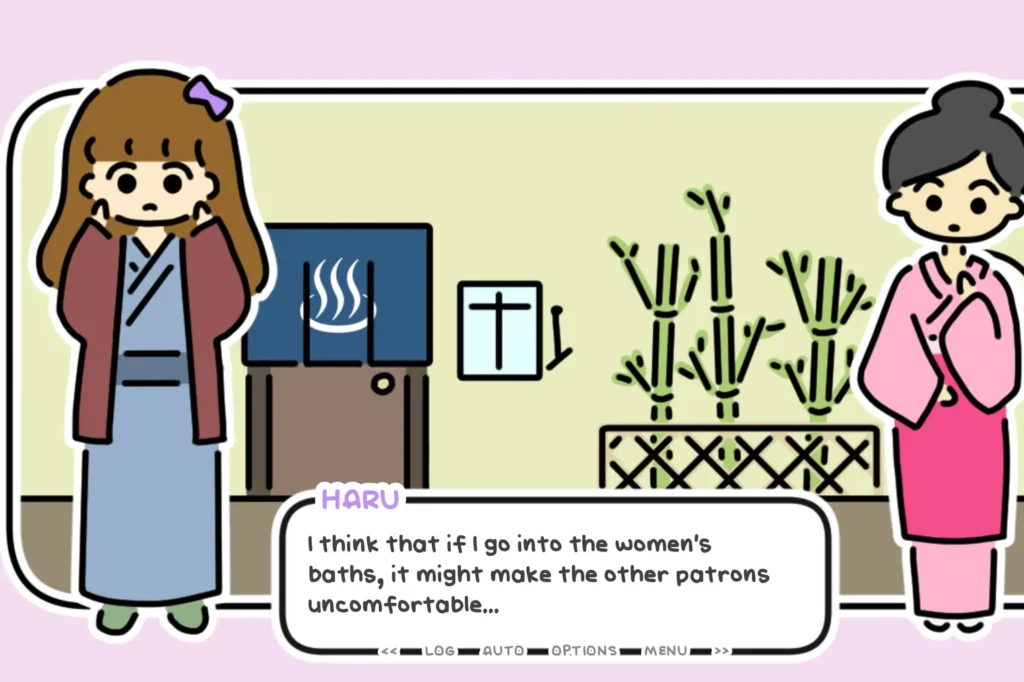

In One Night, Hot Springs, a short Visual Novel from solo developer “npckc”, the environment is only present to allow the protagonist to find her place within it, and to bring conflict between her and her friends. The same could be said for the plot: when this story is reduced to the main story beats, it barely feels like a story at all. One Night, Hot Springs is, in short, the story of three friends who decide to go to a Japanese hot spring. They talk, they bathe, they sleep, and the next day, they leave. That is what happens in this story, but from that description alone you can’t tell what the game is about at all.

That is because much more importance is put on the protagonist’s perspective, on her own experience of the story and on what makes this her story. What I haven’t told you is that Haru is a trans woman and that one of the friends she’s going to the hot springs with does not know that, and that Haru doesn’t know how this other girl will react. She doesn’t simply act as a reaction to her environment, and her action alone does not make her story. The internal drama contained within her own self, and the ability of visual novels to convey her inner life, are what makes this mundanity feel meaningful and insightful – what makes this story feel like a slice of her life.

Antoine created, for its stage, precise recreations of real locations because his positivist upbringing brought him to believe that the actions of any one person were driven by their environment, which then had to be brought on stage as part of the characters themselves. But there is much more to what moves us than the material world surrounding us, something that most games are ill-equipped to deal with. Visual Novels are a great fit because they rely heavily on dialogue, letting the characters themselves express their story, because they can skip the boring part of life without wishing it away, and because they allow the player to build their own picture of this world. Doing this, they are able to explore this “depth and stillness” of modern life in its mundanity.

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks agoDon’t Watch These 5 Fantasy Anime… Unless You Want to Be Obsessed

-

Features3 weeks ago

Features3 weeks ago“Even if it’s used a little, it’s fine”: Demon Slayer Star Shrugs Off AI Threat

-

Culture3 weeks ago

Culture3 weeks agoMultiplayer Online Gaming Communities Connect Players Across International Borders

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoBest Cross-Platform Games for PC, PS5, Xbox, and Switch

-

Game Reviews3 weeks ago

Game Reviews3 weeks agoHow Overcooked! 2 Made Ruining Friendships Fun

-

Guides4 weeks ago

Guides4 weeks agoMaking Gold in WoW: Smart, Steady, and Enjoyable

-

Game Reviews3 weeks ago

Game Reviews3 weeks agoHow Persona 5 Royal Critiques the Cult of Success

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks ago8 Video Games That Gradually Get Harder

-

Features2 weeks ago

Features2 weeks agoDon’t Miss This: Tokyo Revengers’ ‘Three Titans’ Arc Is What Fans Have Waited For!

-

Features1 week ago

Features1 week agoThe End Is Near! Demon Slayer’s Final Arc Trailer Hints at a Battle of Legends

-

Guides2 weeks ago

Guides2 weeks agoHow to buy games on Steam without a credit card

-

Game Reviews1 week ago

Game Reviews1 week agoFinal Fantasy VII Rebirth Review: A Worthy Successor?